Tamara de Lempicka: Power and Decadence

Artist Matches Model To Painting, Tamara de Lempicka (Baroness Kuffner) and Miss Cecelia Meyers with the painting Suzanne au Bain / May 14, 1940 / Beverly Hills, CA

“I live life in the margins of society, and the rules of normal society don’t apply to those who live on the fringe.”

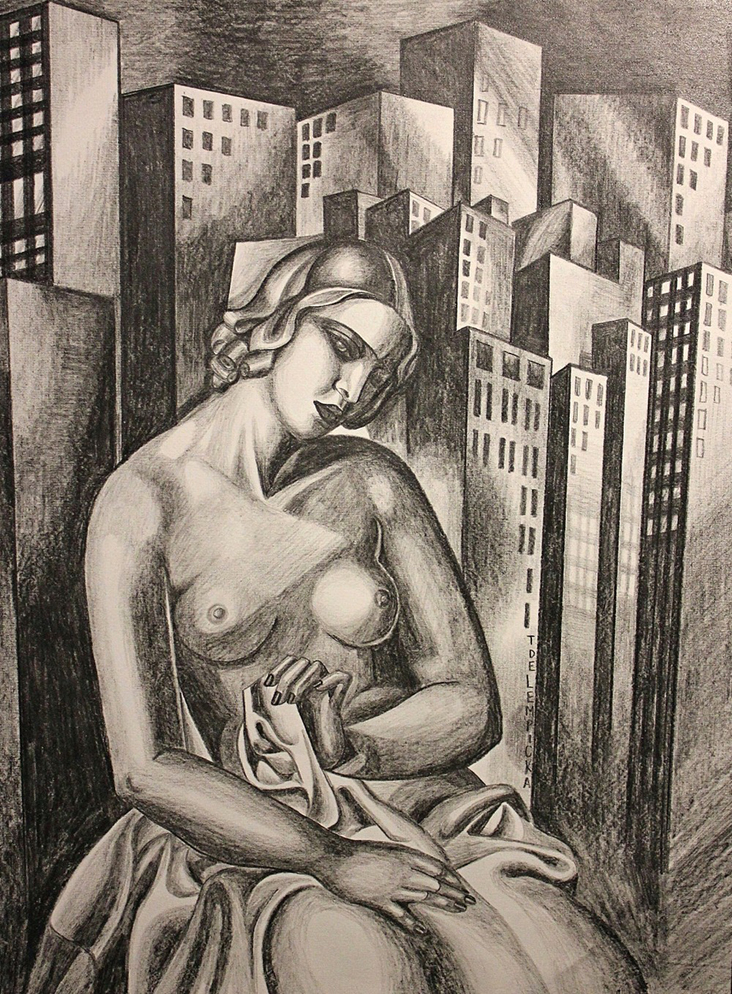

In Tamara de Lempicka’s world women are fierce, independent and effortlessly stylish. Today her highly collectable paintings are potent symbols of a bygone era, capturing the sensuous glamour and decadence of the 1920s with coral lipped beauties set against stylised Modernist backdrops. She was a radical proto-feminist, upending the classical representation of women as demure and passive, painting women from a female perspective as powerful figures in charge of their own bodies and minds. Her style was as radical as its content, combining elements of Art Deco with Cubism and Futurism, making her a hugely influential trailblazer. She wrote, “I was the first woman to paint cleanly, and that was the basis of my success.”

Born Maria Gorska in Warsaw, Poland to a wealthy family, the young artist had a colourful upbringing that came to inform her future art. She attended boarding school in Switzerland and spent summers with her grandmother in Italy, where she first encountered the art of the Italian Renaissance, falling in love with their luminous colours and fleshy bodies. She wrote, “I discovered Italy when I was a youngster and my grandmother took me away from the cold climate of Poland, where I was born and lived, to take me to the sunny cities of Florence, Rome, Naples, Venice and Milan. It was under her attentive guidance that my eyes took in the treasures of the Italian Old Masters, from the Quattrocento, the Renaissance.”

When her parents divorced in 1912 she was sent to live in St Petersburg with her wealthy aunt, who encouraged her to attend social events in Russia’s high society. At 15 the confident, tenacious young artist met and fell for the lawyer Tadeusz Lempicki, marrying him three years later. Tadeusz was arrested in 1917 when the Russian Revolution broke out, and imprisoned in an unknown location, but Lempicka hunted him down and was successful in demanding his release.

The couple soon left Russia for Paris to begin a new life, where the artist first adopted the name Tamara de Lempicka. Despite her wealthy ancestry Lempicka’s refugee status in Paris left her with little money, while her husband struggled to find a secure job. They lived off the sales of family jewellery for a while until funds ran out and Lempicka was forced to find another source of income, spurred on by the birth of her daughter Kizette in 1919. Initially she took on several commissions to paint portraits of her neighbours, before enrolling at the Academie de la Grande Chaumiere to study painting. There she learned from the Nabis painter Maurice Denis how to paint figures with a graphic, “soft Cubism”, developing a signature style early on which would inform her art for the rest of her career.

On graduating Lempicka soon established herself in Paris’ vibrant, lively art scene which was thriving during the “roaring twenties.” She was hugely prolific and held a series of solo exhibitions, as well as establishing a steady stream of portrait commissions from members of Paris’ high society. Lempicka’s distinctive merging of eroticised Italian Renaissance figures with elements of Art Deco geometry, Cubism and Futurism proved immensely popular, as she wrote, “My goal: never copy. Create a new style, with luminous and brilliant colours, rediscover the elegance of my models.” She reflected on the glossy machine age that was rising around her, so full of excitement and promise in the postwar era, situating figures alongside shiny cars, glistening buildings and slick, polished advertisements, as seen in her empowered Portrait of the Duchess of La Salle, 1925. Many of her paintings were also infused the glamour of Hollywood’s golden age, with figures dressed in indulgent fabrics and set amidst dramatically lit scenes, such as Irene and her Sister, 1925. These images were particularly appealing to Paris’ fashion market; in 1925 her stylish paintings caught the eye of various fashion magazines including Harper’s Bazaar, who helped publicise her work and promote her career.

As her painting career expanded Lempicka became a sexually liberated bohemian, having scandalous affairs with various men and women, particularly those whose portraits she painted. She was particularly drawn to Paris’ lesbian and bisexual “women only” artist and writer groups, where she befriended influential figures including Vita Sackville West and Natalie Barney, while her paintings reflected her attraction to the female body as a symbol of power and sexual freedom, as seen in Group of Four Nudes, 1925 and her Nude on a Terrace, 1925. Her nudes nod towards the Italian Renaissance with statuesque, sculptural female forms, but they have a far greater sense of autonomy. Art Historian Joan Cox argues that Lempicka created these images as, and for, a female voyeur, writing, “(Lempicka) has chosen to crop her view of the female bathers tightly and give the viewer – a presumably female viewer – the experience of joining in the frolicking. She invites the female viewer in as a lover rather than creating an experience for a male viewer as a distant voyeur into this all female public space.”

Such a raucous lifestyle inevitably led to the breakdown of her marriage in the following years, but professionally she was just getting started. At the Exposition Internationale des Beaux-Arts she received first prize for the striking portrait of her daughter, Kizette on the Balcony, 1927. Two years later she was commissioned by the German fashion magazine Die Dame to create a cover image that celebrated the rising independence of women, for which she produced the iconic and much loved Self Portrait in the Green Bugatti, 1929. The work depicts Lempicka as a sophisticated symbol of strong femininity at the wheel of a Bugatti race car, wearing an elegant leather helmet and gloves while a luxurious silk scarf encircles her suggesting freedom and movement. The image catapulted her into the artistic spotlight and became an enduring symbol of its time, prompting The New York Times to christen her the “steely-eyed goddess of the machine age.”

In the late 1920s Lempicka began an illicit affair with married art collector Baron Raoul Kuffner, who she eventually married in 1934 when his wife passed away, leading the press to lend her another moniker as the “Baroness with a brush.” Her career continued to flourish, even throughout the Great Depression, as she took on ever more prestigious clients, famously painting King Alfonso XIII of Spain and Queen Elizabeth of Greece. In the same year her work was exhibited in the United States for the first time at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburg, to great acclaim.

After the outbreak of war Lempicka moved with her husband to Los Angeles, where they set up a new home in the former house of the famous film director King Vidor. Lempicka found some success through painting the Hollywood celebrities that had fascinated her throughout the 1920s, as well as producing a series of angular and suggestive still life studies, although the popularity of her work was beginning to wane. Critics have commented that the overtly glamorous decadence of her art no longer seemed fitting after the war, when a more sombre mood had taken over, a change of pace that the hedonistic socialite struggled to adapt to. In 1943 the pair moved to New York, where they continued to socialise with the wealthy elite, but her career as an artist took a backseat.

Lempicka’s husband passed away in 1961, and she ignited her adventurous spirit once again by taking on three round the world voyages by ship, followed by a move to Texas, and later Mexico in her final decades. Lempicka tried her hand at abstraction during this time but with little success. However, there was a rising interest in her earlier work by now, as various exhibitions were staged to celebrate the Art Deco era she had encapsulated with such powerful and celebratory motifs, images that provided a visual counterpart to the much loved literary world of F Scott Fitzgerland.

After her death in 1980, interest in Lempicka’s practice has been on the ascent, while recent auction prices for her art have soared into the millions as various museums and wealthy celebrities have amassed collections of her paintings. She is recognised today as a pioneer of her era alongside her contemporaries Coco Chanel and Simone de Beauvoir, redefining the role of women in society, through both her own grit and determination and the towering symbols of modern femininity celebrated in her art. Her ability to seamlessly blend lifestyle with art has influenced generations of artists in various industries – it is telling that Madonna and Barbara Streisand are amongst her greatest collectors. Contemporary photographers Steven Meisel, Karl Lagerfield and Eugenio Recuenco have since paid homage to Lempicka by imitating her distinctive, striking sense of drama in many of their photo-shoots, recreating the strength and power she gave to her figures. As the driving force behind her own fortune, Lempicka famously wrote, “There are no miracles, there is only what you make.”

2 Comments

Tricia Landis

I love your blog articles, I hadn’t heard of this artist. The posts where you feature a piece of art and a piece of linen coordinating color are also great, they feed my imagination! Thank you!

Susan Johnson

Yes! new to me, and inspired. great pieces. many thanks!