Kara Walker: A History of Violence

“The silhouette says a lot with very little information, but that’s also what the stereotype does.”

Brutal, shocking and filled with tragedy, Kara Walker’s re-telling of black history aims for the jugular. The artist made her name with cut out silhouettes illustrating bloody, violent acts inflicted upon America’s black population, particularly women, during the American Civil War. Many of the stories she unearths and spreads across gallery walls in all their theatrical horror are ones history has tried to forget, including public lynching, sexual assaults and shootings, while innocent, helpless children look on, signalling the wounds inflicted on generations that followed. Undoubtedly such controversial material has had its detractors, but Walker is deliberately stirring up uncomfortable feelings about deeply embedded cultural trauma and pervasive racism that should not be brushed under the carpet, as she explains, “It makes people queasy. And I like that queasy feeling.”

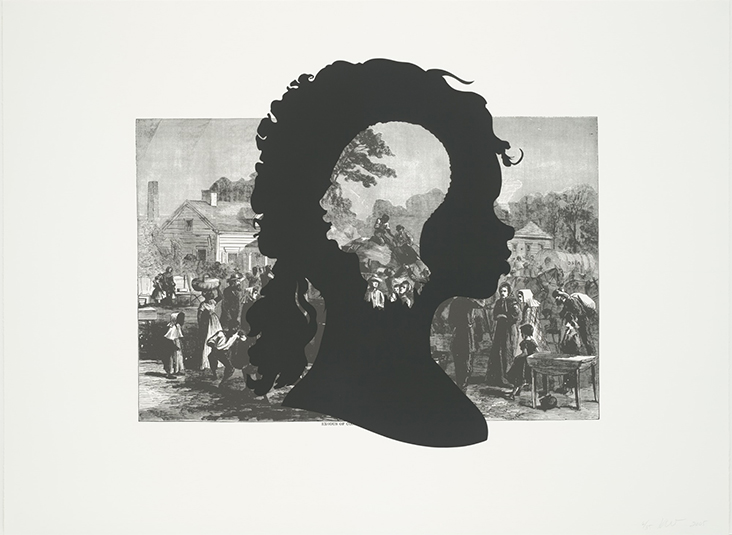

Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta from Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) / Kara Walker / 2005

Born in Stockton, California in 1969, Walker’s father Larry was an acclaimed artist whose work explored socio-political themes; he and his friend, the artist Betye Saar, were among a group who created an empowered message of hope and optimism for America’s black communities. The influence he had upon his young daughter was profound, as she remembered back, “One of my earliest memories involves sitting on my dad’s lap in his studio in the garage of our house and watching him draw. I remember thinking ‘I want to do that too,’ and I pretty much decided then and there at age 2 ½ or 3 that I was an artist just like dad.” Years later Walker’s father would be one of her greatest defenders when she faced harsh criticism – he argued his generation of black artists had fought for freedom of speech and self-expression.

When she was 13 Walker’s father took on a teaching post at Georgia State University and the family moved to the small town of Stone Mountain in Atlanta. In contrast with California’s multi-cultural environment, the Walkers were one of only a few black families living in Stone Mountain and racism was still rife here during this time; they later discovered the town still organised Klu Klux Klan rallies, while Walker faced racist bullying at school, forcing her into the position of outsider. Retreating to the library as an escape, Walker read about Southern American history, education herself on the new, oppressive environment she was immersed in.

In the years that followed Walker went on to study fine art at Atlanta College of Art, before moving on to an MFA at the Rhode Island School of Design. As a student, Walker made large scale, mythological subjects, but she remembers feeling the pressure to convey not only the “black experience”, but to put a positive spin on it, as her father’s generation had, as she explains, “When I started painting black figures, the white professors were relieved, and the black students were like, ‘She’s on our side.’” In retrospect, this confining expectation narrowed her field of study, as she added, “These are the kind of issues that a white male artist just doesn’t have to deal with.”

A turning point came when Walker encountered Adrian Piper’s conceptual art, which showed her a more critical, analytical approach to issues of race in art practice. She wrote, “(Piper) was the first voice that resonated with me, in talking about race with objectivity and sternness.” Rather than promoting an image of unrelenting optimism and hope by glazing over the past, through Piper’s influence Walker began to uncover themes of racial oppression, with an emphasis on the woman’s experience. In one of her earliest silhouette works, Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart, 1994, Walker creates a retelling of Margaret Mitchell’s famous Gone with the Wind story, unravelling the original, romanticised and essentially racist text into a tangle of deceit and lies. Fantasy merges with fiction in works such as this one, while black characters become grossly exaggerated caricatures, almost comic, if it weren’t for the painful truth they unmask.

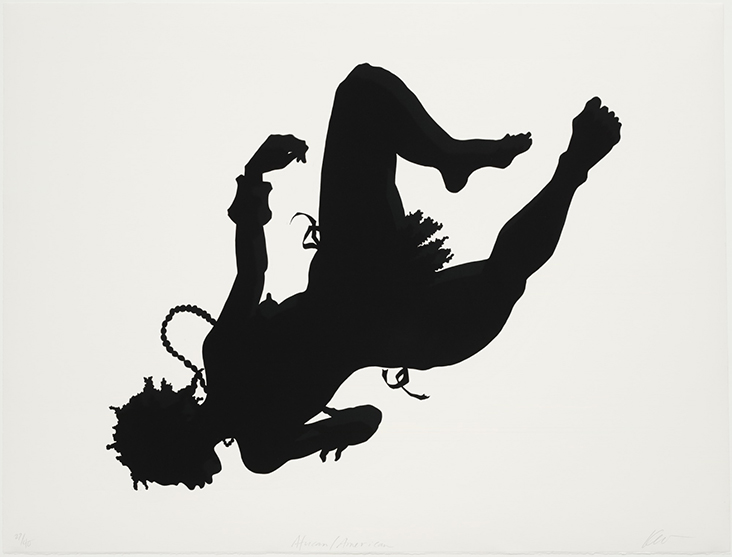

Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey into Picturesque Southern Slavery or “Life at ‘Ol’ Virginny’s Hole’ (sketches from Plantation Life)” See the Peculiar Institution as never before! All cut from black paper by the able hand of Kara Elizabeth Walker, an Emancipated Negress and leader in her Cause / 1997 / Cut paper on wall. Artwork ©Kara Walker, courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co. / New York.

The work marked the beginning of Walker’s signature style, a reworking of the genteel tradition of Victorian paper cuts, which when spread out across the white gallery walls mimic the theatrical, enveloping drama of history painting, a genre that has long been a source of fascination for Walker. Several works made in 1995, including The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven, were made to unfurl in curved spaces, encircling the viewer like a cyclorama while echoing the perpetual cycle of racism as it continues to invade and infect today’s culture. The work makes reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s abolitionist novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852, while also illustrating a panoramic display of horrific acts of torture, murder and assault that was inflicted on slaves in the American South, particularly from white masters and their female slaves. Interwoven into her complex, multi-layered narratives like this one are also elements of whimsical fantasy and intricate detail, merging factual documentation with fiction, mythology and surrealism as she writes, “I’m fascinated with the stories that we tell. Real histories become fantasies and fairy tales, morality tales and fables.”

In another major work made several years later, the extensively titled, Slavery! Slavery! Presenting a GRAND and LIFELIKE Panoramic Journey into Picturesque Southern Slavery or “Life at’Ol’ Virginny’s Hole’ (sketches from Plantation Life)” See the Peculiar Institution as never before! All cut from black paper by the able hand of Kara Elizabeth Walker, an Emancipated Negress and leader in her Cause, 1997, black slaves turn on their white masters, while various acts of sexual aggression take place. Here the black paper of the silhouettes levels the field between black and white figures, lending them a certain ambiguity and blurring boundaries between oppressor and oppressed.

Reactions were mixed to the scandalous and sensationalist nature of her material as Walker soon found herself under attack from artists and the press, who took her parodic representations of African Americans at face value rather than reading them as a critique of the society that produced them. Artist Howardena Pindell expressed the views of many when she wrote, “Walker consciously or unconsciously seems to be catering to the bestial fantasies about blacks created by white supremacy and racism.” Meanwhile, in her defence, Harvard professor and historian Henry Louis Gates Jr. pointed out the greater level of complexity that was being missed in these literal interpretations, arguing in the International Review of African American Art, “Only the visually illiterate could mistake (Walker’s) post-modern critiques for realistic portrayals. That is the difference between the racist original and the post-modern, signifying anti-racist parody that characterises this genre of artistic expression.” Artist Barbara Kruger also celebrated Walker’s bravado, which exposed the absurd and grotesque nature of these stereotypes already in existence by “turning them upside down, spread-eagle and inside out.”

Winning the MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship in 1997 was a mixed blessing for Walker, raising greater public awareness to her art, while simultaneously opening her up to a wider amount of criticism. Betye Saar, a former family friend of the Walkers, organised an aggressive campaign, sending out over 200 letters to various prominent black figures in the realms of politics and art, asking the loaded question, “Are African-Americans being betrayed under the guise of art?” Walker had recently given birth to her daughter and was already struggling with postpartum depression, making the attack all the more vehement and penetrating, as she pointed out, “Essentially, I understood that my attackers had turned me into a fiction; they were vilifying me for making caricatures of blackness by doing the same thing to me.” She points to art from the black liberation movement as “propagandistic in tone and often redundant,” arguing instead that art should allow “black artists to …proclaim our past and struggles.” Although he was shocked by the graphic nature of her material, Walker’s father also publicly came to her defence, supporting his daughter’s right to express herself.

More recently, Walker has expanded beyond the realms of cut paper silhouettes, exploring film, such as Testimony: Narrative of a Negress Burdened by Good Intentions, 2004, in which flat silhouettes become moving puppets lit from behind. Walker creates a strong central female character here, as if reacting with strength against her criticisers, writing, “In Testimony, the Negress has the power.” Another point of departure came in her colossal public art sculpture A Subtlety, or the Marvellous Sugar Baby, 2014, a 35-foot tall sugar coated female sphinx, who has, as writer Roberta Smith describes “undeniably black features and wearing an Aunt Jemima kerchief and earrings.” Situated in the former Domino sugar factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, the work raises awareness to the sugar trade’s dirty, complicated history, a trade only made possible through slave labour.

Walker made it through the initial barriers of criticism to a place of international recognition, featuring in Time Magazine’s list of 100 most influential Americans and holding a retrospective at the Whitney Museum in 2008 while only in her 30s. More recently, on the 2nd October 2019 she will unveil a new, as yet unseen artwork for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, making her the first black woman to fill the iconic space. Her fearless and unflinching ability to delve into the darkest and most depraved corners of American social history and bring them out into the glare of the 21st century have encouraged many more to follow her lead, including Ellen Gallagher, Glen Ligon and Lorna Simpson, as she asserts, “I make art for anyone who’s forgotten what it feels like to put up a fight.”

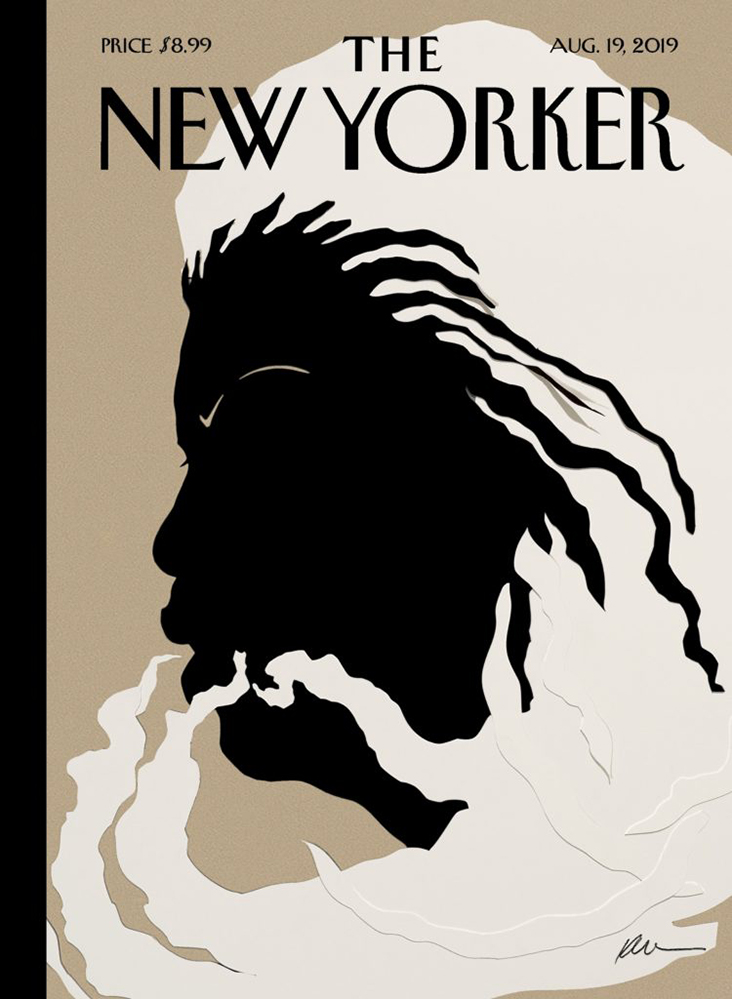

Quiet as It’s Kept / Kara Walker / 2019 / a New Yorker cover paying tribute to the late author Toni Morrison. Courtesy of the New Yorker.

Feature image: ‘Black Out: Silhouettes Then and Now’ / Kara Walker

One Comment

Leann Runge

BEST article yet! Thank you for bringing it to light. I want to learn more about Ms. Walker and her art. It’s so important.