Eileen Agar: Monsters and Angels

“Paintings … germinate like a seed; in the dark soil and recesses of the living coral of the mind… They grow like a plant, slowly putting out shoots, they need pruning, meditating on, while the roots grow in the dark.”

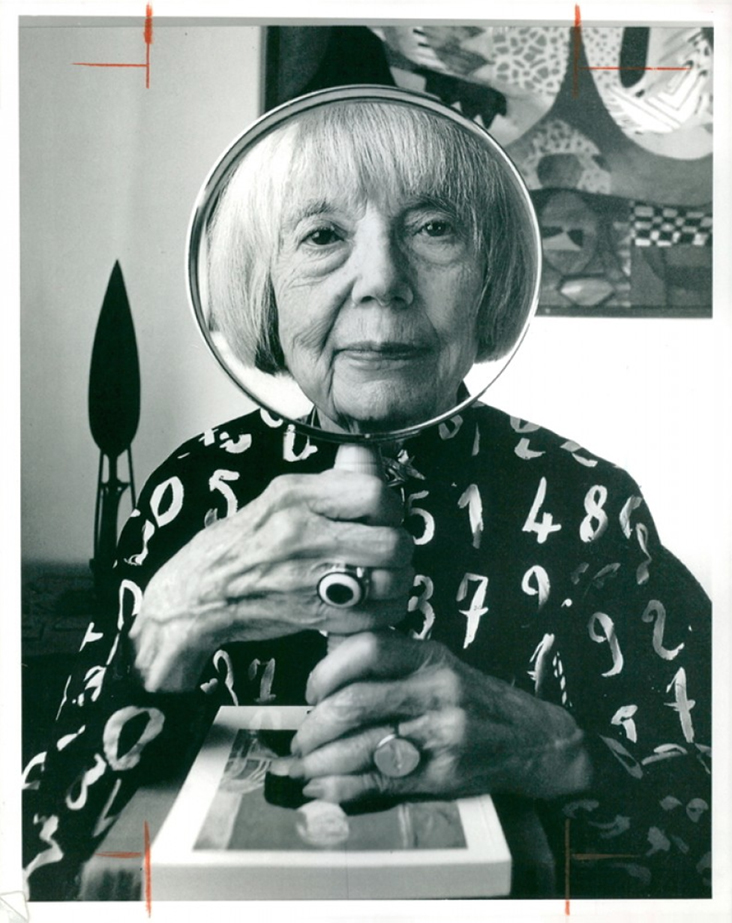

Eileen Agar was a free spirit, weaving her vibrant and endlessly experimental life into art. Her fluid, organic forms seamlessly morphed into painting, sculpture, collage, photography and many more media as she worked tirelessly into her 90s. She was one of the most daring and influential artists of her generation, yet as only a handful of women associated with Surrealism in her generation her career has often been defined by the men she knew, rather than who she was. Much like the women Surrealists working around her, the work she made envisioned a world where gender boundaries were indivisible and patriarchal oppressions melted away. There was also a distinctly psychological element to her work which moved beyond the sexualised bodies male Surrealists were fixated on, delving into the depths of the human subconscious, as she reflected, “The importance of the unconscious in all forms of Literature and Art establishes the dominance of a feminine type of imagination over the classical and more masculine order.”

Agar was born in Buenos Aires to a wealthy family of expatriates. Her Scottish father had established a successful business in windmill and irrigation systems in Argentina, while her mother was the American heir to a biscuit company. With a wild, great desert just beyond them nature could be a sublimely destructive force, as Agar recalls in one harrowing incident, “… a plague of locusts … descended on the whole countryside, and ate up everything, every little bit of leaf or anything … and we all used to have to go out with …carpet mats … to try and beat them down, because you could see them coming over in thousands, and it was most horrifying, and really disgusting. They were awful creatures…”

Amid the chaos Agar also found immensurable beauty, remembering, “In summer … everything was beautiful … and you could go into the garden and pick peaches, and nectarines, and anything you wanted… it was a very beautiful country…” Agar’s family made regular trips to London and Agar’s mother would dress flamboyantly in feathered hats, which would come to inform Agar’s art as an adult. At the age of six, Agar’s parents sent her to a British boarding School, later encouraging her to attend a finishing school in Paris, hoping she would marry well and continue the family lineage of wealth and security, but it soon became clear the rebellious young Agar had other ideas. She began studying art at the conservative Byam Shaw School of Art in Kensington, which she soon left to attend the more progressive Leon Underwood’s Brook Green School of Art in Hammersmith.

Spurred on by her newfound freedom, Agar moved on to study at London’s Slade School of Fine Art, graduating in 1924. At the Slade Agar soon realised the societal limitations placed on young women, as she explains, “…most men thought, ‘Oh well, the women will get married and have children, and they’ll forget about art’ … that’s why I decided I’d never have children. I thought, ‘You can’t do both.’” Agar was also determined to not be known as “a painter with rich parents,” moving away from her parents and setting up her own tiny studio in Kensington Square, while living off a small family inheritance.

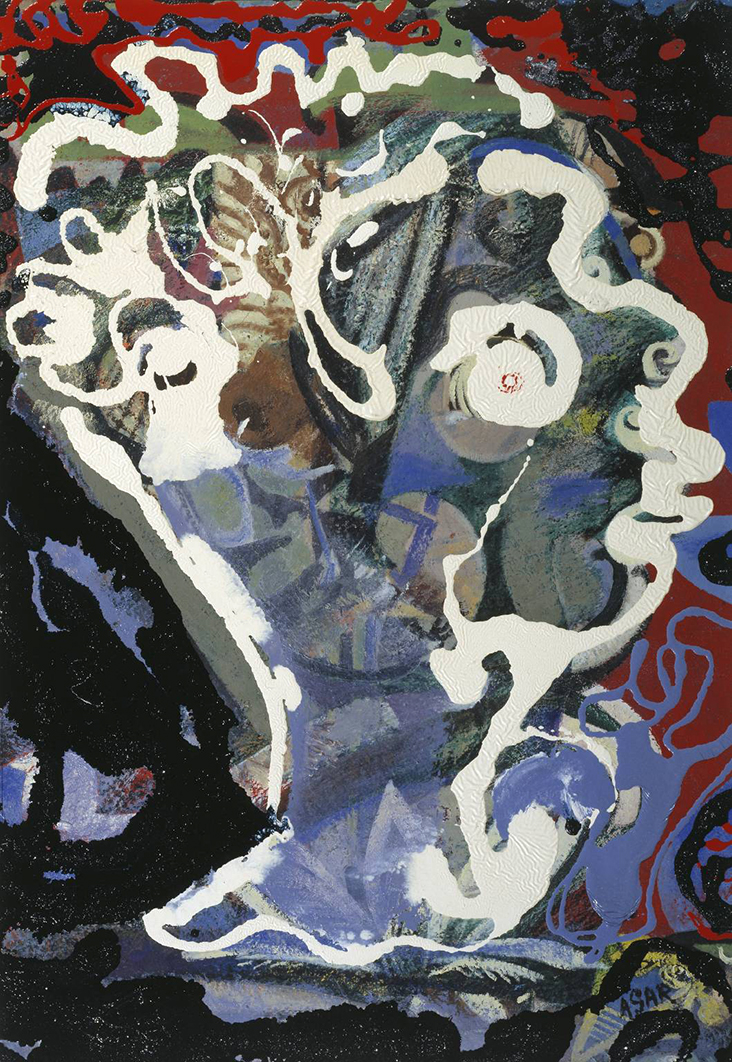

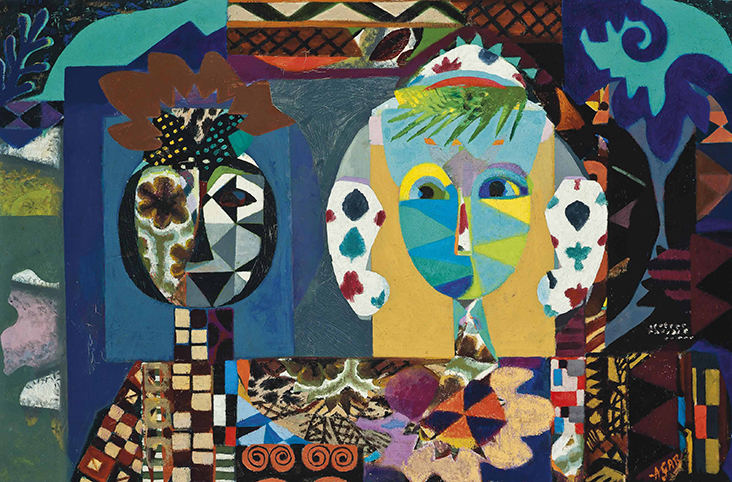

By the following year Agar had eloped with her fellow Slade student Robin Bartlett, much to her parent’s dismay, but the marriage was short lived, ending in divorce four years later. Agar soon ran away to Paris with her new lover, the Hungarian writer Joseph Bard, who she travelled with widely around Europe for the next few years. Eventually Agar settled with Bard in Paris, where she studied painting with Czech artist Frantisek Foltyn, who encouraged her towards a more abstract language. She also enmeshed herself with the burgeoning avant-garde circles who were practicing forms of Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Surrealism. Her paintings such as Three Symbols, 1930, Movement in Space, 1931, and Modern Muse, 1931, revealed the influence of modern Parisian art with abstracted, organic forms resembling nature, and a deeper level of symbolism suggesting a connection to the inner human psyche.

When Agar and Bard relocated to London in 1930 they worked together on the avant-garde literary and artistic magazine The Island, where Agar’s illustrations were instrumental in bringing Parisian Surrealism to Britain. In London Agar befriended Britain’s leading artists including Henry Moore and Paul Nash, who invited her to join the London Group, a transgressive collective who rebelled against the Royal Academy’s traditional styles of art.

Agar’s reputation was growing, and she held her first solo exhibition at London’s Bloomsbury Gallery in 1936, where she exhibited a series of collages, sculptures and paintings featuring found objects. As an avid collector, Agar was known for scavenging fields and beaches during her holidays with Bard, collecting unusual ephemera including starfish or rams’ horns, items which could be brought together in new and fantastical ways into sculptures, as she reflected, “I’m very fond of putting different objects, different things, together to make a totally new object.” Her two dimensional work demonstrated the same ‘cut-and-paste’ approach, often featuring low relief or protruding elements assembled to create a new kind of reality, closer to dreams and the subconscious mind.

Following the success of her solo show Agar was the only woman to be selected for the International Surrealists Exhibition at London’s New Burlington Galleries in the same year, securing her fame in a way she had not anticipated. She was painfully aware of the inequality around her, noting, “… in those days, men thought of women simply as muses, they never thought that they could do something for themselves, and I’m always astonished how they let me in to the 1936 exhibition…” Agar signed the British Surrealist Group’s manifesto in the same year, as her work took on international stature, appearing in Surrealist exhibitions in New York, Tokyo, Paris and Amsterdam, where she was respected worldwide for her lyrical, uncanny language.

In 1936 Agar visited Brittany, famously photographing the bizarre forms of the Ploumanac’h Rocks in stark lighting, lending them the quality of nightmarish monsters. Continuing to travel widely in the following years, Agar went on raucous group holidays and attended wild parties with fellow British and French Surrealists. In one photograph taken in Mougins in France, Agar is seen wearing a transparent dress, nodding towards the group’s outrageous antics. Her flamboyant clothing extended into art as a series of ‘Surrealist hats’ featuring spiky, monstrous sea creatures and fish bones including Ceremonial Hat for Eating Bouillabaisse, 1936, bringing her Surrealist eye into the realms of fashion, an item described by the V&A Museum as “one of the most unusual objects to come to the Textiles Conservation Section.”

Agar began producing a series of semi-figurative sculptures in the later 1930s. Around this time she produced a modelled bust in clay of Bard’s head, which later evolved into her iconic sculpture Angel of Anarchy, 1936-40, a strange, hybrid creature that seems half-bird, half man. The feathers were inspired by the hats Agar’s mother wore, while African beads and jewellery nod towards her fascination with ethnographic art forms. Dr Patricia Allmer delved into the work’s underlying meaning, describing the sculpture as “enacting a man’s becoming a woman.” Allmer goes on to describe the symbol of the angel as a Surrealist woman’s motif, one that represents “hybridity and becoming”, encapsulating a collective desire to overcome patriarchy and find true independence. The head’s masked quality could be read as men’s “blindness” towards women’s immense creativity, while the dissident title reveals Agar’s inherently rebellious spirit. Political allusions were also made, with the term ‘anarchy’ linking Agar and her fellow Surrealists to the Spanish Anarchists, who they strongly supported at the time.

In 1940 Agar married Bard, despite her numerous infidelities in the years they had been together. During the war, Agar’s art practice and wild antics took a backseat as she took on various roles to support the British war effort, working as a canteen assistant, cleaner and fire watcher. By the end of the war Surrealism had become a national institution, with Agar’s reputation cemented in history. Agar exhibited less frequently after the war, particularly when Bard’s health was failing and she became his full-time carer until his death in 1975. Yet she never stopped working, finding a new passion for acrylic paint in her later years. Her earlier forays into fashion also led her to model dresses for Japanese designer Issey Miyake in 1986, where she described an extension of Surrealist ideas in “…new masks, which released the wearer from him or herself.” After a retrospective exhibition in 1987, Agar published her memoir, A Look at My Life, 1988, a fascinating insight into bohemian pre-war Paris and London, released just three years before her death in 1991, age 92.

Today Agar’s work exists in museums and collections around the world, and she is widely recognised as one of the most tenacious and daring individuals associated with the movement. In recent decades various exhibitions have celebrated women’s contribution to Surrealism, which is far more extensive than post-war accounts would have it, placing Agar’s work at the helm. This is important work that disentangles Agar as a leader alongside, rather than behind, the men around her.

Agar was a true trailblazer, who showed countless contemporary artists how life could become one with art, influencing today’s male and female artists alike, including Tracey Emin, Grayson Perry and more recently Tacita Dean, who celebrates her “Levity, mirth and re-imagination.” Agar’s penchant for wearable art has infiltrated the realms of fashion, shaping the fantastical creations of Hussein Chalayan, Mary Katrantzou and many more. She encouraged a spirit of free play, where unchartered depths of beauty and horror in equal measure could unfold, writing, “In play the mind is prepared to accept the unimagined and the incredible, to enter a world where different laws apply, to be free, unfettered, and approach the divine.”

Feature image: Bernard Shaw Feeding the Birds / Eileen Agar / 1934

4 Comments

Pingback:

Marrying Contemporary Art with Dopamine Dressing Themes - goodvibe.lifeTrish Jakielski

I love this series of articles on artists – especially the focus on women . Thank you for the overview of these amazing women! I see fashion and rugs and all kinds of things in these works – so I see the tie to your wonderful products. But mostly I appreciate the emphasis you place on opening our eyes to works of women artists.

More, more….!

Mary j Hughes

A great article about a fascinating woman.

I’ve enjoyed reading this wonderful series and I look forward to more.

Thank you!

Cat Tillotson

Well done, Rosie. Thanks for another insightful post!