Marlene Dumas: Dangerous Beauty

“There is no beauty, if it doesn’t show some of the terribleness of life.”

Dark eyes fall into pits of despair, a shaky, misshapen hand muffles a scream and a deathly pale face seems to catch its last breath of air; such is the hauntingly compelling world of Marlene Dumas. “I’m not good at making pretty things,” she confessed in a recent interview – instead she loads her paintings with the macabre, sublime truth of the human condition. Her career has been on the rise since the mid-1980s and with more than 15 of her paintings selling for over $1m at auction she is ranked as one of today’s most expensive living female artists. Sexism still prevents her paintings from hitting quite the same high notes as her male equivalents, but as a female, expressionist painter, a field which has been largely dominated by men, she has been hugely influential on the next generation of subversive women painters. Contemporary artist Chantal Joffe argues, “I think she’s the greatest living painter, whether she’s a man or a woman.”

Dumas was born in Cape Town in South Africa and grew up in a nearby farm at Kuils River, where her father ran the modest family vineyard and her mother was a homemaker. They were a large, boisterous family who spoke mostly in Afrikaans, with two older brothers, three grandparents and two cousins living on the same stretch of land. She was contended amongst their lively, friendly competitiveness, remembering as a young adult, “I didn’t want to leave them at all.” Dumas’ father died when she was 12 and as her personal life darkened, so too, did the political climate around her, with talk of apartheid dominating family discussions. With some disbelief she remembered back, “People really did think that the white European settler and black indigenous cultures were too different to mix and that only trouble seekers were dissatisfied…”

At her strict boarding school in Stellenbosch, Dumas was a rebellious tomboy who became known for breaking the rules, but she soon discovered a natural aptitude for art, developing an early fascination with the human figure. Growing up, there were few galleries around her, and television was not introduced to South Africa until 1976, so much of her early visual education came from printed reproductions in books and magazines; mediated imagery took on even more agency and danger when all images of the anti-apartheid revolutionary Nelson Mandela were banned.

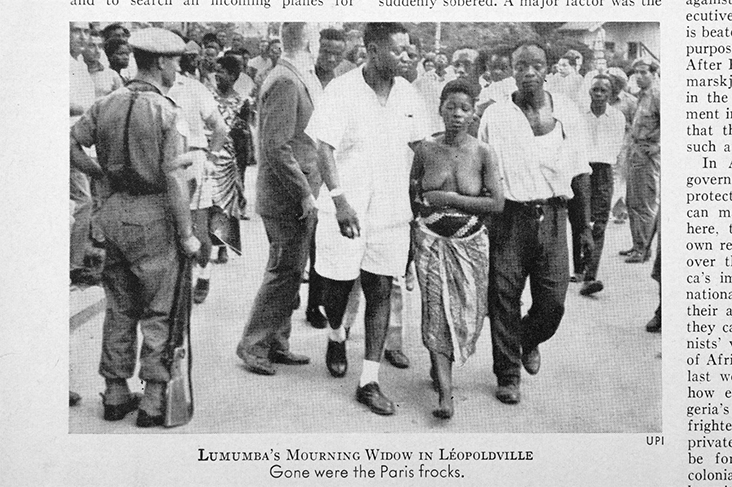

Pauline Lumumba in mourning for her husband, the former Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo. The image served as the inspiration for several works by Marlene Dumas via The New York Times Magazine

On leaving school Dumas enrolled at the English speaking Michaelis School of Art in the University of Cape Town, a period which was a real eye opener, as she described, “I was 19, it was the year 1972, and I’d never sat with a person of colour following the same classes before. Never had dinner with a Jewish or Muslim family before. Was introduced to the poetry of Allen Ginsburg … Was introduced to the films of Ingrid Bergman, Resnais, Godard… and the plays of Jean Genet, Tennessee Williams and Athol Fugard.” Ideas around conceptual art, body art and performance flooded her consciousness, while her photography tutor introduced her to the psychological tensions of photographer Diane Arbus. But it was Jackson Pollock, Pablo Picasso and Roy Lichtenstein that really stuck, making her realise she wanted to be a painter most of all.

In 1976 Dumas won a two year scholarship to study in the Netherlands at the small, progressive art school Ateliers 63 in Amsterdam. With issues around apartheid raging throughout South Africa, Dumas was ready to leave, but in Amsterdam she often felt like an outsider, judged for her status as a white South African. Bit by bit she slowly found her way, adapting to the new culture around her. Studying Psychology at the University in Amsterdam helped her to integrate with the wider community and she befriended various artists including Dick Jewel, and Paul Andriesse, who would later become her art dealer.

Amsterdam’s culture of boundless, uncensored freedom drew her in and she began to read avidly, remembering Amsterdam as the place where “ I read all the books that were banned.” The magpie aspect of her art also blossomed as she became a prolific collector, gathering photographs, postcards and newspaper clippings that would start making their way into her art as multimedia collages, revealed in her first solo show in Paris in 1979. These images were carefully selected for their emotional potency, images that she described as “familiar to almost everyone, everywhere,” adding, “I deal with second-hand images and first hand experiences.” With works including Love Hasn’t Got Anything to Do with It, 1977 and Tenderness and the Third Person, 1981, she combined deeply expressive mark making with ripped apart imagery, lending a performative element to her art.

Over the next few years Dumas took part in several major international shows including Documenta VII in 1982 and the Biennale of Sydney in 1984, where her work was in a small room next to larger displays by Mike Kelley and Anselm Kiefer. The experience ignited in her a passion and ambition like never before as she remembered, “I was unknown at that time. And nearby there were these vast pieces by those guys, and they looked so heroic. It made me realise that I wanted to compete … with the boys.”

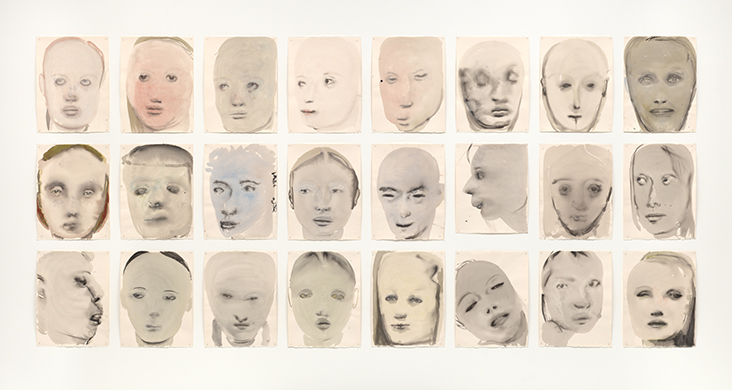

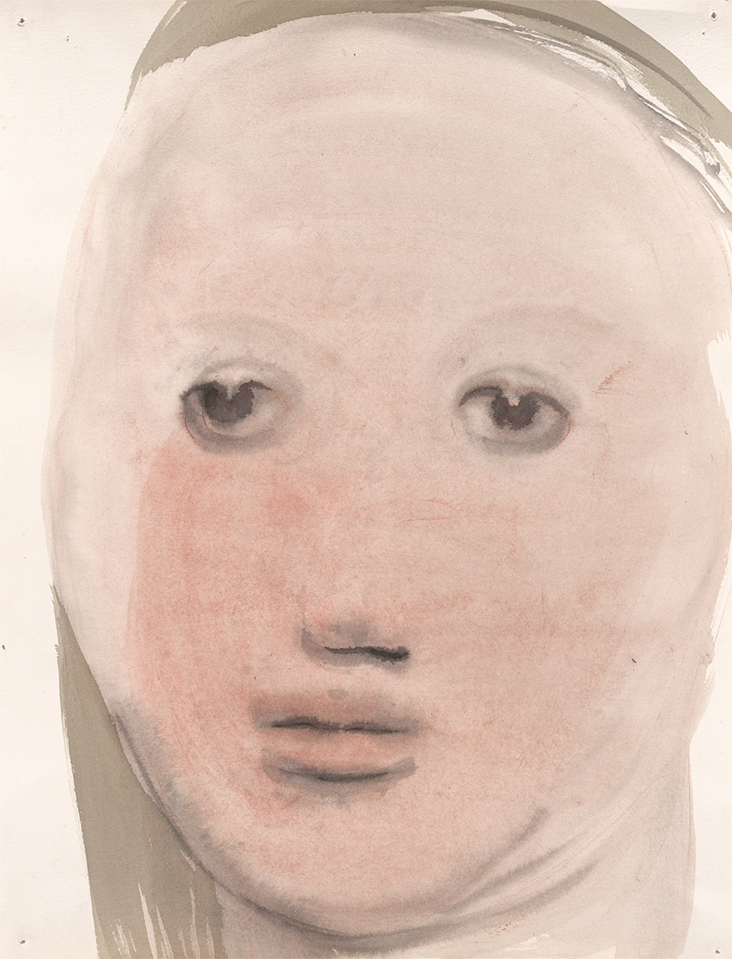

Back in Amsterdam Dumas was on fire, as painting became her primary focus. A solo show in 1985, The Eyes of the Night Creatures, revealed a new series of closely cropped faces with an unnerving psychological tension, loosely based on polaroids, found photographs and film stills. Painting through the mediated lens rather than from life created a distance between her and the subject, adding to their eerie, voyeuristic unease, particularly since some of them were long dead. “They didn’t know that I’d do this to them,” she wryly observed, “They didn’t know by what names I’d call them…”

In the years that followed Dumas fell in love with Jan Andriesse, the cousin of her dealer Paul, and they were soon living together in Amsterdam. As part of a young couple she reflected on a non-sentimental view of motherhood, as children took on adult expressions and a wilful, determined independence, seen in the steely eyed and startlingly mature Die Baba, 1985. In 1987 she became pregnant with her own child, painting herself pregnant, and later making a series of studies of her daughter, reflecting the whirlwind of complex emotions surrounding pregnancy and childbirth. The First People (I-IV), 1990, was loosely based on photographs of her baby daughter and her friend’s son; when seen on such a huge scale these mega-babies incite conflicting emotions, conveying some sense of the overwhelming beauty, fascination and fear of early motherhood.

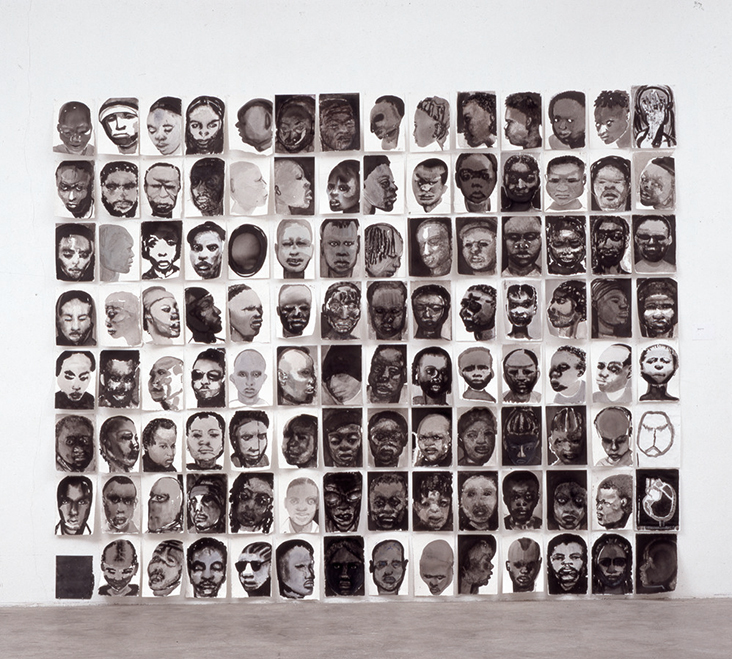

Dumas also began to make politically motivated works during this time, including Black Drawings, 1991-2, a grid of over 100 minimalist ink studies of black heads, a nod towards the racial tensions that marred her childhood. Seen together, they are a powerful defence against the racial inequalities of apartheid, which tragically lost sight of the individual amongst the crowd. Painterly and visceral, they are on one hand an exploration into the abstract qualities of ink on paper, yet also a celebration of the political, cultural and artistic properties associated with black, as she wrote, “it’s … about blackness as a positive state, and the work is a tribute to black as a beautiful colour.”

In the following years Dumas began painting both close portraits and full bodies with an unflinching eye, distorting the original source – faces have asymmetrical features, gaping mouths and cavernous eyes, while bodies grow bulbous bellies and elongated limbs or are bound, gagged and tied. Aqueous, sumptuous layers of paint, often in sickly greens and blues, recall the chilling shadows in Richard Walter Sickert’s London streets where criminals lurk. Some of her figures are ones from the public eye we might recognise, for better or worse: Amy Winehouse, Barack Obama, Oscar Wilde, Phil Spector, Naomi Campbell, while others remain anonymous, removed from their social context.

In one of her most famous works she painted her own daughter, The Painter, 1994, with her hands smothered in thick red paint that resembles blood, while washed out colours, a sombre glare and disappearing legs transform her into a ghostly apparition. This work is significant culturally for Dumas, as a reflection on the changing role of women, including herself, not just in the art world, but in society at large. “Historically painting was seen as female,” writes Dumas, “but, the males were the painters, and the females the models. Now,” she adds, “the female (the daughter) takes the main role. She paints herself. The model becomes the artist. She creates herself. She is not there to please you. She pleases herself.”

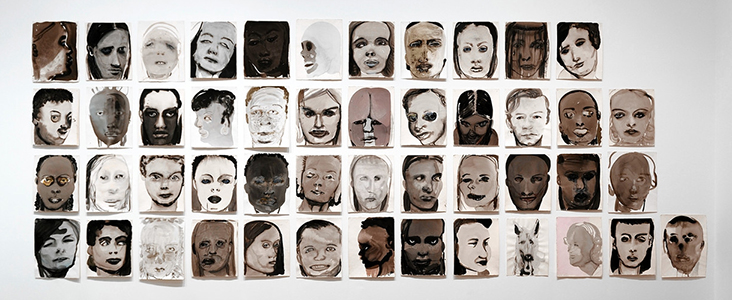

Dumas began compiling the series Rejects in 1994 and continues to edit and add to it today, a collection of works previously rejected from her other series’, revealing the self-effacing, dark humour that underlines much of her practice. There is also a canny slant on the constant failure and rejection many artists face on the slippery slope to success, as she explains, “…you can’t really fail because you’ve acknowledged that you’ve failed, so I like that play … it is serious but it’s also playful; it is about images but it is also about the material and the medium and all the conflicts or tensions between those aspects.”

Difficult human emotions continue to come bubbling to the surface in much of her recent work, including love, sex, death and grief, as her strangely beautiful figures teeter between fragility and threat. When her mother died in 2007 the themes of loss and loneliness became tangibly real to her as reflected in a new series, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Made from still film shots, Dumas painted various famous movie icons as tears of torment roll down their faces, writing, in homage to her beloved mother, “I made the stars and the gods weep for her.” A further layer of complexity is added in Dumas’ choice to paint actresses rather than real people, reminding us that mediated images rarely give the whole story.

Dumas continues to live and work in Amsterdam today and her international reputation has continued to expand, with paintings in museum collections all around the world. In Saatchi Gallery’s landmark The Triumph of Painting in 2004 and at a huge solo retrospective at Tate in 2015, Dumas has been placed as the international matriarch for a new brand of figurative painting that is lively, fresh and progressive, reflecting the complexities of contemporary identity. Her persistent probe into uncomfortable, yet human territory has influenced swathes of artists since, including Cecily Brown, Jenny Saville, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Chantal Joffe, Jenny Saville Elizabeth Peyton, Dana Schutz and Lisa Yuskavage, breaking down the wall of prejudice surrounding a medium that has been dominated by men for centuries. Writer Claire Messud fights the case for Dumas’ outstanding practice, describing her as “One of the most provocative painters of the human form,” adding, “Dumas doesn’t match the stereotype of artist as solitary genius. Her way is chaotic, more responsive and uncertain – and that is her brilliance.”

Feature image: Rejects / Marlene Dumas / 1994–ongoing / Ink, acrylic paint and chalk on paper

2 Comments

Trish Jakielski

Thanks for making we aware of yet another interesting artist. The realism of her works – and yet the “something more” – is truly wonderful. The faces series was particularly interesting. This is a wonderful series.

Vicki Lang

Thank you for another delightfully informative article.