Mary Cassatt: A Modern Woman

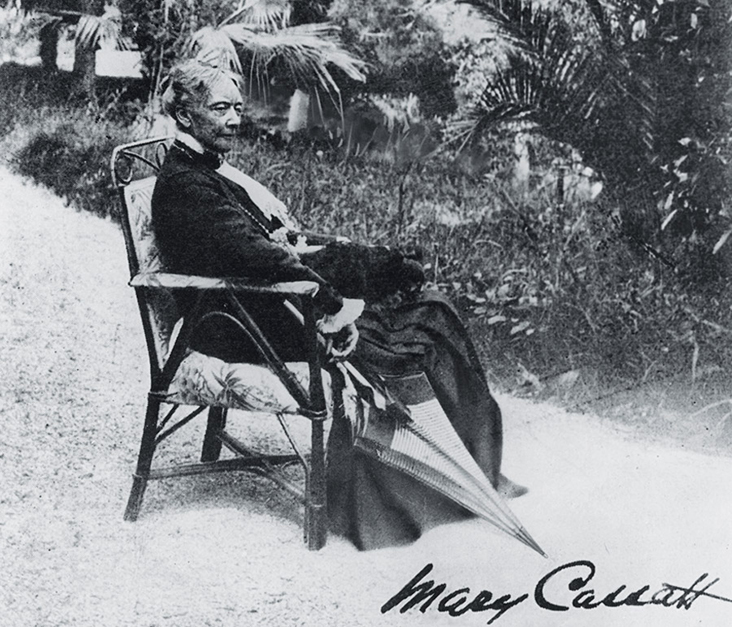

Mary Cassatt / 1913 / black and white photograph. Verso reads: ‘The only photograph for which she ever posed. Courtesy of Durand-Ruel.’ Courtesy: The Frick Collection, New York

“I hated conventional art. I began to live.”

Mary Cassatt was a painter’s painter, capturing her subjects with open, fluid brushstrokes loaded with energy and life. Rising to prominence in 19th century Paris, style was as radical as content, as bold brushstrokes and dazzling colours captured the minutiae of ordinary life with the rapid eye of a true Impressionist. Yet as a female painter surrounded by men her world view was bound to be different from her male peers, providing a vital woman’s perspective on modern urban living. Though history has tended to sentimentalise her art, particularly her many portrayals of women and children (often referred to as ‘modern day Madonnas’) there are depths of psychoanalysis beneath their apparent contentment, acting as astute observations on the roles women and young girls were expected to play. Professor and theorist Griselda Pollock notes, “Recognising her novel and intensely formal explorations of … subjectivity … we can … appreciate the symbolist interest in psycho-social complexities (she) shared with modernist writers and thinkers.”

Cassatt was born in 1844 to a wealthy family in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania. From a young age she revealed a desire to draw and paint, which her parents initially encouraged with extra art lessons. The family spent several years in France and Germany when Cassatt was a child, where Cassatt became fluent in both French and German, skills which would allow her the freedom to travel widely as an adult. In 1855 they returned to live in Pennsylvania, though the young Cassatt had already developed an infatuation with French art, particularly the progressive, Realist paintings of Gustav Courbet and Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot.

As a young adult Cassatt expressed a desire to be a painter, though her father was reticent, believing painting to be a dangerous pursuit that encouraged unwanted public attention from “the equivalent of trolls, who harassed and followed public figures, especially women.” Cassatt’s upper class status also made her an unlikely figure within the arts – it was almost unheard of for a society lady to become an artist. Against her parents’ wishes Cassatt began studying art in Pennsylvania before heading to Paris to study in the 1860s, where she would spend the majority of her adult life. During these years Cassatt travelled widely around Europe, copying great masterpieces by Correggio, Velazquez and Rubens, observing, “One does not need lessons. Museums are sufficient.”

Throughout the 1870s Cassatt was determined and prolific, establishing a studio in Paris and regularly exhibiting her paintings at the Paris Salon. French Impressionist Edgar Degas saw her work at the Salon in 1874 and was impressed, observing, “This is someone who feels the way I do.” Initially Cassatt found the artistic environment in Paris supportive and encouraging, writing, “women (did) not have to fight for recognition if they did serious work.” But in 1877 as her paintings became increasingly freer and less academic Cassatt was rejected by the Salon for the first time, and she developed a growing disenchantment with the staunchly traditional Parisian establishment.

Waiting in the wings, Degas had continued to follow Cassatt’s practice with interest as it became increasingly rebellious and painterly, and in 1877 he invited her to join the Societe Anonyme des Artistes Peintres, Sculptors, Engravers etc. (The Anonymous Society of Painters, Sculptors, Engravers), a group that would later become known as the French Impressionists. In Degas Cassatt found a kindred spirit – Degas had an American mother and both his brothers had married American women, and the pair even discussed travelling there together someday. The society had been established jointly by both men and women, and within the wider group Cassatt discovered a fertile, creative ground from which she could share and grow new ideas. Exhibiting regularly, her work took off in daring and adventurous new directions, as seen in her vividly coloured, expressively painted Little Girl in a Blue Armchair, 1878 as she realised, “At last, I could work with total independence, without worrying about the opinion of a jury. I started living.”

But even within this liberal, forward looking group, who called themselves “independents”, distinctions between men and women’s paintings became increasingly evident, not least due to societal restrictions barring women from access to certain areas of public life. Where men rebelliously painted the boys only sports clubs, bars, brothels or backstage theatre scenes, women were restricted from entering such places. Cassatt and her female colleagues, including Berthe Morisot, therefore captured a different, yet no less important slice of modern, Parisian life as seen through a woman’s eyes.

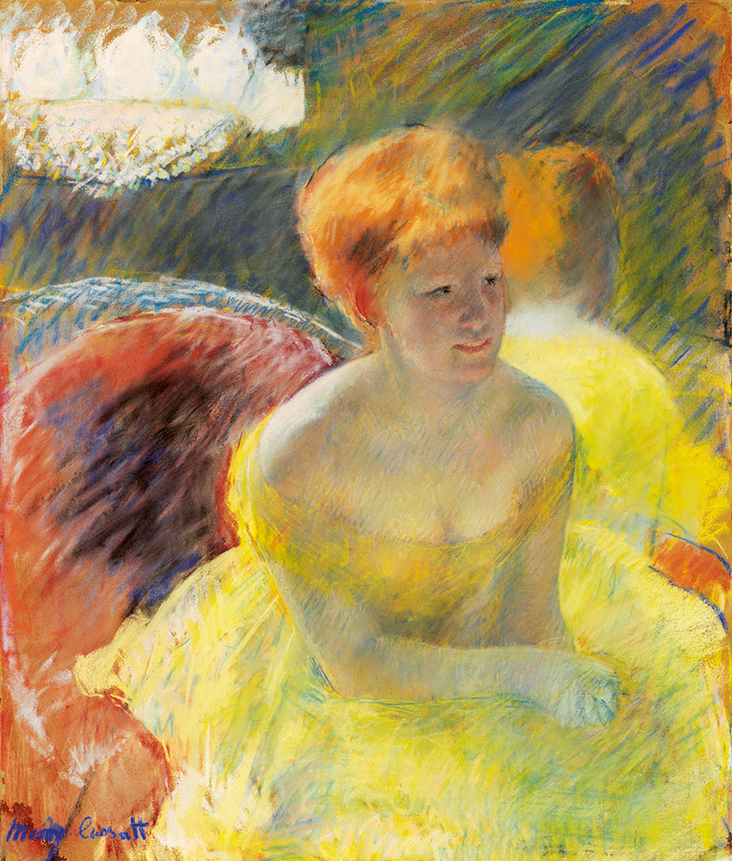

Cassatt was an astute observer of social divisions between men and women, exposing the complexities of gender relations at the time in many of her paintings. In the Loge, 1878 observes a young woman watching the opera while a man in the distance ogles her from afar, and we too become uncomfortable voyeurs, a reminder of John Berger’s famous commentary made nearly 100 years later in Ways of Seeing, 1972, “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves.” Like Degas, Cassatt was fond of making pastel sketches of dancers; in her study At the Theatre, 1879 a young woman is tense with anticipation, an apt metaphor for the performance women were expected to play out on a daily basis. Pollock describes Cassatt’s observations of Parisian society as “extraordinary spectacles where women become part of the spectacle.”

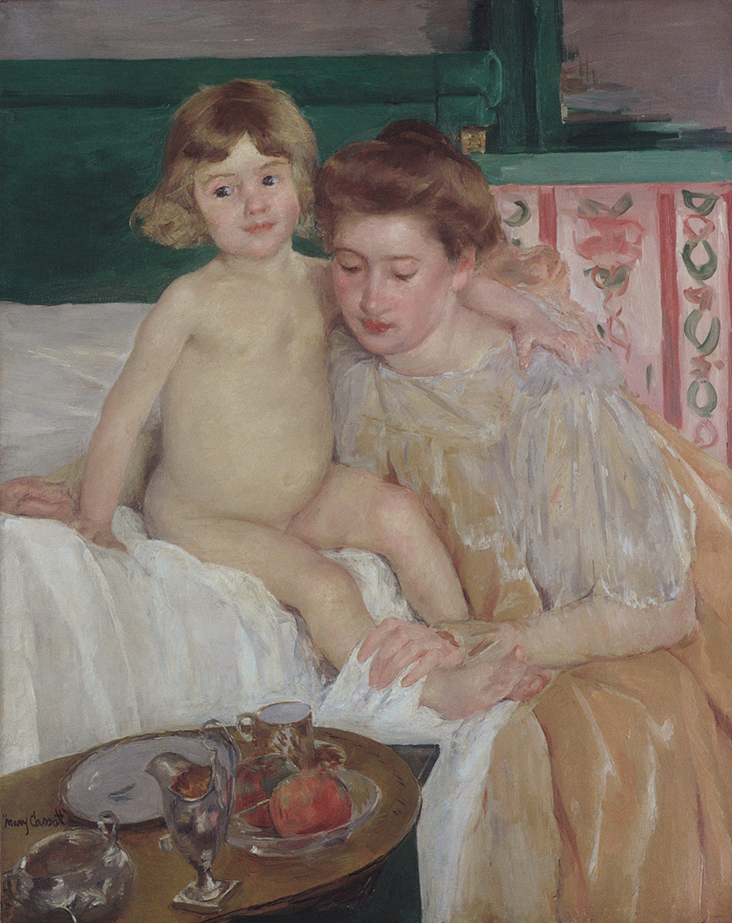

Cassatt focussed predominantly on interior scenes throughout the 1870s and 80s, while popularity in her work grew and she began achieving secure financial independence. When her mother, father and sister all moved to France to live with her in 1877 she had a willing group of sitters to paint, and domestic scenes came to the fore. Though she did not marry or have children herself, she never seemed to tire of painting the subtle interactions between women and young people, including Mother about to wash her Sleepy Child, 1890, Woman Sitting with a Child in her Arms, 1890 and Baby on Mother’s Arm, 1890-1. Where male Impressionists also captured such intimiste, ordinary scenes, for women at the time this was a terrain they were forced to know inside out, giving them a far greater understanding of the emotional tensions within in the arena, as curator Kimberley A Jones points out, “Men were always interlopers in that sphere because they had the rest of the world to roam. The fact that (Cassatt) was a woman gave her an understanding of a sphere that was her natural domain.”

In her paintings of women and children Cassatt was keen to observe the dynamic between figures of different generations. In some, a responsible grown up attempts to cajole a restless, bored young child into towing the line when they just want to roam free, hinting at a dormant, child-like spirit within the women themselves. Others illustrate moments of real tenderness, as children touch their guardian’s faces with curious love and fascination. Much like the Realist paintings of Jules Bastiene Lepage or James Guthrie, Cassatt’s children are often on the brink of self-awareness, drawing us in to their thoughtful inner world with pensive, dreamy expressions.

In her portraits of women Cassatt portrays lively, intelligent and animated figures, sometimes caught unaware amidst conversation, as seen in Young Women Picking Fruit, 1891, on which Pollock writes, “Cassatt’s the absolute master (or mistress) of complex relationships articulated through expressions, through gestures, through space.” She also painted women not blankly staring into space but involved in intellectual pursuits, as seen in Portrait of a Lady, 1878, where the artist’s mother is engrossed in a copy of Le Figaro. Such images encapsulated a rising interest in the concept of the “new woman” that was popular at the time and which the self-sufficient, unmarried Cassatt embodied herself.

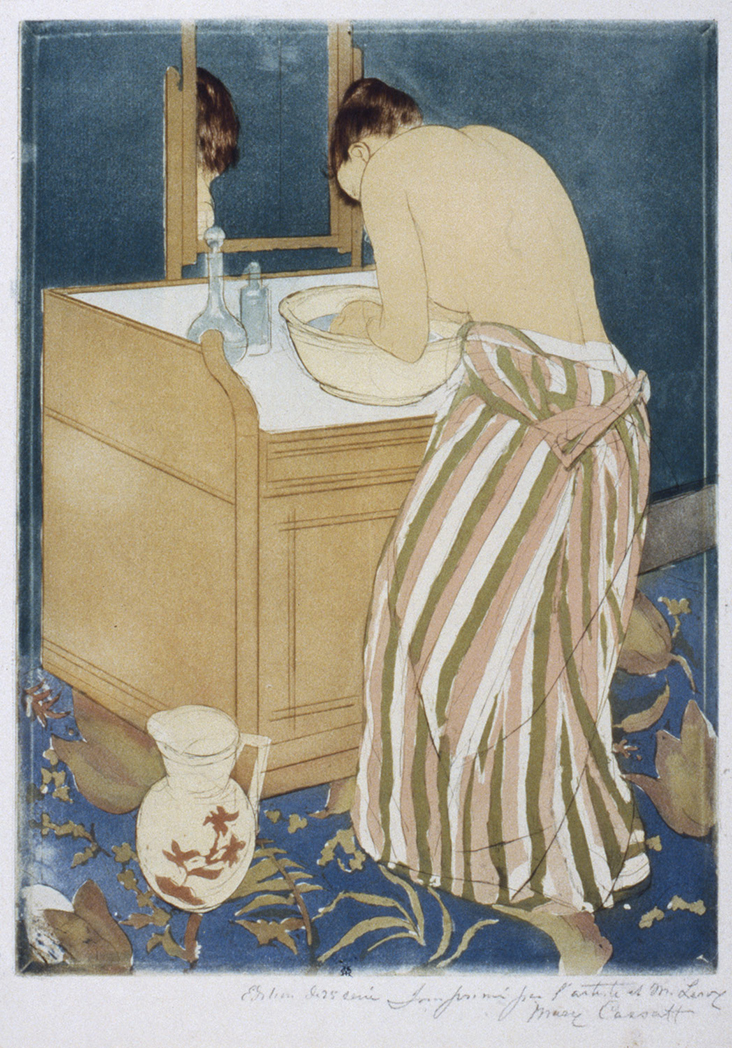

In the following years, Cassatt picked up on the rising trend for Japonisme, creating a series of exquisitely detailed drypoint and etching prints including La Toilette, 1890-1, so popular that Degas revealed his latent sexism, exclaiming with indignation, “I don’t believe a woman could draw that well. Did you really do this?” Cassatt’s biographer Adelyn D Breeskin referred to these prints as, “her most original contribution… adding a new chapter to the history of graphic arts … technically, as colour prints they have never been surpassed.”

Cassatt was commissioned to create a huge mural scaled painting for the Woman’s Building at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, for which she was asked to capture the essence of the “modern woman”. Her career was flourishing in Europe as Impressionist ideas finally took hold – having such a prominent female artist at the helm of this project was an attempt to raise awareness of women’s rising power of at the dawn of a new century. For the commission Cassatt chose to paint a triptych, with the central panel depicting Young Women Plucking the Fruits of Knowledge or Science, the left Young Girls Pursuing Fame and on the right Arts, Music and Dancing. It was a powerful series of motifs giving generations of young women the hope that they could chase their dreams. When Cassatt’s American friend asked her why she chose not to include men in her mural she replied, “Men, I have no doubt, are painted in all their vigour on the walls of the other buildings.”

In the early 20th century Cassatt was awarded a Legion d’honneur by France for her artistic contributions and she took on a powerful advisory role, aiding American collectors and art museums with the acquisition of Impressionist paintings. In her later years Cassatt’s failing eyesight left her unable to make work, yet she continued to exhibit her earlier paintings around the world up to her death in 1926.

Though the times Cassatt lived and worked in were increasingly liberating for women, history has been unkind to her legacy, side-lining her vital contribution to the Impressionist oeuvre in favour of the work by her male colleagues, or belittling her as a painter of sentimental subjects. Writer Lara Marlowe points out the odds that were stacked against her: “Cassatt had three strikes against her: her gender, her foreignness and her reputation as the painter of motherhood.” In the United States her reputation as one of the world’s leading Impressionists was cemented decades ago, but surprisingly, in France, where she spent much of her adult life, her legacy has only begun to take hold in recent years. Looking back, her work gives much needed credos to the vital roles women played in 19th century Paris, portraying them as intelligent, articulate and thoughtful. Such depictions of women have influenced countless artists since, including the deeply personal, feminine languages of Paula Rego and Frida Kahlo. Through her strength of character she was also a great influencer, leading by example a path towards intellectual freedom, arguing for her resolutely feminine voice to be heard: “In art what we want is the certainty that one spark of original genius shall not be extinguished.”

7 Comments

Ann Conyngham

Thank you so much for these inspiring articles!

Victory Mccollough

Another fine article, thank you. Mary Cassat’s paintings of mother and child are so refreshingly sweet.

Vicki Lang

thank you for another wonderful article of the earlier artists. It’s great to know more about their lives and what made them be artists in the first place.

Sarah Dombrowsky

Brava, Ms. Lesso! Another really interesting article. Happy Independence Day.

Cherry Delaney

I had always assumed Mary was French. This was a lovely glimpse into her life and art. Thank you

Sarah Ritter

Thank you for this! I really appreciate your skilled analysis of an under appreciated great.

Nancy Stockman

Another great article. Thank you!