Rachel Ruysch: Flower Power

Juriaen Pool and Rachel Pool-Ruysch Family portrait with flower still-life in the making / 1716 / Stadtmuseum Düsseldorf

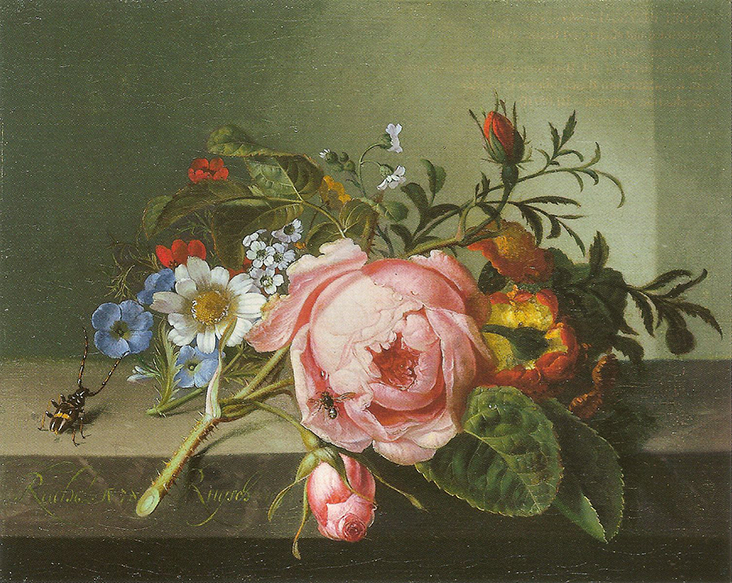

Rachel Ruysch’s intricate, exquisitely detailed paintings are hidden worlds of wonder and discovery. Beneath lavish, gorgeously decadent flower and fruit displays lie the darker side of nature, as petals decay and reptilian insects emerge from the shadows into the glistening light, threatening to devour them. Like many women artists of the Dutch Golden Age Ruysch was restricted to domestic, decorative subjects, yet she rebelled with a quiet revolt, tipping beyond beauty into realms of the uneasy and macabre. With her virtuoso skill and quiet symbolism Ruysch rose to prominence as Holland’s unrivalled pioneer of flower painting, commanding high prices and international fame within her lifetime. Today she is one of the most documented female artist of her time, one who juggled huge family responsibilities with an unrelenting drive to succeed. Yet despite this, her name has yet to command the same authority as her male contemporaries today. Alex Bell, head of Sotheby’s Old Master paintings reflected on the enormity of her career and the respect she deserves, celebrating her as “the most important female still life painter in western art.”

Ruysch was born in Amsterdam in 1664 to a wealthy, intellectual and artistic family. Her father, Frederik Ruysch, was one of the city’s most prominent scientists and he often called upon his young daughter to help him catalogue his vast archive of rare natural history specimens. He famously assembled one of Europe’s finest Curiosity Cabinets, a fascinating showcase displaying an array of immaculately preserved specimens from around the world including birds, butterflies and plants. When he became head of Amsterdam’s botanical garden his knowledge of plants increased tenfold, giving him an in depth understanding which he would pass on to his intellectual and artistic young daughter.

Ruysch’s father nurtured his daughter’s natural flair for art from an early age, encouraging her to create careful studies from his extensive collections or based on his detailed scientific illustrations. It was the norm for female artists in the 17th century to take on an apprenticeship under the tuition of their father in this way, but more unusually, Ruysch’s talent showed such promise that she earned an apprenticeship outside her family with the renowned, famous still life painter Willem van Aelst at the age of 15, in 1679. She learned the tools of the trade from assisting him with his work, while he taught her how to arrange flowers to appear spontaneous and haphazard, adding dynamic pictorial depth, energy and movement.

Ruysch soon moved beyond van Aelst in her own paintings, working with a lighter, brighter palette and exploring the more decorative possibilities of still life. By the time she was 18 Ruysch was already selling her work to independent buyers, earning a modest income which would grow considerably over the next seven decades. Bell points out how unusual it was for a woman to achieve such a reputation during the era, writing, “At a time when few women ventured into the male dominated world of professional painting, let alone found success in the field, Ruysch emerged as one of the greatest artists, of either gender, ever to have specialised in the genre of still life painting.”

Like many aspiring women artists of the 17th century, Ruysch was pigeonholed by Dutch society from the start of her career. Women were pushed towards still life subjects for several reasons – on the one hand it was thought women had more powerful skills of observation than men and it was expected that they would focus on close studies of the natural world. The genteel subject of still life also had a non-threatening nature, deemed more appropriate for the ‘fairer’ sex. Women were expected to spend their time in the domestic arena tending to the home, where still life was an easily accessible subject. Landscape or figurative subject matter required travel, anatomical study, live models or time in the public arena alone, all of which were forbidden for women.

Not one to sink into the background, Ruysch embraced the growing cultural interest in flower painting and made it her own. She befriended various well known flower painters around her in Amsterdam who had found commercial success, including Jan and Maria Moninckx, Alida Withoos and Johanna Helena Herolt-Graff, as well as the local plant collectors Jan and Caspar Commelin, sharing ideas about art, botany and nature which would continue to inform her minutely detailed and painstakingly accurate studies. Curator Betsy Wieseman observes the incredible skill she demonstrated, even early in her career, commenting, “One of Ruysch’s most beautiful characteristics is her ability to render all these different textures and her use of light and shadow to bring the flowers towards us, to really create an illusion of three dimensions within the bouquet.”

Flowers in a Vase, is one such example, made in about 1685, not long after she graduated from van Aelst’s workshop. Lush, vibrant flowers bristle, shift and move towards us and our eye is drawn to a soft pink flower in the centre, whose petals seem to billow with the plump softness of human flesh. Moving beyond the purely decorative nature of her subject, Ruysch includes caterpillars, spiders and a grasshopper wriggling out from the darkness into the light. Here they become symbols representing the natural and gritty cycle of life, while nodding towards the vanitas tradition of painting, highlighting the fragility of life’s ‘vanities’ and the brevity of human existence. Writer Mark De Vitis writes, “Insects, with their short lifespans, speak to the fleeting nature of time. Insects also consume or destroy flowers. Their presence here calls into question the viewer’s initial delight in encountering the carefully manufactured loveliness of the work.” In early works she also focussed on woodland scenes as influenced by Otto Marseus van Schrieck, setting her floral arrangements on earthy bracken or tree trunks to lend them a dirtier landscape quality, particularly when overrun with insects.

Ruysch had already established her career when she married the portrait painter Juriaen Pool at the age of 29. Remarkably she went on to have 10 children with him, all the while continuing to maintain a career that would eclipse that of her husband. When her children were young, the broad ambition of her work took a backseat as she focussed on smaller, simpler painted studies.

Unlike the majority of women artists around her, marriage and children did not seem to present an insurmountable obstacle for her, partly because the sales of her work allowed her to finance childcare. Weiseman also points out that painting may well have become a silent refuge for her, commenting, “I think she was unique, and I often wonder whether it was because, or in spite of the fact that she had ten children that she became such a successful artist, maybe her studio was her refuge.” In 1708, Ruysch’s outstanding abilities even won her the role of court painter for Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine in Dusseldorf, who she produced work for in Amsterdam and had shipped over to him.

As Ruysch’s children grew, so, too did her practice and her success as she responded intuitively to the cultural environment around her. The Netherlands were prosperous in the late 17th and early 18th century, with a thriving market for specialist art. The country also became one of the highest importers of new and exotic plants from around the world, leading to a boom in the Dutch horticultural and botanical industries. Across Europe flowers became powerful symbols of luxury and wealth and their sale prices rocketed, with tulips so in demand they were selling for as much as a small house. Ruysch’s paintings tapped into and reflected the absurdity of this “tulip mania”, with decadent, abundant floral bouquets including Flowers in a Glass Vase with a Tulip, 1716, which reveals an even greater sense of overwhelming mass than her earlier works, with flowers reaching outwards and upwards into deep chiaroscuro space, undercut with teeming insects beneath their decorative surface. She also made dramatic studies of glossy, fleshy fruits and vegetables that sparkle with light, surrounded by encroaching insects.

Flower arrangements became more ambitious, adventurous and imaginative as she deliberately combined blooms from different seasons together, lending her paintings an unreal, magical property. The religious symbolism of flowers also came to colour her paintings, as seen in Still life with Flowers in a Glass Vase, 1716, which makes reference to the Christian trinity with flowers in groups of three, while white poppies, known for their associations with sleep and death, refer to the crucifixion and morning glory, with its ability to open from a dormant state, to the resurrection. Roses also featured frequently in her work, most likely relating to her family crest which was a blue rose with five petals.

Ruysch lived a long and prolific life, producing more than 250 paintings over seven decades for some of Europe’s most important patrons, achieving widespread fame and international recognition as Dutch writers called her “Holland’s art prodigy” and “our art heroine.” In 1750 a collective of poems written by various poets over the decades was published, titled, Poems for the Excellent Painter Mistress Rachel Ruysch.

But in historical renditions of the Dutch Golden Age it is the male voices who have risen to the top, while the strength of Ruysch’s legacy has almost been erased, despite the fact that her paintings often sold for higher prices than Rembrandt’s work. This may, in part be due to the decorative subject matter she was forced to pursue. It is only in recent times that historians have begun to fully appreciate the layers of symbolism beneath the surface of her work, which was a powerful commentary of the time she lived in, pointing towards the deeper values of Christianity and spiritual tradition, as well as the frailties lying beneath societal constructs.

The National Museum of Women in the Arts has been instructive in bringing Ruysch’s paintings into the 21st century, displaying her paintings alongside some of today’s leading contemporary artists whose practices align with hers, including Sam Taylor Johnson, Kiki Smith and Joan Mitchell, in order to demonstrate, as director Susan Fisher Sterling comments, “…women artists, historical and contemporary, are often adventurous, inventive and subversive when dealing with nature in their work.”

Norbert Middelkoop, curator of paintings, prints and drawings at the Amsterdam Museum sees Ruysch as a beacon of light who is more fascinating than ever today, as history is slowly rewritten to include forgotten voices of the past: “A painting by Ruysch can always count on attracting special attention, both because of the consistently high quality of her flower still lifes and because of the remarkable fact that Ruysch, as a woman painter, gained such an outstanding reputation in a professional world dominated by men.”

5 Comments

Barbara Rodts

So enjoyed this interesting article. Her art is mesmerizing. Keep up the good work.

Vicki Lang

thank you for writing about such a strong woman who out painted most men.

Martha Maria-louisa

Thank you so much for the post.

I’d recommend a listen to the BBC -4 Programme, Moving Pictures; a segment of which was dedicated to this artist.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07wpgjm

Please continue these wonderfully informative postings. I so much enjoy them.

MM-L

Melynda Huskey

I enjoy these posts calling attention to the work of women artist so much! Thank you for this series, and for putting our work as craftspeople in the context of a long history of women making art despite constraints.

Gaye Elder

I truly enjoy these articles. I was not aware of this artist and am happy to make her acquaintance. I am not, of course surprised at her loss of reputation. As a 76 year old woman myself, I’ve seen and heard the story of many women’s shift into obscurity.