Anne Truitt: Inner Eye

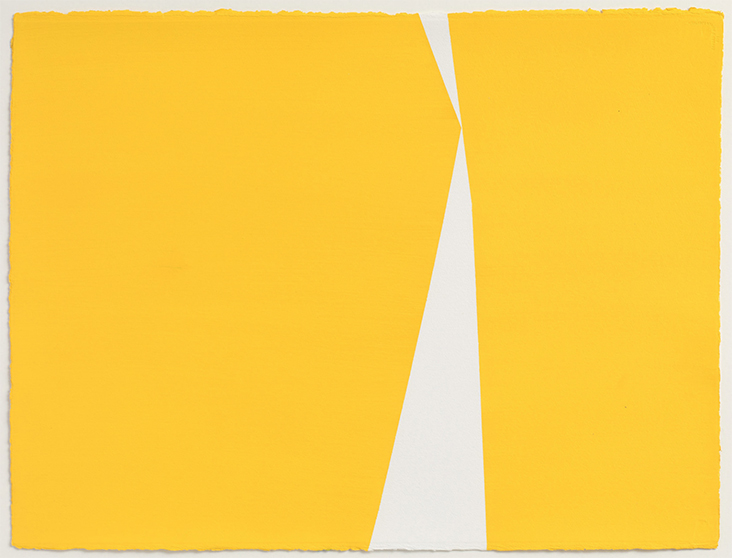

“What did I love? What was it that meant the very most to me inside my very own self? The fields and trees and fences and boards and lattices of my childhood rushed across my inner eye as if borne by a great, strong wind.”

Memories colour Anne Truitt’s art, as past experiences become towering columns of coloured light. Like many women artists Truitt found success later in life, steadily building a career as a leading Colour Field sculptor while simultaneously raising her large family. Along with Agnes Martin she is one of only a few women associated with the Minimalist school, yet hers was a poetic, internal language of subtlety and personal experience that set her distinctly apart from her peers, as she explained, “I have never allowed myself, in my own hearing, to be called a Minimalist. Because Minimalist art is characterised by nonreferentiality and … I’ve struggled all my life to get maximum meaning in the simplest possible form.”

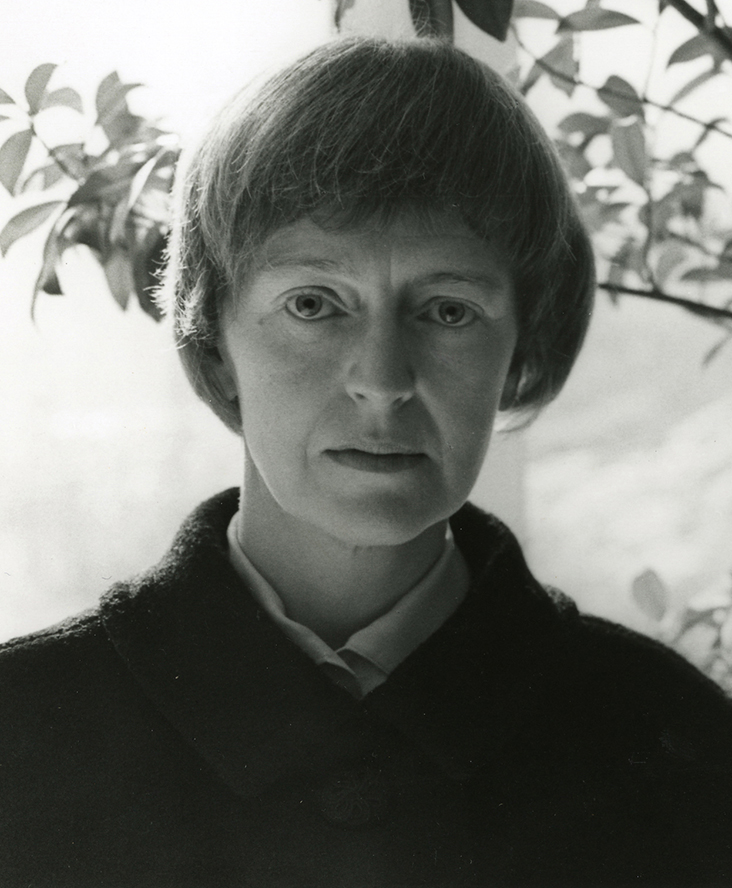

Born Anne Dean in 1921 in the coastal town of Easton, Maryland, the foundations for Truitt’s future career were already being laid. Her childhood was a free and happy time as the artist’s mother left Truitt and her two younger twin sisters to roam freely. Truitt was endlessly fascinated by the shapes and colours around her, later writing in her biography, “… and so it was with the little town of Easton, on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, an orderly scattering of houses, mostly white clapboard, so small that even on my short legs I was able to encompass the town’s dimensions.”

Truitt developed short-sighted vision in the fifth grade, which she came to credit for her innate sensitivity to colour, recalling, “I lived in a world composed of light and colour and shape, which I did not see, but which I had to intuit…” adding, “…because I couldn’t see, I was forced to develop my kinaesthetic sense to what may perhaps be an unusual acuity.” The initial contentment of Truitt’s childhood was shattered when the Great Depression hit, just as she was turning 12. Her family’s income took a knock and as a result her father became an alcoholic, while her mother developed chronic health issues. In the years that followed the family sought a fresh start in Asheville, but Truitt never truly forgot the unique colour and light of the Eastern shore. She was also burdened with a new level of adult responsibility, becoming carer to both her parents and her younger twin sisters.

In 1939 Truitt began studying psychology at Bryn Mawr College, but her studies were cut short when she came down with a severe case of appendicitis from which she nearly died. She was devastated when doctors wrongly assumed she had become infertile, but believing she couldn’t have children for the next decade made her more focussed than ever on career. Truitt resumed her studies the following year – during a series of biology lessons an interest in drawing was awakened, as she remembered, “I found myself able – I was totally astonished – to draw…it was my first taste of picking up and moving into visual terms what I saw to be true.”

When Truitt’s mother was diagnosed with a brain tumour in 1941 Truitt regularly travelled back and forth from Bryn Mawr to Asheville by train to take care of her, but she died later that year, leaving a deep void in Truitt’s life. Such pain, Truitt would later discover, became what she called “…the ground out of which art grows.” Truitt graduated with a psychology degree in 1943 and was offered a funded PhD place at Yale University in Connecticut, but chose instead to search for hands on work. Her first job was in a psychiatric lab at Massachusetts General Hospital, where she worked by day in the psychiatric lab and by night as a nurse’s aide during the Second World War. There she witnessed the horrific after-effects of war on deeply traumatised individuals, writing “I was steeped in pain during those war years when we had combat fatigue patients in the psychiatric laboratory by day, and I had anguished patients under my hands by night…” Though these experiences rattled her to the core, she later described them as fundamental to the development of her artistic career, giving her a deep understanding of human psychology and suffering, commenting, “I honestly do not believe that I would be an artist now if I had not first been a nurse’s aide.” As a creative outlet, and perhaps an escape, Truitt read copious amounts of literature and wrote her own short stories and poetry in the little spare time she had.

In 1945 Truitt first explored sculpture, taking on a clay modelling course with a group of friends. A small spark had been ignited, as she recalled, “…something about it stuck in the back of my mind – some unspeakable satisfaction in my hands. And a kind of ease unique in my experience, some matching of myself with material…” Through a fellow friend on the course Truitt met James Truitt, an English graduate from the University of Virginia and the pair struck up a romantic relationship, marrying in 1947. By the time Truitt had moved to Washington with her new husband she had become disillusioned with psychiatry, feeling a strong urge to pursue a career in the arts.

It was sculpture, in particular that had drawn her in; she soon signed up for a series of classes at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Washington DC, making a series of small, figurative clay models. There she met and befriended the painter Kenneth Noland, who also shared a childhood connection to Ashville.

As her husband took on a journalism role with LIFE magazine Truitt travelled widely, visiting Dallas, Mexico and New York. During this time she took on various art courses, learning to draw from life and carve wood, striking up friendships along the way which would help forge her career in the future. The pair eventually settled for an extended period in Washington, where they became part of a wide society circle, partly through her husband’s journalism and through Truitt’s own canny charm, hosting dinner parties for prominent arts figures such as Marcel Duchamp, Clement Greenberg, Isamu Noguchi, Hans Richter and Dylan Thomas. Truitt also established a studio space with Mary Orwen and later Mary Pinchot Meyer, where she began experimenting with making life-size torsos out of cement, clay, metal and stone.

Memory first became a source of fascination when Truitt was asked by a friend to translate from French Germaine Bree’s book Du Temps perdu au temps retrouve: Introduction a l’oeuvre de Marcel Proust (Marcel Proust and Deliverance from Time), which she says, “…set a kind of spine along which my thought has developed ever since.” As her practice developed she began exhibiting and selling her figurative sculptures in the mid-1950s.

Much to her surprise, Truitt became pregnant with her first child in 1955, and would go on to have a further two children in the following years. The family moved to San Francisco in California, where Truitt worked from home while raising her young family, making a series of clay constructions influenced by early Mexican art forms and producing hundreds of drawings in limited colours of black, brown and pink on old sheets of newsprint.

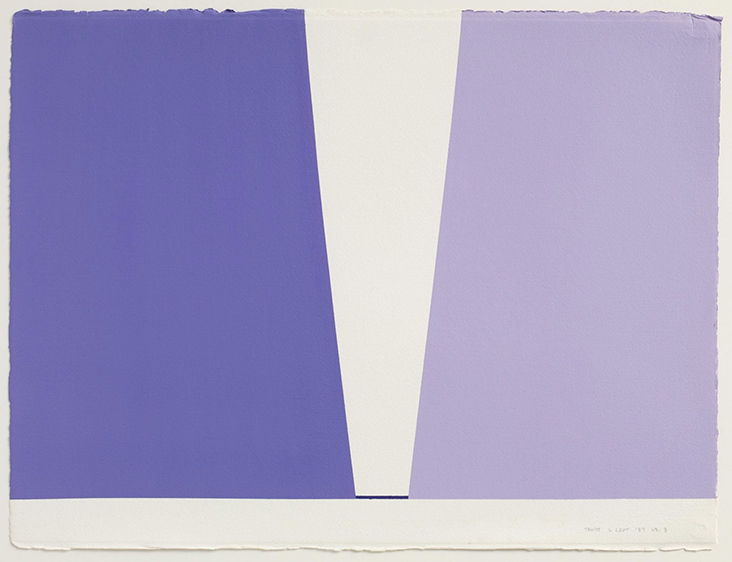

By 1960 Truitt was forced to move back to Washington again, following her husband’s new role at the Washington Post. Truitt continued to make work and socialise with other artists; during a visit to New York with her friend Mary Meyer she experienced something close to an epiphany after seeing the abstract Colour Field paintings of Barnett Newman, Ad Reinhardt and Nassos Daphnis at the Guggenheim Museum, who opened up to her the conceptual possibilities of colour. She reflected, “The works revered my whole way of thinking about how to make art … I was so excited that night in New York that I scarcely slept. I saw too that I had the freedom to make whatever I chose.”

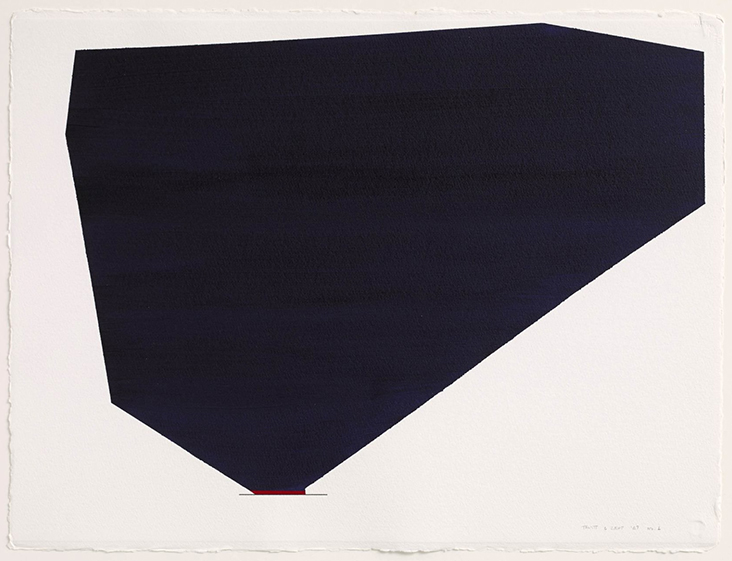

On her return to Washington she channelled her energy into a new body of work made from painted wood, including First, 1961, appropriately titled to denote its importance as the start of a new chapter, based on the picket fences of her childhood, yet made mysterious and human with minute differences between each post. Further works became vertical columns resembling fencing, tombstones, pillars and standing human bodies, which were slowly painted in dense, carefully applied layers of paint, including Knight’s Heritage, 1964. This relationship between refined geometry and memory would come to occupy the rest of her career.

Truitt’s friend Kenneth Noland invited renowned critic Clement Greenberg to see her new work, who in turn persuaded gallerist Andre Emmerich to give her a solo show at his gallery on 57th Street in New York, which was well received, with rave reviews in several leading art journals. Just as success seemed within her grasp, Truitt’s husband took a job in Japan and the whole family followed, relocating for the next three years. Truitt was deeply unsettled by the move, which ripped away her sense of place and belonging as well as pulling apart the artistic language she had spent years developing. Though she tried to find some solace through art, making painted aluminium sculptures including Sea Garden, 1964, much of the work from this time was later destroyed. She wrote, “I lost touch with myself. Deprived of my own inner certainty … I no longer enjoyed the effortless flow of intuitive insights which had sustained me from 1961 to 64.” Two years after returning, it seemed their marriage couldn’t recover and the Truitts divorced in 1969, leaving Anne in sole charge of her three children. She bought her own family house in Washington and remained there for the rest of her life. Reflecting on the duality of being both mother and artist Truitt concluded, “I worked between carpools and buying food and cooking and whatever else I had to do. I lived an outside life, but really I was living an inside life.”

Teaching at the University of Maryland allowed Truitt to support her family and just about find traces of time to keep developing her art. She was a hugely popular professor, who brought multiple interests in psychology, art history and literature into her art classes, remaining there for the next two decades. In her inspirational lessons she taught others, “By keeping on being what we most intimately are, we can continually redefine ourselves so that we become what we have not been able to be. If we live this way, we surprise ourselves.”

Following her return to the United States the relief was almost palpable in her art, as colours became lighter and brighter, expressing the fresh, breezy light embedded in her inner psyche. Columns often rested on recessed plinths as if floating in the air, as seen in A Wall for Apricots, 1968, while oblique references to landscape were made through tonalities of light, space and colour, illustrated by Breeze, 1978. Writer John Dorsey observed, “If one could unwrap the colour and put it flat on the wall, the verticals and horizontals of landscape would become even more obvious.” Truit also likened this three dimensional liberation of colour to the freedom she had found within herself, to express who she truly was, writing, “As I worked along, making the sculptures as they appeared in my mind’s eye, I slowly came to realise that what I was actually trying to do was to take paintings off the wall, to set colour free in three dimensions for its own sake. This was analogous to my feeling for the freedom of my own body and my own being, as if in some mysterious way I felt myself to be colour.”

Greenberg championed Truitt’s art as her reputation steadily grew, and she became recognised as one of the leading Washington Colour School artists alongside painters Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis. Aligning her with the advent of the American Minimalist School, an attribute that has often been written out of art history, Greenberg wrote, “If any one artist started or anticipated Minimal Art, it was she.”

Alexandra Truitt, Roseanne Hill, Anne Truitt, Julia Hill and Mary Truitt Hill / Washington, D.C. / by Mariana Cook

Truitt continued to advance her ideas on abstraction, producing a body of two dimensional work in her later years, including vast beds of colour on canvas and smaller, more intimate works on paper. In 1984 she published Daybook, a sensitively observed, intimate journal chronicling the wrestle between motherhood and an artistic career, reflecting, “It’s extremely difficult and you have to make sacrifices … You can’t have it all. You can’t. In a way, you can’t have much of a personality or anything because everything has to go into your work.”

Following her death in 2004, Truitt has become closely associated with American Minimalism, although during her lifetime she was at pains to point out her distinction from this group, who were influenced by her ideas, but a step apart, writing, “I think … the artists who became Minimalists took off from the look of my work, but missed the point of it – that point being the delicate fulcrum between the gravitas of discipline in the form and the intensity of the emotion in the colour.”

The emotional content of her work, and the social status she had as a woman and a mother, set her somewhat apart from the leading male artists of her day, and still do to some extent today as the history of Colour Field and Minimalist art is dominated by male voices. But the resonant, emotional properties in her art have influenced a whole generation of Post Minimalists since, many of whom continue to expand on her legacy today, bringing aspects of ordinary life into geometric, abstracted forms, including Roni Horn, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Rachel Whiteread. “Artists have no choice”, she reflected in her later years, “but to express their lives.”

Feature Image: Anne Truitt installation view

One Comment

Eva Hudkins

I discovered Truitt’s wonderful journal Daybook long ago and I’ve made sure to have it on my bookshelf ever since to re-read from time to time. Although I enjoyed her art, I can’t say I understood it until I read your article. Rereading Daybook now will be a real treat. Thanks for your article.