Louise Bourgeois: Fear, Trauma and Catharsis

“I have been to hell and back, and let me tell you it was wonderful.”

Throughout her 70 year career Louise Bourgeois made art as a catharsis, expressing her most intimate fears and anxieties. Though deeply personal, her frank, open language has a universal quality, explaining why she has become such a world renowned artist today. Rising to prominence in the 1950s, she is widely recognised for her empowering female voice, documenting the conflicts of being an artist, mother and wife with brutal honesty, writing “An artist can show things that other people are terrified of expressing.” Her practice encompassed almost any material she could get her hands on, including sculpture, printmaking, drawing and hand-stitching, invested with a gritty, hand-made quality that connects with the human need for touch and intimacy.

Bourgeois was born on Christmas day in Paris in 1911, the second of three children to parents who ran an antique tapestry gallery. When the war broke out the artist’s father was drafted and her mother frantically tried to cope, though Bourgeois remembered these years as fraught with tension and worry as her Uncle was killed and her father was injured. In one of her earliest memories she recalls seeing “…whole trains filled with wounded men with their arms and legs gone.” After the end of the war the family set up home in Choisy-le-Roi, just outside Paris, where her parents set up a tapestry restoration business, often asking the young Bourgeois to help with stitching repairs and re-drawing sections of design. She later remembered, “I became an expert at drawing legs and feet… That is how my art started.”

As a young girl Bourgeois was extremely close to her mother, yet she despised her father for his controlling temper and ritual “humiliating” teasing at family events. When Bourgeois’ mother caught a severe case of influenza and was bed ridden for months Bourgeois dutifully took care of her, while she witnessed her father having several affairs, including a longstanding one with her live-in governess. She never fully forgave him, harbouring deep seated rage, jealousy and a fear of abandonment which would play out in her art as an adult.

In the early 1930s Bourgeois studied maths and philosophy at the Sorbonne for 2 years. When her beloved mother died in 1932 she was devastated and attempted suicide by throwing herself into a river, before being saved by her father. Though she switched to the study of art, her stubborn father refused to offer financial support, believing artists to be “wastrels”, but the canny young Bourgeois managed to arrange free tuition by taking up a role as a translator for American students. Between 1934 and 1938 she studied fine art in various art schools including the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, the Academie Ranson, the Academie Julian and the Academir de la Grande-Chaumiere.

On graduating Bourgeois set up a commercial gallery space selling Surrealist artist prints and paintings next to her father’s tapestry studio, which he chose to support given its commercial leanings. But when the art critic and historian Robert Goldwater came in to buy several Picasso prints he and Bourgeois immediately hit it off, as she described, “In between talks about surrealism and the latest trends, we got married.” Together they moved to New York in 1938, just before the outbreak of the Second World War.

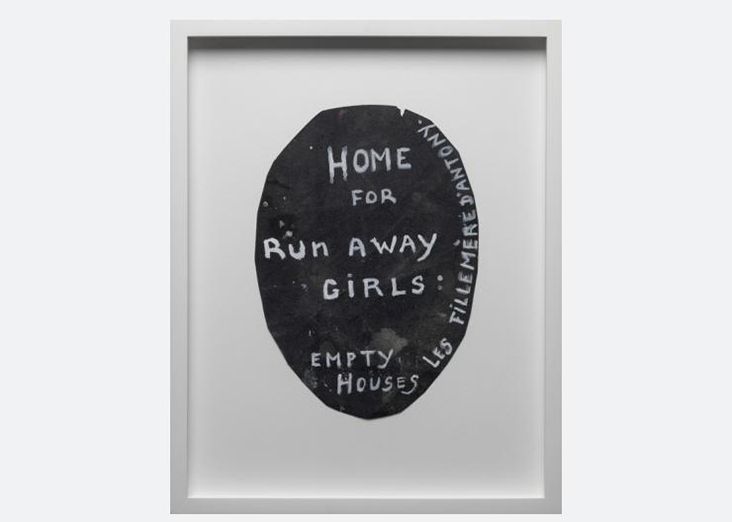

Bourgeois found leaving everything she knew behind for a new life liberating, yet also deeply unsettling, writing, “I was in effect a runaway girl. I was a runaway girl who turned out alright.” This subject of loss, abandonment and transition recurred in various motifs throughout her career, including the early painting Runaway Girl, 1938 and later in the work Home for Runaway Girls, 1994, which was painted onto sandpaper, referencing the grit and determination of young girls that is so often undermined. Calling herself a ‘girl’, even as an adult, was part of her attempt to reject of the shackles and constraints of domesticity.

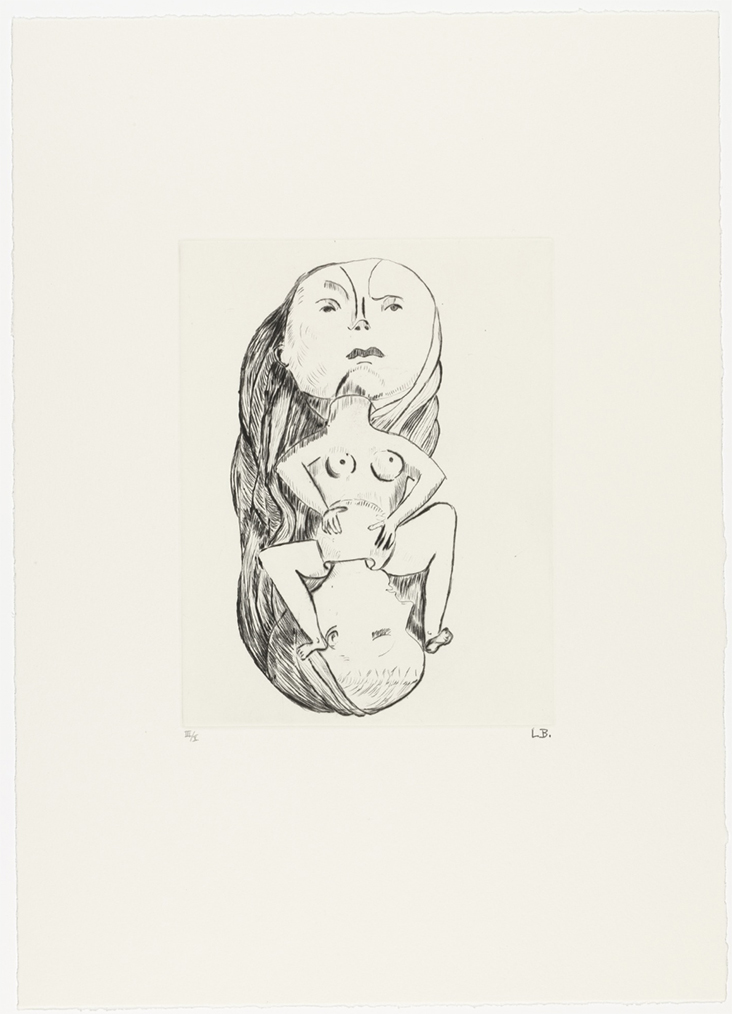

In New York Bourgeois enrolled at the Art Students League, where she focussed predominantly on painting and printmaking. Bourgeois was also keen to start a family – with Goldwater she adopted a French boy in 1940 named Michel, before giving birth to two sons in the next two years, Jean-Louis and Alain. With three young children so close in age to care for Bourgeois struggled to sustain her art practice for the next few years, but by the mid-1940s various autobiographical works on paper appeared portraying a sense of claustrophobia as a woman is tightly contained within a tiny house. Much later she revisited the physical transformations into motherhood through various red gouache paintings including The Birth, 2007.

Bourgeois gradually began exhibiting this new work in various group and solo shows, mostly showing drawings and paintings with expressive, autobiographical content, such as the blood red Natural History, 1944, a reference to female fertility. Her famous spider motif also first appeared during this time in a series of ink and charcoal drawings, which would reappear decades later as giant steel and bronze sculptures.

At the end of the decade Bourgeois began making her first sculptures on the roof of her New York apartment from found scraps of wood and metal. Tall, abstract columns resembling giant clothes pegs or totem poles were described as “a recreation of people I missed … even though the shapes are abstract they represent people.” Against the odds she wrote of a burning, increasing necessity to make, particularly in three dimensions: “I need to make things. The physical interaction with the materials has a curative effect. I need the physical acting out, I need to have these objects in relation to my body.”

A series of solo shows in New York followed, while in 1951 the Museum of Modern Art bought her Sleeping Figure, 1951. Like Bourgeois, various Surrealist artists had relocated to New York after the outbreak of war, who were beginning to explore macho, bravado forms of expressionism. Bourgeois was influenced by the distorted and subconscious language of Surrealism, but she rebelled against this male-dominant genre which often objectified women, as her friend and assistant Jerry Gorovoy points out, “She thought … that the Surrealists made women the object of their work, whereas she was trying to make women the subject.” Breaking apart from the mainstream didn’t come easy for Bourgeois however – it would take several decades before she achieved real recognition. Her deeply autobiographical art often reflected on feelings of alienation and exclusion, both a French woman in America and a woman in a male-dominated industry.

During the early 1950s Bourgeois returned to Paris with her family for several years. Though their relationship had been fraught with difficulties, she was distraught when her father died in 1952, falling into a deep, inconsolable depression. Searching for relief she began what would become a 30 year on-off period of psychoanalysis, often attending up to four times a week during difficult phases. Her copious writings and recordings document a tumultuous journey through therapy and the fears she unearthed. In one haunting excerpt she writes a list of endless worries, “I am afraid of silence / I am afraid of the dark / I am afraid to fall down / I am afraid of insomnia / I am afraid of emptiness…” while another reveals the pressures she felt from the relationships around her, “to be abandoned / to be criticised / to be attached / to be asked too much / used / to be refused…”

By 1955 the family had returned to New York, where Bourgeois was granted American citizenship, though still beset with grief she entered a period of relative seclusion for the next few years, rarely exhibiting her work. When she began exhibiting again in the 1960s the work she revealed was an extension of her psychoanalysis, addressing many of the inner demons she continued to battle with through the depiction of tormented figures or broken forms. Anxiety plagued her as she developed agoraphobia and insomnia, sometimes staying awake for four nights in a row, by which point she had become hysterical and volatile. Gorovsky points out the cathartic affect her art had on ailing her troubles: “If she worked, she was OK. If she didn’t, she became anxious… and when she was anxious she would attack. She would smash things, destroy her work.”

Being a member of the American Abstract Artists Group also influenced the nature of her work as she shifted from upright, rigid forms to sexualised motifs resembling both male and female genitalia suggesting growth and germination. Made from softer, more human materials including latex, plaster and rubber, she described them as neither male nor female, but “pre-gender.” These forms were later reproduced in marble and bronze as Bourgeois spent time in Italy learning new casting techniques, producing iconic sculptures including Janus Fleuri, 1968.

In 1973 Bourgeois’ husband died, sending her into a further period of melancholy and self-analysis. Emerging from the darkness, she produced The Destruction of the Father, 1974, a searing Freudian analysis of her anger towards her father, in which she deconstructs his body into monstrous fragments laid across a bed, referencing the way he betrayed his wife in her own home. As a widow in her later years Bourgeois became a hugely respected and influential figure, both through regular teaching work and her frequent, notorious Sunday gatherings, which she called “Sunday Bloody Sundays”, where artists, students, writers and curators would flock to her home in Chelsea to have their work brutally critiqued by this queen-like figure, often leading to arguments and tears.

Her place in art history was cemented when she became the first woman to be granted a solo exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1982. Major public art commissions followed including her world renowned spider sculptures, made in memory of the artist’s mother for her meticulous weaving skills and her strength of character, as Bourgeois explains, “The spider – why the spider? Because my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat, and as useful as a spider.” Fabric, stitching and weaving also took on physical form in Bourgeois’ later work as she assembled both figurative and abstract works from her vast archive of collected household scraps, transforming the everyday into the mystical an otherworldly.

There is a greater sense of calm in many of the artist’s final works on paper, such as 10 am is When you Come to Me, 2006, a tribute to her long term friendship with Gorovoy and I Give Everything Away, 2010, in which she seems to have surrendered and finally laid her personal demons to rest, inscribing in the last work of the series, “I am packing my bags.”

Since her death in 2010 at the age of 98, Bourgeois’ legacy has remained buoyant as she continues to exert a powerful and lasting influence on contemporary art. Her home in New York has now become the Easton Foundation, dedicated to preserving her vital legacy for generations to come. Feminist artists Lynda Benglis and Judy Chicago were empowered to carry on her subversions of female stereotypes, while it seems hard to imagine Tracey Emin and Sarah Lucas’ probing self-analysis without her influence. “I am my work, I am not what I am as a person,” reflected Bourgeois, revealing just how tightly interwoven she was with her tenacious, self-reflective practice.

Feature Image: Le Lit, Gros Édredon, Bleu / Louise Bourgeois / 1997

2 Comments

Jan Stutsman

Very interesting. Thank you!

Heather Barclay Davis

Wonderful!!! Thank you!