Barbara Hepworth: Spiritual Sculptor

Hepworth in the Mall Studio, London, 1933. Photograph by Paul Laib. © The de Laszlo Collection of Paul Laib Negatives, Witt Library, The Courtauld Institute of Art, London

“…the strokes of the hammer on the chisel have to be in time with your heartbeat or pulse.”

Barbara Hepworth’s name is synonymous with smooth, monolithic forms resembling human bodies or careworn sea-lashed rocks. Today she is recognised as one of Britain’s foremost Modernist sculptors, part of a generation exploring post-war abstraction with a hard-won, hand-crafted intimacy. At the time she was one of few women sculptors to rise the ranks in a male centric field, yet she resisted any attempts to label her as a feminist, arguing simply, “art’s either good or it isn’t.” After five decades of carving, tapping and chiselling she tunnelled her place into art history through sheer, hard graft. But beneath the physical demands of her tactile art there was a deeply spiritual strand, one that breathed human energy and life into static materials, merging visceral material with contemplative, cerebral thought. She wrote, “Vitality is not a physical, organic attribute of sculpture – it is an inner spiritual life.”

Barbara Hepworth with her cat Nicholas and Curved Reclining Form (Rosewall) 1960–2 in a photograph taken by Ida Kar in 1961, © National Portrait Gallery, London

Hepworth was born in Yorkshire’s Wakefield in 1903, surrounded by the drama of steep cliffs and rugged, windswept grasslands. On long car trips around the Yorkshire countryside with her father she developed a fascination with the landscape, remembering back, “All my memories are of forms and shapes and textures. I remember moving through the landscape with my father in his car and the hills were sculptures; the roads defined the form. Above all, there was the sensation of moving physically over the contours of fullness and concavities, through hollows and over peaks – feeling, touching through mind, hand and eye.”

These early experiences would come to shape her art as an adult, as she reflected back, “I think what we have to say is formed in childhood, and we spend the rest of our lives trying to say it.” Hepworth grew up in a middle class, egalitarian household, yet her early aspirations were to be like her intellectual father rather than her socialite mother. As a young adult Hepworth studied fine art at Leeds School of Art from 1920-21, where she was quietly tenacious and determined, believing “you have to have a passion, an obsession to do something.” Her passion, she soon discovered, was for sculpture.

Barbara Hepworth working on Oval Form, Trezion, 1963, Photograph by Val Wilmer, Courtesy Bowness, Hepworth Estate

At Leeds Hepworth met Henry Moore, developing what would become a lifelong friendship fuelled by rivalry, particularly when both artists went on to study sculpture at the Royal College of Art in London. During a year’s travel scholarship to Italy Hepworth visited Rome, Siena and Florence, where she was entranced by the uplifting displays of light and shadow around her, describing it as “the wonderful realm of light – light which transforms and reveals, which intensifies the subtleties of form and contours and colours, and in which darkness – the darkness of window, door or arch – is set as an altogether new and tangible object.”

In Italy Hepworth fell for the British sculptor John Skeaping and the pair married in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio in 1925. They began their early married life together in Rome where Hepworth learned marble carving techniques from Italian carver Giovanni Ardini, who taught Hepworth to respond with gentle, coaxing sensitivity towards the marble and its unique sensual properties, allowing light to caress its smooth, glossy surface. Nestling pairs of birds appeared in her early sculptures such as Doves, 1927, a reference to the pet doves she and Skeaping kept, yet perhaps also a nod towards the innocent, romantic union between Hepworth and her lover.

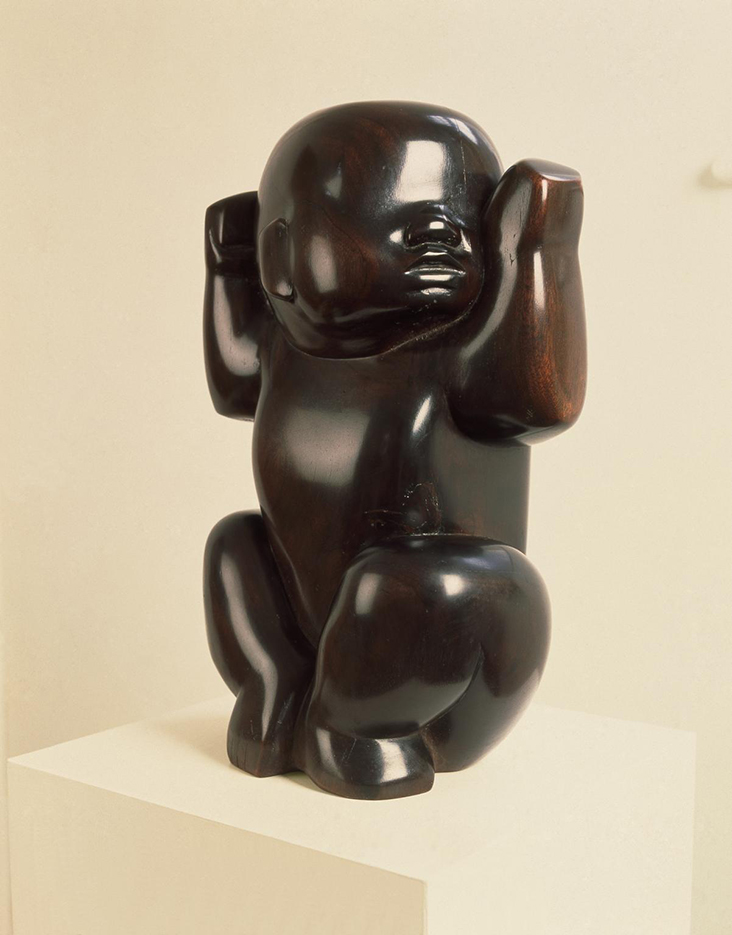

When Skeaping faced a series of health issues the pair returned to London in 1926. Three years later Hepworth gave birth to her first child, carving the tender sculpture of her newborn son, Infant, 1929 from polished Burmese timber, allowing the glowing warmth of natural wood to emulate an inner sense of intimacy and love. Though they often exhibited together, Skeaping was intimidated by Hepworth’s unflinching ambition and by 1931 he had had left her for another woman. Hepworth’s work shifted towards pierced sculptures, penetrated by large holes that allowed light all the way through, allowing room for both the negative and positive emotions she experienced to circulate around silky smooth, pure forms, both framing and punctuating the space around them.

Hepworth began a new relationship with painter Ben Nicholson in the following years, one that would lead to marriage in 1938. Together Hepworth and Nicholson established a home in Hampstead, North London, surrounded by a lively artistic circle, described by art historian Herbert Read as “a nest of gentle artists” including Hepworth’s fellow alumni Henry Moore. The bohemian group shared a fascination with reductive, abstract forms and pure, simplified colours, opening up a free interchange of ideas that would shape the direction of British art history. Both Hepworth and Moore became leading pioneers in Direct Carving, a process of working directly with chosen materials to allow a form to evolve organically and intuitively, rather than through preparatory models or plans. Hepworth believed resolutely in the “truth to materials” maxim promoted by sculptors including Constantin Brancusi, Jacob Epstein and Eric Gill, drawing out innate properties of surface, colour and light hidden within rough, natural materials including marble, wood and stone.

Barbara Hepworth in the Palais de la Danse studio, St Ives, at work on the wood carving Hollow Form with White Interior 1963 Photograph: Val Wilmer, © Bowness

When Hepworth travelled to Paris with Nicholson in the early 1930s she met and befriended some of the most pioneering artists of the age including George Braque, Piet Mondrian, Picasso, Constantin Brancusi, Jean Arp and Sophie Taeuber-Arp. The burgeoning forms of abstraction in the School of Paris had a profound influence on Hepworth’s practice, particularly the fusion between landscape and human form, giving her the confidence to delve deeper into the realms of abstraction. Following her visit to Paris Hepworth became an active member of the Paris-based artist collective “Abstraction-Creation,” while continuing to gain a reputation in the UK.

In 1934, when Hepworth gave birth unexpectedly to triplets, she was beset by practical and emotional demands, particularly since she had little money or help. Yet the role of motherhood was one she would come to embrace and integrate into her role as an artist. She asserted, “A woman artist is not deprived by cooking and having children, nor by nursing children with measles (even in triplicate) – one is in fact nourished by this rich life, provided one always does some work each day; even a single half hour, so that the images can grow in one’s mind.”

An even wider range of spirituality and emotion filtered into her increasingly abstract sculptures in the years that followed, which often referenced the close, familiar love and intimacy of motherhood. She also increasingly focussed on groups of three, as in the elegant Three Forms, 1935, in which smooth white pebble-like stones converse in a small, intimate grouping. As her children grew older Hepworth found childcare in a Hampstead nursery-training college, allowing her greater freedom to pursue the practical demands of her work. The 1930s were a hugely formative time as her sculptures became more streamlined and abstract. Alongside her mostly male contemporaries Hepworth strongly believed abstraction could offer a spiritual, intellectual and utopian freedom from the constraints of European fascism, though she was well aware that this field of exploration was dominated by male voices, writing, “Apart from being a woman, it has not been easy, always having great bears breathing down one’s neck!”

Like many Londoners, when the war broke out in 1939 Hepworth, Nicholson and their three children fled for the countryside, finding refuge in a friend’s small house in St Ives in Cornwall. For the first time in her adult life Hepworth was unable to make large sculpture, focussing instead on small models, drawings and studies, while juggling child-minding, cooking and growing vegetables for her family until her children received a boarding school scholarship the following year. All around her a lively community of war-time evacuees was forming as increasing numbers of creative voices congregated in the Coastal town.

‘Bicentric Form’ in the carving yard at St Ives, January 1950. Photograph: Studio St Ives. Copyright: Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

In St Ives Hepworth was fascinated by the white light of the landscape around her, while natural, weather worn, coastal shapes and colours infiltrated her work, often as abstract symbols of endurance and eternity. She also found the ideal setting to integrate her sculptures with the land, living out the human- nature connection that had fascinated her for decades. Hepworth bought a house and studio in St Ives in 1949 and she would spend the rest of her life here, facing the luminescent, aqua blue ocean. In Hepworth’s St Ives work there was, and still is, a wild, natural beauty echoing the forces of nature that countered the devastating destruction of war by providing some sense of hope and optimism. Situated amongst open stretches of land, her work has the permanence of prehistoric standing stones, speaking of human endurance and internal spirituality. Such profound artworks attracted a plethora of younger followers including Peter Lanyon, Roger Hilton and Terry Frost, who were all drawn to the St Ives Coastline, following in her footsteps with abstracted, weathered natural forms, and they joined her in establishing the Penwith Society of Artists in 1949.

Vertical Forms’ in the workshop in St Ives, September 1951. Photograph: Studio St Ives Copyright: Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

After the war Hepworth’s reputation continued to grow in unprecedented ways as she became an international art phenomenon. Though Hepworth had long felt cast in the shadows of her male contemporaries, particularly Henry Moore, in the 1950s her public visibility increased tenfold when her work was shown at the Venice Biennale in 1950 and the Festival of Britain in 1951. If her professional life was laying down roots, her personal life had hit the rocks – Nicholson left her in 1951, while in 1953 her first son with Skeaping died in a plane crash. Work took on a greater sense of urgency as a remedy to her troubled personal life and she became more determined and ambitious than ever, producing vastly scaled public art commissions for a range of international clients, as one friend observed, “she just worked so bloody hard.” To keep up with demand she began producing edition sculptures as casts in various metals, particularly for outdoor settings, making them more weather resistant. As her sculptures became increasingly abstract and simplified, she wrote, “There must be a perfect unity between the idea, the substance and the dimension.” Various accolades followed, including a series of honorary degrees, the CBE in 1958 and the DBE in 1965. She was also awarded with the Freedom of St Ives in 1968, to celebrate her enormous contribution to the small coastal town.

Barbara Hepworth at Trewyn Studio, 1961. Photograph by Rosemary Mathews, Courtesy Bowness, Hepworth Estate

Hepworth’s name is interwoven with St Ives today, where her studio and sculpture garden remain an enduring, worldwide attraction. The Hepworth Wakefield was established in the town where she was born, a fitting memorial to a place that had such a formative impact on her as a child. She has influenced countless artists, designers, architects and performers since including Linder Sterling, Peter Jensen and Rebecca Warren, who have all referenced her as a key influence in their creative practices, for the strength, spirit and timeless elegance of her art. Hepworth truly lived out her lifelong belief: “A sculpture should be an act of praise, an enduring expression of the divine spirit.”

Feature Image: Hepworth in Trewyn Studio, October 1949. Photograph: Studio St Ives. Copyright Barbara Hepworth © Bowness

Leave a comment