Julie Mehretu: Mapping the Modern World

Artist Julie Mehretu poses for a portrait in her studio on Thursday, August 11, 2016 in NYC / Photo by Landon Nordeman

“I am looking for that space where you can’t have that singular, particular experience. It’s about what is undefined, unstable – and for me, that’s important politically.”

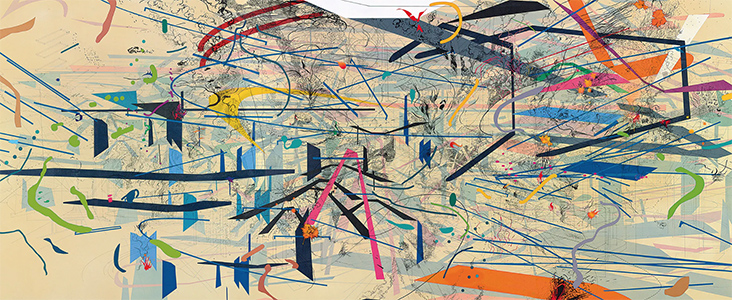

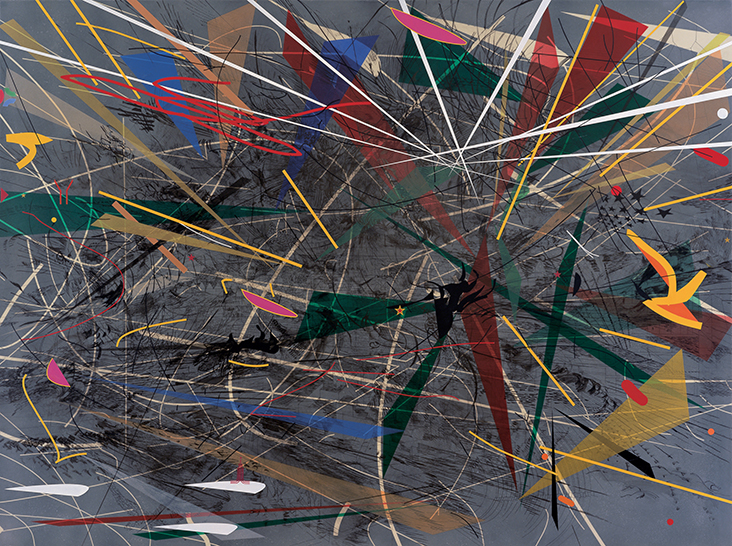

Spidery lines whisper skeletal, architectural structures, coloured streaks swoop and swirl and ink blots become darkened clouds of soot and smoke: this is the electrifyingly complex landscape of Julie Mehretu. She brings together diverse references including urban drawings, fragments of current affairs, comic book motifs, Chinese and Japanese calligraphy, uniting them with an overarching fascination in the contemporary metropolis in all its messy, complicated glory. But unlike 20th century artists who celebrated the modern city as the dawn of a new future, Mehretu’s 21st century vision is fragile and destabilised, exposing the chaotic, disordered nature of our contemporary society as it teeters on the brink of collapse.

Artist Julie Mehretu poses for a portrait in her studio on Thursday, August 11, 2016 in NYC / Photo by Landon Nordeman

Mehretu was born in Addis Ababa in 1970 to an Ethiopian father and American mother. Her family left as political turmoil took over 1977, because, as she says, in reference to the country’s catastrophic widespread war and famine, “things got really bad there.” Heading for America, Mehretu’s family moved between Michigan and Texas; such a wide ranging childhood undoubtedly opened up her world view, allowing her to develop an inquiring mind from an early age. British artist Tacita Dean sees a connection between these early experiences and Mehretu’s later work, commenting, “It goes very deep in her and is part of her makeup as a person. What artists work with is what was put in there in their first 10 or 11 years of life. You can’t separate Julie from what happened to her.”

Setting out to become an artist, Mehretu initially chose to study fine art at the Universite Cheikh Anta Diop, Dakar, Senegal, before receiving her BA in Art from Kalmazoo College in Michigan. At the start of an MFA with the Rhode Island School of Design in New York in the mid-1990s she was working somewhat half-heartedly in an Abstract Expressionist style, as she explains, “When I started my MFA, I was making big, abstract oil paintings that looked gestural and expressionistic, even though I wasn’t interested in them looking like that.”

Through her teacher Michael Young, she discovered drawing could become a vital element to her practice, which allowed her to be “led by instinct and intuition,” saying, “it opened up a way for me to create work.” After graduating in 1997, Mehretu continued to explore the boundaries between drawing and painting; early works were made by layering drawings of architectural and urban map fragments on tracing paper on top of one another, which would then be drawn onto canvas. Describing them as “aerial maps of cities”, and “story maps of no location”, these artworks led to a conceptual way of thinking for Mehretu as she began to liken her process of drawing, layering and moving around to the shifting meta-structures that order our civilisations, considering their implications on the societies that live in them. Though the sources for these artworks came from a wide range of locations, Mehretu admitted in an interview in 2003 that tracing her own lineage was also an important point of departure from which she could open out into wider cultural references, saying, “My fascination was with the numerous conflicting stories, histories and disparate cultures that, through time and place, came together to make me…”

Style and content merged into one as she produced art in a controlled and clean way, with ink and technical pens, the tools used for map making and architectural drawing. These pristine marks were made on a smooth, transparent acrylic resin on canvas, adding to the sleek, polished and digitized look of her work, which could then be recoated and drawn over again as layers were built up over time, as seen in the early work, Back to Gondwanaland, 2000, a drawn on canvas that hovers somewhere between an architectonic system and an abstract, Suprematist work of art.

By 1999 Mehretu was achieving widespread recognition for her large format drawings, paintings and prints, which brought the language of Jackson Pollock and Barnett Newman alive for a new era, combining an awareness of space, layering and abstraction with a polished, synthetic veneer. Her multi-layered references also gave her work a postmodern, ahistorical sense of agency, as she explained in a later interview, “I was collapsing all sorts of historical, social and political periods into one space by layering many drawings of different buildings and cities into one cosmology, into one painting. It was as if I was creating a tectonic view of time and space that was also historical.”

Like many postmodern artists, breaking apart the linear view of history was, in part, a chance for Mehretu to reconsider aspects of past culture that had been ignored or overlooked; this process had great personal significance for her as an African-American woman, who was painfully aware of others sharing her heritage who had effectively been wiped out of history in favour of a predominantly white, male-centric bias. For example, she points out during Jackson Pollock and Wilhelm de Kooning’s era, which had had a profound impact on her as a student, there was also “Helen Frankenthaler, Elaine de Kooning and all these African American women and men. But none of that was considered part of the story.”

During a residency at the Walker Art Centre in 2003, Mehretu worked with a group of 30 high school girls from East Africa, whose journeys and experiences were integrated into a series of new paintings; since this time references to real places, journeys and experiences have appeared in her art in an attempt to fill out a more colourful portrayal of history. The works she made during this residency would also become the first of many “panoramic landscapes” which brim with explosive, turbulent energy, reminiscent of Futurist painter Umberto Boccioni’s famous turn of the century painting The City Rises, 1910, or Wassily Kandinsky’s abstract, sonorous colour explorations, but filtered through a digitized, contemporary lens. Since then, her ambitious, vastly scaled paintings have continued to imbue this same teeming energy, which could just as easily be a cataclysmic point of violent destruction as a jubilant celebration.

From a distance her works appear as abstract forces of motion, while closer inspection reveals a wide array of intricate and meticulously rendered sources, inviting contemplations on micro and macro worlds, as well as our individual places in wider cultural constructs. Sotheby’s auction house writes of this ability to pan out and see the vast systems which attempt to harness human behaviour in relation to her Black Ground (deep light), 2006, “what Mehretu is concerned with is not the singular but the universal and eternal – the complex and multivalent nature of contemporary urban experience and its inherent and inevitable incendiary energies stemming from sheer necessity of expansion.”

More recently, dramatic, catastrophic events from world news have played out amidst her whirling chaos, lending it a doomsday, apocalyptic quality, from the Tahrir Square demonstrations to California’s wildfires and London’s Grenfell tower disaster, moments in time that reveal just how easily the structured fabric of contemporary life can be pulled apart.

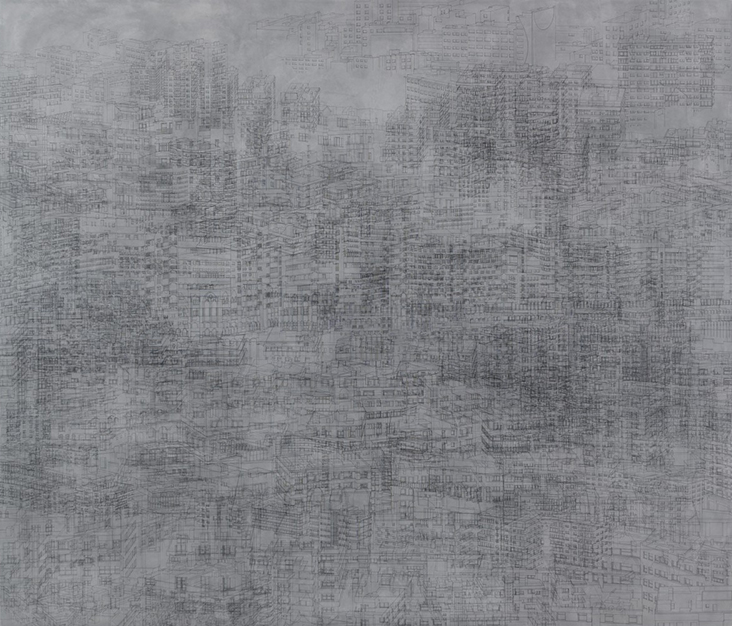

Today Mehretu continues to live and work in New York, but she has also established a second studio in Berlin which she visits frequently; perhaps this is no surprise for a city imbued with the same fragmentary dislocation, loss and reinvention as her works of art. She paid homage to the German capital recently with the subtle, ghostly series Berliner Platze, 2008-9, a melancholic memoriam of all the 19th century buildings destroyed by the Second World War.

Like many larger than life voices, Mehretu has had her detractors over the years, facing accusations of being macho, pompous and even a supporter of US imperialism. But she has remained steadfast and undeterred, earning the MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 2005 and the US Department of State Medal of Arts in 2015, while her paintings now reach into the millions at auction.

The scale and ambition of her work has continued to grow, as has her ever-expanding repertoire of material, which includes stadiums, city squares, amphitheatres, libraries and airports, set amidst fire, smoke, thunderstorms and tornadoes in a decadent, labyrinthine homage to the lucid, fragmentary experience that is modern life. Jonathan Jones, writer for The Guardian describes her magnitude today: “Now and then an artist comes along who turns every critical cliché on its head and proves the experts know nothing about where art is going. Julie Mehretu is one of those heroes.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

Ms. Lesso thank you again for bring to focus a wonderful young artist. Her art and your words bring out her soulful nature.