Rachel Whiteread: Material Space

“My work has affected people over the years … because it draws people’s attention to … the things in their lives. There’s a certain amount of humility that goes with that.”

Rachel Whiteread’s ghostly sculptures transform empty, forgotten space into solid mass. Drawing us to unusual, forgotten places is her forte, from the dark recesses of a childhood cupboard, the dusty space under the stairs or the interior of an abandoned house. That these uncanny inversions are made from sites once populated by people, whose traces are still visible in her work, is vital to her practice, lending it the weight of human history. Whiteread’s casts first caught the world’s attention in 1990s London when she became the first woman to win the Turner Prize; all around her the Young British Artists’ sensationalist art caused a furore and Whiteread was there to witness it. But her voice was more steadfast and considered as she built herself a rock solid foundation based on determination and hard work, rather than ego or bravado. Looking back, she remembers, “I think the difference between me and some of the other YBAs was that I was ambitious for the work, and not ambitious for myself.”

Whiteread spent the early part of her childhood in Ilford, Essex, before moving with her family to London when she was 7 years old. Her mother was an artist, who took part in various feminist exhibitions at London’s Institute of Contemporary Art in 1980s, while her father, a geography teacher, converted part of the family home into a studio for her. Whiteread and her two older twin sisters were fascinated by their mother’s studio, and making seemed the most natural activity to Whiteread as she remembers back, “When I was a kid … I was totally interested in the physical world and would always be making something, playing around with bits and pieces I’d found, changing them from one thing into another.”

The local progressive public school was a mixed bag for the young artist, opening her eyes to the wider world in a way that would remain with her for life as she recalled, “I kind of loved it; it was a big world soup, fights all the time, influxes of Bangladeshis, Greeks, Turks, Romanians, a really interesting bunch of people all thrown together.” But amid the social maelstrom she struggled to focus on academia, remembering, “I wasn’t good at school. I didn’t behave or sit down, I mucked about, doing what I could to get by.” As a young teenager she rebelled against her mother by rejecting art for a brief spell, but by the time she was in sixth form she was determined to pursue art school.

In the early to mid-1980s Whiteread studied painting at Brighton Polytechnic, although towards the end of her degree she was already moving away from two-dimensions. “I couldn’t make things stay on the wall,” she recalled, “they always ended up on the floor.” Her tutor, British artist Richard Wilson, taught her how to make casts from ordinary objects including a humble spoon, which opened her eyes to the technique’s transformative potential.

A postgraduate degree in sculpture at The Slade School of Fine Art followed, where Whiteread was taught by Alison Wilding and Phyllida Barlow; by the end of the course she had found her signature style in its infancy, producing plaster casts of small empty spaces. Closet, 1987, was made from a cupboard interior which she covered in black felt, a reference to a place she used to hide in as a child. Shallow Breath, 1987 also tapped into the fear and wonder of childhood, as a plaster cast of the space under a bed was leant against a wall, taking on a strangely human form, all the more poignant when made not long after the death of the artist’s father.

After graduating Whiteread set up a home in East London and moved into a shared studio complex at Carpenters Road in Stratford, where her austere workspace had “no windows and lots of mice.” It was a shabby, run down and dangerous area, but Whiteread soon befriended artists in the neighbouring spaces, with a shared sense that they were in the same struggle together. She remembered back to a place where many of today’s leading artists were still finding their feet: “There were a few of us: Grayson Perry, Fiona Banner, Fiona Rae, Simon English. It was a sort of silent club: if you could survive Carpenters Road, you could survive anywhere. It was the Badlands.”

In her first solo show at the Carlisle Gallery in Islington in 1988 Whiteread exhibited Closet and Shallow Breath, along with a further two casts: Mantle, a cast from inside a dressing table and Torso, taken from a hot water bottle interior. Titles made allusions to the human body and the spaces we inhabit, quiet, contemplations on the human imprint that is left behind on ordinary objects, but there is also a sense that she is turning the domestic inside out, subverting the traditional feminine spheres into something altogether more powerful, sinister and threatening.

The process of working with plaster also allowed Whiteread to develop a rich material patina by picking up traces of the object, as she explains, “if you’re casting the underside of a table, it’ll take colour from the table and make a kind of fresco on its surface.” That this gallery was a small domestic space made it the ideal setting for her intimate subjects. Whiteread showed just four works but they all sold, giving her the financial incentive and emotional impetus to carry on.

In 1990 Whiteread made her breakthrough work, Ghost, 1990, a cast of an entire Victorian living room in North London. Monumental in scale, the work became a haunting memorial to a forgotten place, while the process of casting gathered evidence of human life including soot in the fireplace, intricate wallpaper patterns and scratched, worn skirting boards. Whiteread spoke at the time of her process, saying she was “mummifying the air inside the room,” nodding towards the uneasy, embalmed quality of the work.

Throughout the 1990s Whiteread’s career continued to rise as her work became ever more ambitious. She was included in the group shows Sensation and Brilliant with the leading YBAs including Damien Hirst, Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin, even though she was somewhat removed from their wild, attention grabbing antics. Even so, a media frenzy was on its way. In 1993 Whiteread embarked on her most ambitious project yet, titled House, in which she filled an entire three story house set to be demolished with concrete and removed all trace of brickwork. Despite its vast scale, the work had a distinctly anti-monumental quality; as a negative house seen in reverse it was a powerful commentary on the tragic demise of London’s tenement communities and a haunting remnant of what once was. As with much of her sculpture, she undercut the age-old, male driven canon for monolithic monuments, turning this tradition on its head. Opinions on the work were divisive, with many of the area’s residents signing petitions to have it removed.

The project was even awarded the “worst artist of the year” award by the K Foundation, a transgressive organisation set up by former musicians KLF, who blackmailed Whiteread into taking a £40,000 prize from them by threatening to burn the money if she refused to accept it. Whiteread eventually took the cash but gave a substantial amount away to the homeless charity Shelter and various arts grants, while the whole process had left her reeling, as she explained, “I’d made House and I was something of a physical and nervous wreck… the whole thing was too much stress really, and looking back it is a bit of a blur.” House was eventually destroyed by the local council in 1994, much to the dismay of the British art establishment, but it was instrumental in leading to Whiteread’s Turner Prize win in 1993.

One year later Whiteread’s notoriety had furthered her career as she was selected to represent Great Britain at the Venice Biennale. In the same year she was invited to create a huge Holocaust memorial for Vienna’s Judenplatz, although the project took five years to be completed. The culmination was a vast concrete cast of an old library with the book titles facing inwards, known as The Nameless Library, a brutal reminder of all the untold, unwritten stories that will never be. Given the sensitivities of the subject matter, Whiteread battled against criticism throughout the development of the project, later observing, “The politics were horrendous, but I’m happy at the way people seem to respect the piece and use it as a place to think about what happened.”

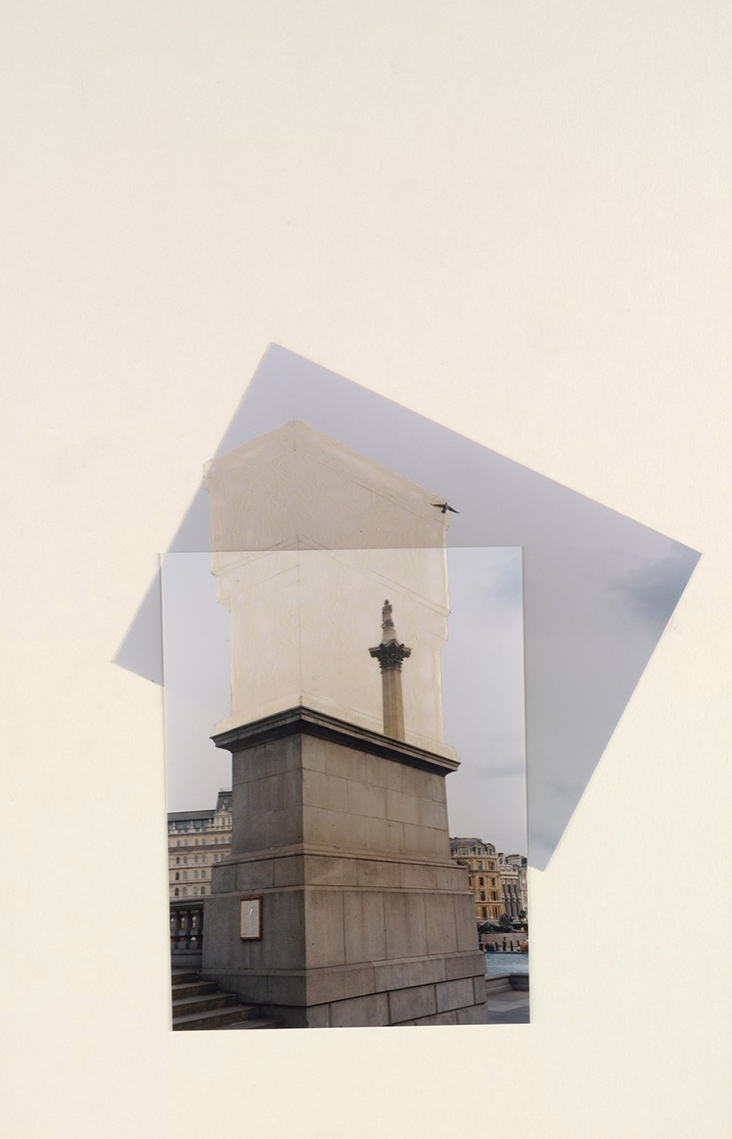

Trafalgar Square Project / Rachel Whiteread / 1998 / Photographic collage and acrylic on museum board

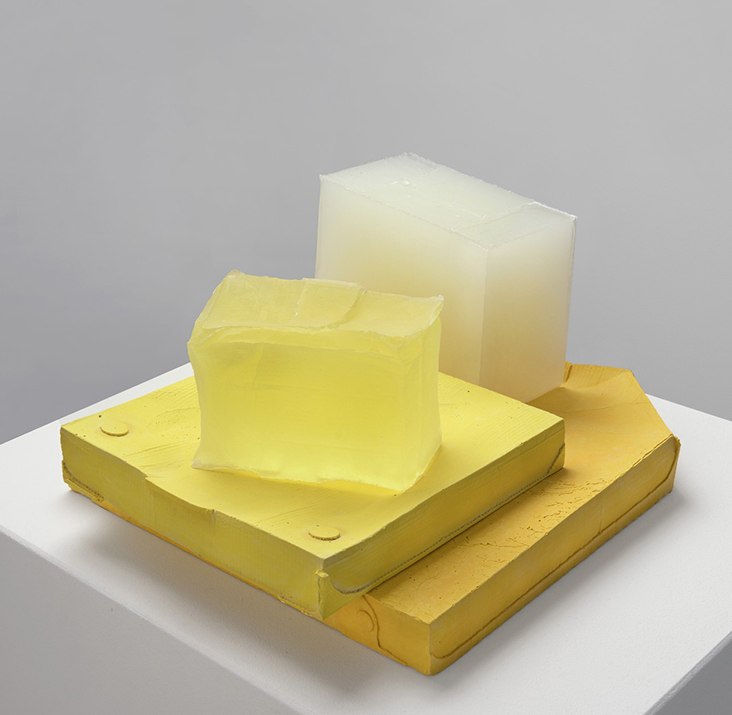

Over the next few years Whiteread began exploring the spectral ephemerality of transparent resin, seen in her Water Tower, 1998 on a rooftop in New York’s Soho district and Monument, 2001, on London’s Trafalgar Square, which reflect, absorb and merge with their context. The nature of her sculptures also gradually shifted from singular motifs towards collective groupings displayed on mass, as seen in Untitled (One Hundred Spaces), 1995, made from the empty spaces below 100 different chairs, cast in seductively coloured translucent resin to resemble squares of jelly.

In 2003 Whiteread had her first son with her long-term partner, the sculptor Marcus Taylor. While she was pregnant her mother passed away, but it took the artist over a year to summon the strength to go through her possessions. The gradual process of sorting through old memories with her two sisters led Whiteread to create Embankment, 2005 for Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall. Inspired by an old cardboard box which her mother had repurposed many times over throughout her childhood, Whiteread produced 14,000 casts of used cardboard boxes in white plaster, allowing the plaster to soak up all the imperfections that traced each item’s history. Each cast was then reproduced in translucent polyethylene, lending them an eerie, ethereal quality. There is an uncanny dichotomy between the austerity of white cubes seen on mass and the traces of human touch, life and experience only seen close up. Boxes teeter and balance on top of one another as if on the brink of collapse, another anti-monument, and perhaps a nod to the chaos underlying much of society’s supposed order.

Whiteread had her second son in 2007, while her work made a shift towards a smaller scale, allowing her to return to the physical engagement with materials that she had sorely missed from her early career, as she explains, “I changed my way of working a few years ago in that I used to have lots of assistants and then realised that wasn’t for me. A lot of the early work is based on my size and what I could lift. I still bring in people to help me when needed, but I love doing the smaller things myself and I try to keep my touch on the work. It goes back to the beginning.”

Tree of life / Rachel Whiteread / 2012 / Bronze, premanent installation at Whichchapel Gallery, London

In recent plaster and resin works she has also introduced more colour, as seen in her deliciously pastel toned Line Up, 2007-8, made from casts of toilet roll interiors. More recently, in a poignant memory to the city of London Whiteread was asked to create a frieze for a blank space above the Whitechapel Gallery for the 2012 London Olympic Games which she chose to decorate with cast golden leaves; titled Tree of Life, she called the work “a gift to the area” where she continues to live and work.

Recent accolades reveal Whiteread’s well-earned status today, including an Order of the British Empire (OBE) in 2006, and a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 2019. Her ghostly, sensitively handled sculptures exist in urban and rural sites around the globe, quietly continuing to weather, age and gather moss as they gradually become absorbed by their surroundings, while their deliberately anti-monument stance is a potent challenge to the patriarchal realm of public art. Reflecting on the raw materiality of her life’s work, artist and writer Matthew Collings concludes, “The effectiveness of her work lies in ingenious and gentle richness, the emotion of shapes and surfaces, and not in a sledgehammer effect of big statements and shattering challenges.”

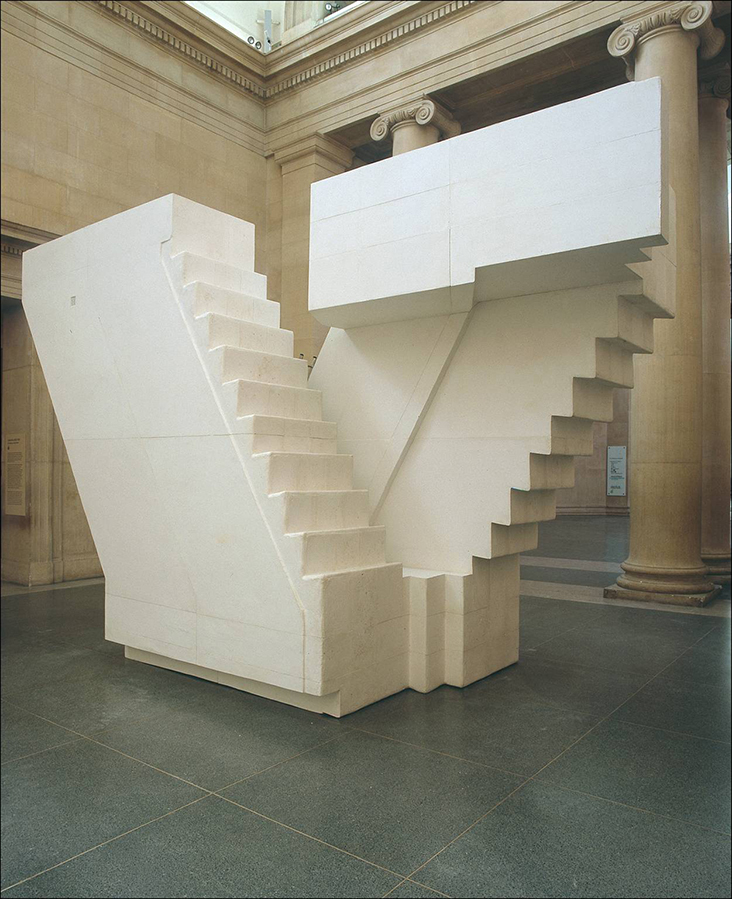

Feature Image: Untitled (Rooms) / Rachel Whiteread / 2001 / Plaster, fibreglass, wood and metal

Leave a comment