Ellen Gallagher: Quiet Subversion

“Repetition and revision is central to my working process, this idea of stacking and layering and building up densities and recoveries.”

Ellen Gallagher is a minimalist at heart, arranging tight grids and decorative repeat patterns that echo the measured abstractions of Sol LeWitt or Agnes Martin. But lean in closer; woven tightly into the fabric of her dense networks are troubling, unsettling motifs that reference racial stereotypes or oppressions from throughout history, particularly those placed upon African-American women such as her. There is also a rich materiality to her work, as ink and paint stained fragments are cut apart, reconfigured and overlaid with new materials, an apt metaphor for the organic growth of cultural identity over the centuries. Reflecting on the multi-layered references in her work, she writes, “I do think you can change the past and the present somehow. Even if something has already happened, it doesn’t mean it’s settled.”

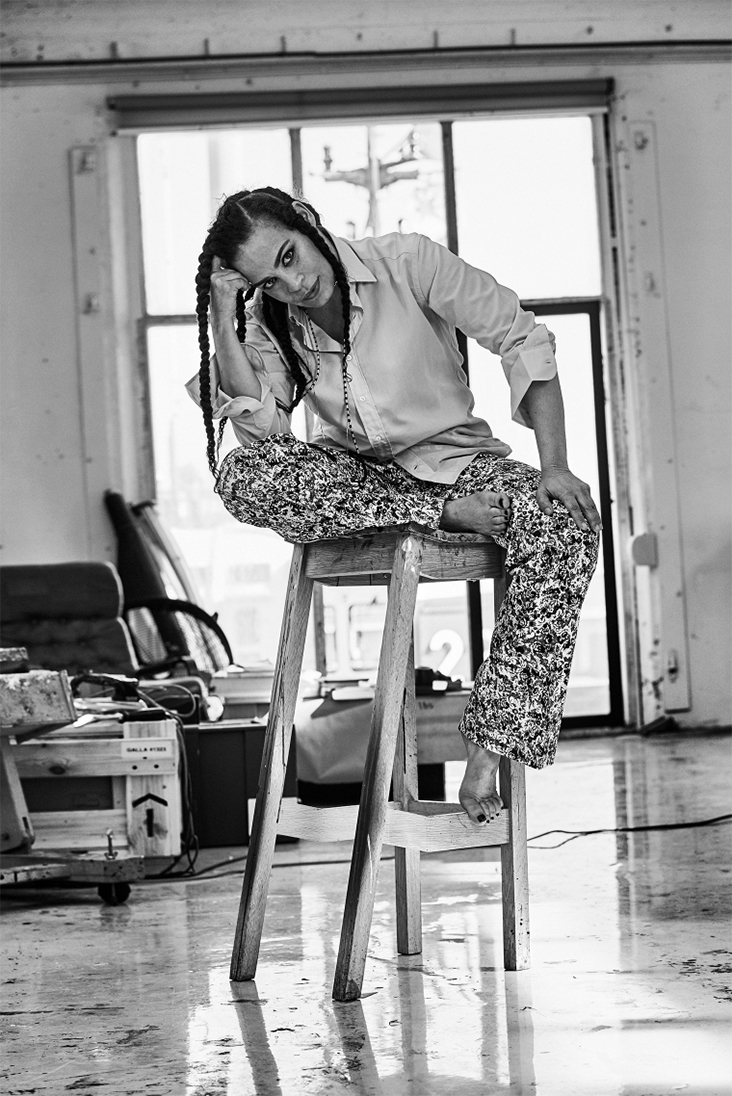

Born to bi-racial parents, Gallagher’s father was African-American and her mother Irish-American. Growing up in Providence, Rhode Island, Gallagher was raised by her single mother in a racially mixed neighbourhood, something the artist saw as a deliberate move to avoid any feelings of exclusion. She attended the strict Quaker School Moses Brown, leaving at 16 to join Oberlin College in Ohio. In a bid to find some freedom Gallagher spent one term living on a fishing boat in Alaska, studying water snails, although she admits she was feeling directionless and lost at the time, describing her feelings in a recent interview: “What am I doing on this boat studying pteropods in the middle of the night, looking at these things under a microscope? How is this going to mean something to who I am? It’s that feeling of being 20 and not knowing what’s coming next.” As an adult, this ability to live in a state of doubt and unknowing would become the backbone of her artistic practice.

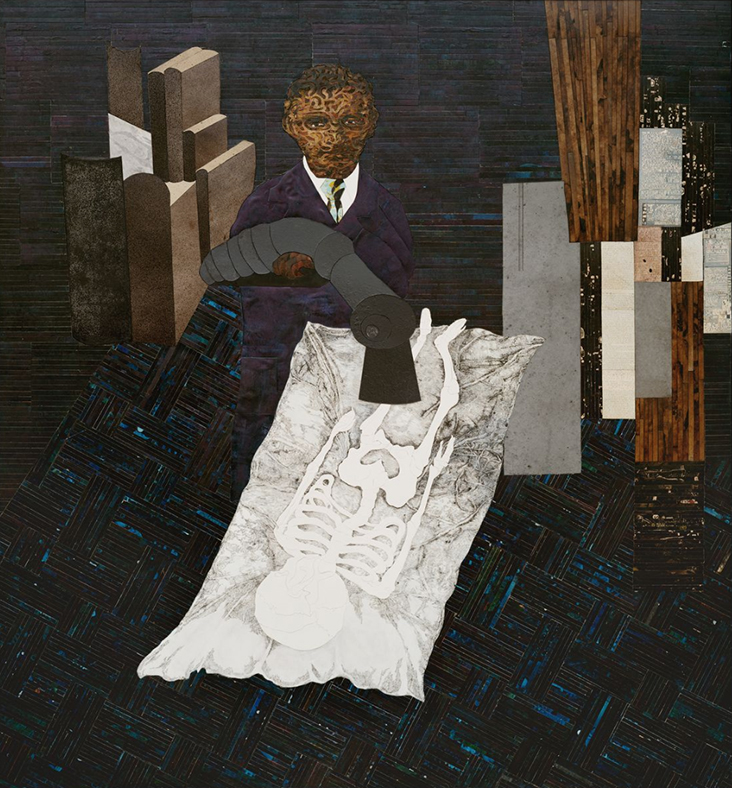

Bone- Brite / Ellen Gallagher / 2009 / Ink, graphite, carcoal, oil, palladium leaf, and cut paper on canvas

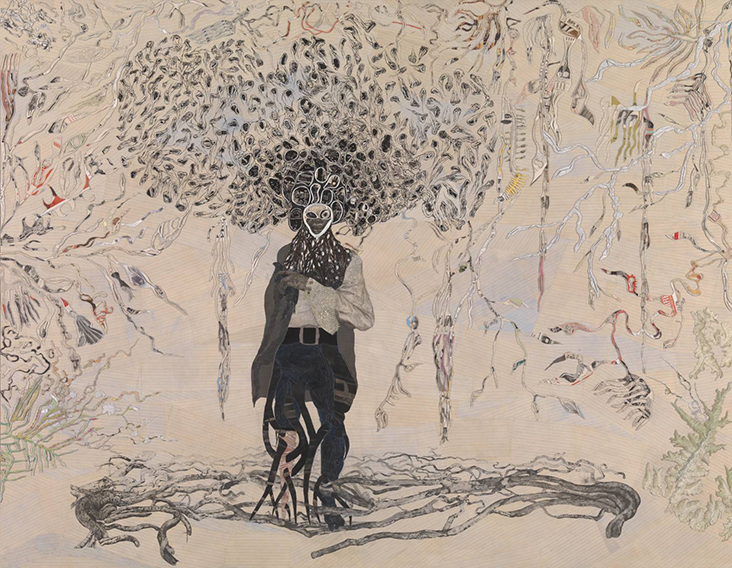

O.K. Corral / Ellen Gallagher / 2008 / Ink, polymer medium, varnish, indentations and cut printed paper on canvas

Returning to dry land and pursuing various odd jobs, Gallagher eventually found her way to art school at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and later at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in Maine, where she met and befriended various artists including Kiki Smith. A rich variety of subjects were already making their way into her complex and tactile practice, such as oceanography, microscopic organisms, images from popular culture and American abstraction, but tying all these references together was an underlying awareness of Black culture and language.

Not long after completing a residency in Provincetown Gallagher’s art caught the attention of several major institutions; she was selected for the Whitney Biennal in 1995 and held a major solo show at Mary Boone Gallery in New York, where she exhibited the first of what would become a major series; sheets of lined paper covered canvases in a sea of horizontal lines, a nod towards Agnes Martin’s Minimalist paintings and Gertrude Stein’s repetitive writing, but across each line were hand drawn rows and rows of minstrel icons, such as what she calls “Sambo lips” or “bug eyes”, a reflection of the insidious and destructive infiltration of racial prejudices. Arranging such controversial subject matter into grids is, as she points out, a reflection of society’s “ordering principles”, which can become as rigid and confined as her tightly packed lines.

In the years that followed Gallagher met her lifelong romantic and artistic collaborator Edgar Cleijne and the two soon began living and working between Rotterdam and New York, absorbing the cultural references from each city. Meanwhile Gallagher’s career was growing as a greater range of complex ideas made their way into her practice. In 1998 she made a series of huge, black monochrome canvases, including Untitled, 1998, which further explores Black stereotypes with her trademark lip motifs forming intricate areas of detail and pattern. The shiny veneer of these paintings is intentionally evasive and slippery, as she plays with the cultural denial or glossing over of racist stereotypes that still prevail today. She writes, “I really see the black paintings as a kind of refusal. Even when reading them – if you stand in front of them they go blank and then if you stand at the side you only see a little.” Writer and curator Claire Doherty adds, “Unlike other works, this painting’s unyielding surface deflects detailed investigation. The mechanism of reduction in the creation of the stereotype is parodied in the negation of individuality.”

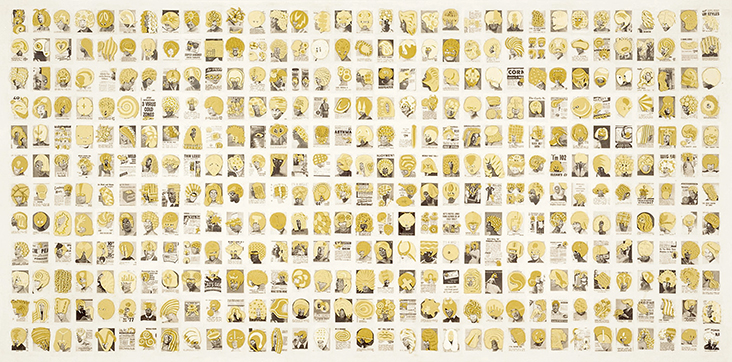

In the 1990s Gallagher also brought archival material into her art, including imagery lifted from African-American magazines including Sepia, Ebony, Tan and Black confessions, which she admits drew her in like a moth, writing, “I could go through a decade in an hour. I could disappear into these things.” It was the advertisements that caught her eye in particular, which promoted wigs, hair-straighteners and skin lighteners aimed at African-American women, which she pored over with a curious fascination. These images made their way into her practice, which she drew on and cut into, removing the eyes in an act of depersonalisation, later adding blonde wigs made from plasticine, along with elements of velvet, googly eyes and oil, a parodic play on the negating self-image these adverts promoted. Gallagher has since brought these collages together into various collective artworks, including the famous DeLuxe, 2004, which has been exhibited all around the world.

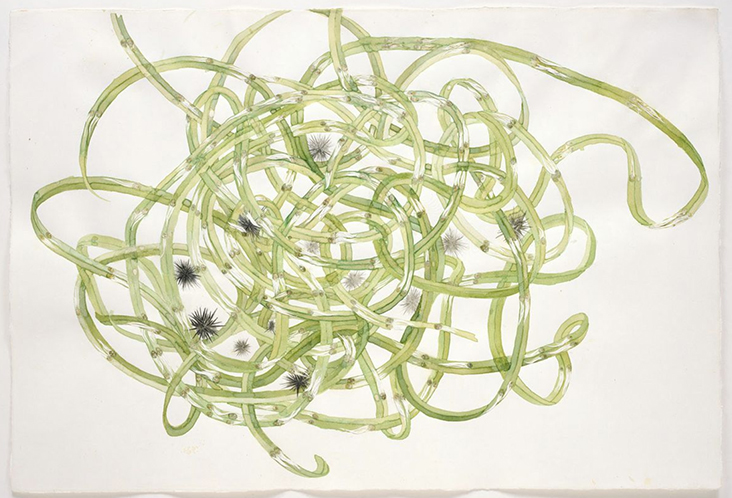

The ongoing series, Watery Ecstatic, begun in 2001, is more organic and fluid. On one hand, it is a nod towards Gallagher’s early experiences on a fishing boat, but she also references the mythical aquatic kingdom of Drexciya, created by the contemporary electronic band of the same name, who envisioned an underwater world led by the children of pregnant women who were thrown overboard during the transatlantic slave trade, often for simply being “sullen.” The curious, imaginary forms she creates belong to a fantastical world beneath the sea, while shapes cut from thick paper are made to resemble scrimshaw, the process of carving whale bones. As with much of her practice, delicate, watery imagery hides within its depths the dark truths of African-American history, melding together beauty and deep tragedy as hidden motifs including the faces of Black women nestle within their tendrils.

Two major retrospectives in 2013, one at Tate Modern and the other at New York’s New Museum revealed the gradual evolution of her practice since the mid-1990s while simultaneously cementing her place as a 21st century giant of contemporary art, as Tate curator Juliet Bingham calls her “one of the foremost artists to have emerged from America in the 1990s.” Widely recognised as an integral voice in the development of Post-Minimalist language, Gallagher combines all the delicious pleasures of making that marked 20th century abstraction with painfully significant content that is so pertinent today, a language that is mirrored in the work of her contemporaries including Julie Mehretu, Lorna Simpson, Kara Walker and Chris Ofili. But Gallagher’s ability to sew together a rich language of pain and uncertainty from African-American culture, particularly relating to women’s experience, is unique and unrivalled. Her work evolves slowly, uncurling without narrative into dreamy, mystical forms with a life force of their own, formed from the messy complicated soup of history as she argues, “…it’s okay to work from doubt. You need to be willing to not know.”

One Comment

Vicki Lang

What a beautiful soul. Her art has transformed along with her spiritual growth. Can’t wait to see what she does next. And as always your words have brought her to life. thank you.