Amy Sherald: Living in America

“Success, for me, is staying true to who you are and not deviating off a path.”

Amy Sherald’s striking, visually arresting portraits capture the indefinable spirit of contemporary America. Since painting Michelle Obama’s portrait in 2018, the press were quick to portray her as an overnight success, but this undermines the strength, determination and years of hard work that led her to international fame. “I had a career before Michelle Obama,” she bites back. Challenging notions of racial prejudice and stereotyping, her iconic images invite viewers to see the whole person, beyond nationality or the colour of their skin. She carefully selects people to paint with an indefinable factor x that she can bring out through the process of making, writing: “It’s hard for me to find people to paint. There has got to be something about them that only I can see.”

Born in Columbus, Georgia, Sherald was one of only a small number of black students at her private school. Describing herself as an “introvert,” it was the school’s art classes that drew her in, allowing her to be amongst other people without having to engage directly, explaining, “Art class was my safe haven.” As a young, aspiring artist Sherald struggled to find role models, but the first black artist she encountered was Bo Bartlett, whose work she saw during a sixth grade school trip and she never forgot the experience, remembering, “It really resonated with me, because I had never seen a painting of a black person before.”

Amy Sherald at her Baltimore, Maryland studio with her dog August by Justin T. Gellerson for The New York Times

Sherald’s father was a dentist and her family hoped she, too, would follow in the medical field, but it was not to be. Instead she chose to study fine art, first with an undergraduate at Clark-Atlanta University, where her tutor Dr. Arturo Lindsay “pushed me into becoming the person that I wanted to become.” After completing her studies she headed to Maryland Institute College of Art for a masters and her natural inclination towards portraiture became solely focussed on black people. Studying the field of American Realism, she became fascinated by paintings of people in everyday tasks and set out to create the same sense of the ordinary and familiar in her own work.

Freeing Herself Was One Thing, Taking Ownership of that Freed Self Was Another / Amy Sherald / 2015 / Oil on canvas

Not long after graduating from Maryland, Sherald’s underlying health issues first came to her attention. After visiting a doctor while training for a triathlon in 2004, she was diagnosed with a cardiomyopathy, and told she may need to have a heart transplant in the next few years. Struggling to make ends meet, Sherald waited tables to pay for her medical treatment, all the while continuing to try and make paintings. Health issues ran across her family as her brother Michael was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer, and her mother and two aunts fell ill, often leaving her in the position of carer.

In 2012, Sherald collapsed inside a Rite Aid store and blacked out. When she came to in hospital and was told she would have to have a heart transplant, the gravity of her situation became clear, as she recalled, “I felt like I could die then … I actually felt that for the first time, and it did scare me. I thought, ‘I can’t be afraid to die’, so I just made peace with it at that moment. I said, ‘I’m not going to be afraid, it’s all going to be okay.’” While in hospital waiting for a heart donor, she found out her brother had died of cancer.

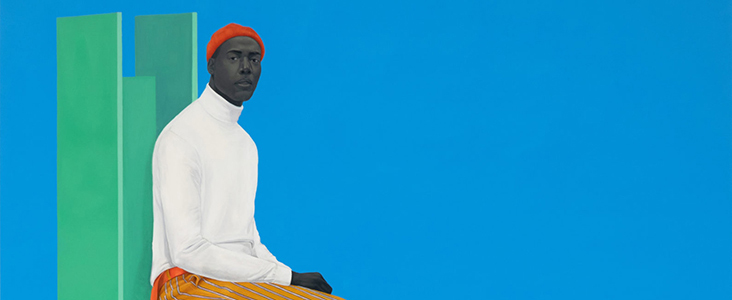

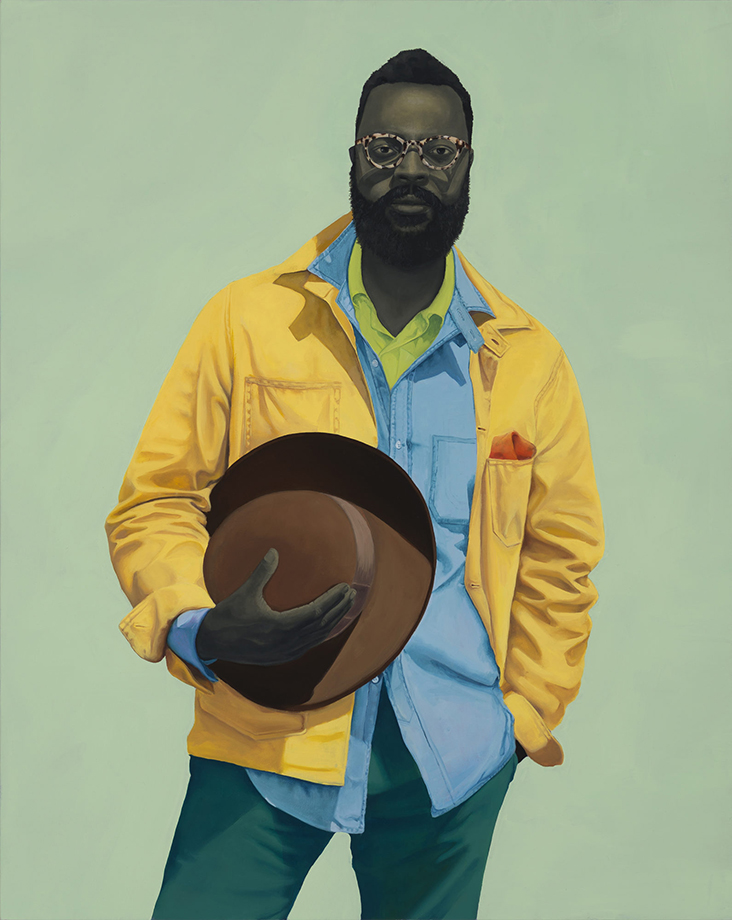

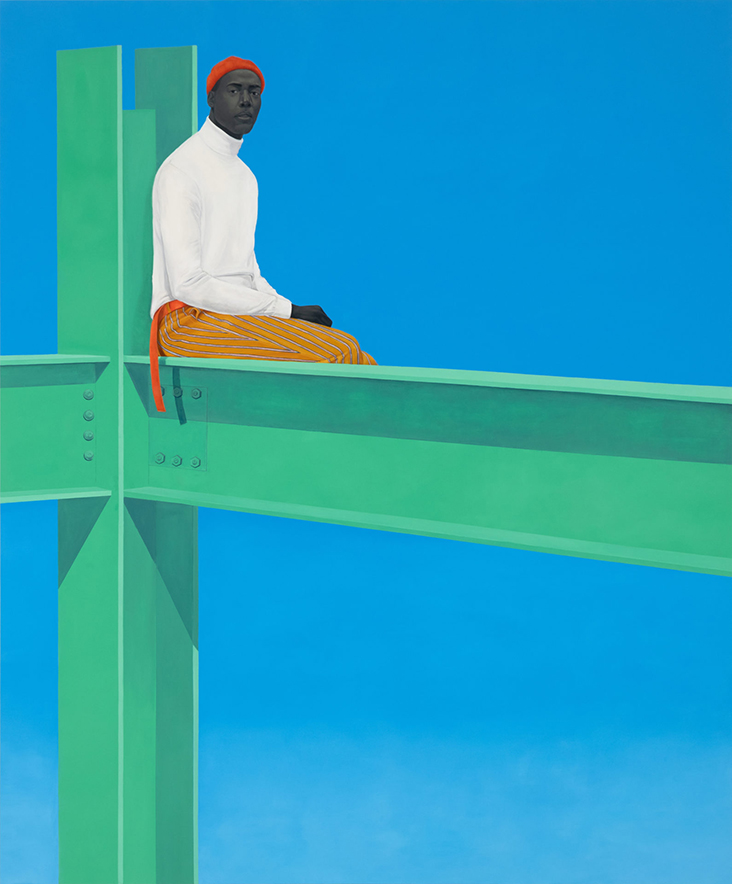

Sherald survived her transplant operation, although it took her nearly a year before she could resume painting again. Slowly, the work that unravelled out her near-death experience was portraiture. Depicting African-American people from all walks of life, Sherald’s images were quickly recognised and appreciated for their fresh candour, encapsulating the individual spirits of her subjects, as seen in works such as Pythagore, 2016, Freeing Herself Was One Thing, Taking Ownership of that Freed Self was Another, 2015, and What’s Different about Alice I that She Has the Most Incisive Way of Telling the Truth, 2017. Happenstance led her to discover the power of leaving her models’ skin tone grey, as she explained in an interview, “I had started a painting, and I was going to do glazes of brown over the grey. But then I decided not to, because it looked beautiful the way that it was. The commentary and the discourse, that comes afterwards; it wasn’t in my head at the time.”

The discourse she refers to became one of the key talking points of her art, which upturned pre-conceived ideas about “colour-as-race” and allowed for, as writer Wesley Morris puts it, “blackness without the gaze of whiteness.” Sherald also links her fascination with grayscale to her love of black and white photography, particularly her own family’s archive, which captures figures “frozen in time, and black and white, and they’re so still, and their eyes tell you so much.” The artist has often been praised for investing this same emotional intensity into the eyes of her own subjects, who seem to live, breathe and feel in the space around them.

What’s different about Alice is that she has the most incisive way of telling the truth / Amy Sherald / 2017 / Oil on canvas

Steadily Sherald’s reputation was growing and in 2016 she was awarded first prize in the Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition for the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C., which earned her a substantial cash sum and a wide amount of press attention, as the gallery’s associate curator commented at the time, “She’s starting to get the recognition she deserves.”

Michelle LaVaughn Robinson Obama / Amy Sherald / 2018 / Courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The following year Sherald’s work hit headlines again when she was chosen to paint her famous portrait of the former first lady Michelle Obama for the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery; the work was praised as much for its Renaissance composition as Obama’s engaged, confident, yet introspective expression, reflecting the complex and sensitive intelligence of her subject. Sherald spoke of the first lady’s approachable nature, which made tackling the portrait of such a prominent public figure that much easier, saying in an interview, “She’s very authentic so it kind of takes away any feeling of nervousness because she doesn’t come into situations like ‘I’m the Former First Lady.” It’s just like Hey, y’all…” When Sherald’s portrait of Obama, titled Michelle LaVaghn Robinson Obama, 2018, was unveiled, the image went viral, attracting a huge internet following, while visitors to the museum shot up by 300 percent. Since then, Sherald has amassed an enormous public following that far exceeded her expectations, with a dramatic number of letters coming her way and even a few fans trying to hunt down her home.

In the same year, Sherald won the 2018 David C. Driskell Prize from the High Museum Art in Atlanta and has, since then continued to exhibit widely across the United States. Major solo and group exhibitions have followed in sites including Miami, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and North Carolina. Perhaps most importantly for Sherald, though, is having her work on display in large scale museums, not just because it lends her work a greater sense of weight and gravitas, but also as she is able to become a role model for a new generation, providing a cultural reference to African-American society that was so hard for her to find when she was growing up. She comments, “Kids know who I am now, which is really exciting. They’re learning in art class about portraiture through my portraiture, which is special, because I had to learn about portraiture through European painting … Kids can look at my work and see somebody who looks like them and be empowered by that.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

What a strong woman. Her paintings are so soulful and show the personalities of the subjects.