Georgia O’Keeffe: The Call of the Wild

“I’ve always been absolutely terrified every single moment of my life … and I’ve never let it stop me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.”

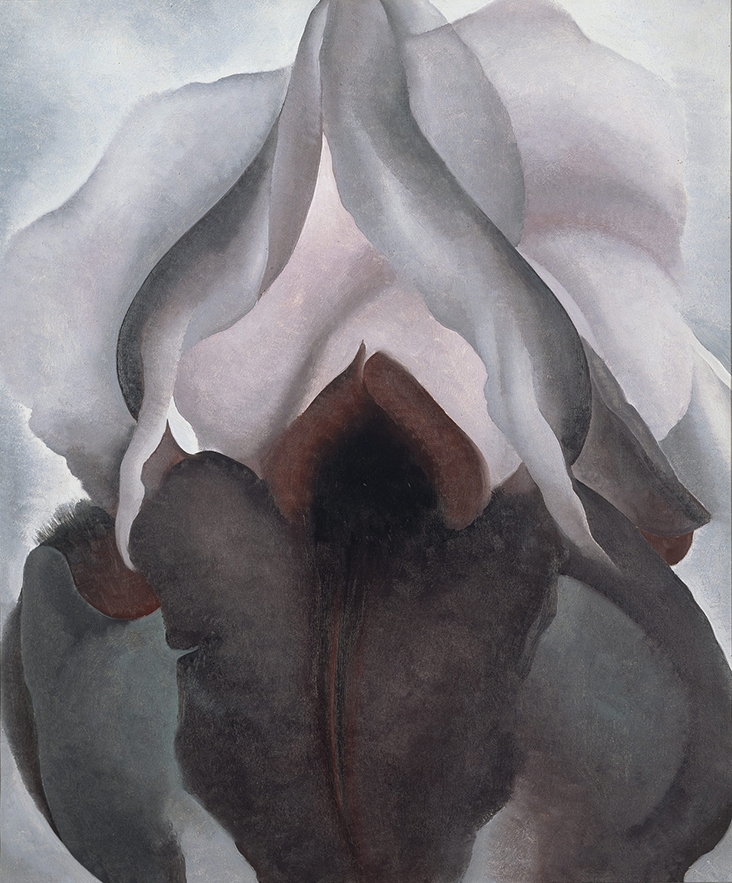

Fleshy, voluminous flowers that spread open like wings or petals that curl into tendrils of fire: these are the images that made Georgia O’Keeffe an icon of American art. But in a career that spanned more than seven decades O’Keeffe’s oeuvre was hugely varied, ranging from wild flowers, barren deserts, dry bones and vast cloud filled skies to looming skyscrapers, all seen through her sleek, minimalist eye. Beneath the art, O’Keeffe was a quietly tenacious character, waiting in the darkness for the sun to rise, painting with her feet and climbing onto rooftops to get closer to the stars. Hers was a prolific, endlessly inventive career that earned her the title: “Mother of American Modernism.”

Born and raised as part of a large family on a farm in Wisconsin, O’Keeffe’s untameable surroundings were an ongoing source of fascination. As an adult she remembered, “Where I come from, the earth means everything.” The artist’s mother was determined and intellectual, encouraging her daughter to aim high; when the young Georgia expressed an interest in the arts her mother swiftly arranged Saturday painting lessons with a local watercolour artist.

During her studies at the Art Institute of Chicago from 1905-6 O’Keeffe was ranked top of her class, but her early success was cut short when she contracted a life threatening case of typhoid fever. After taking time off to recover O’Keeffe moved to New York to study with the art students’ league, where she learned traditional realist painting and how to place an emphasis on composition and design.

By 1907 O’Keeffe’s mother had fallen ill and her father had filed for bankruptcy, leaving them unable to fund her art studies. Instead she moved back to Chicago, finding work as a commercial artist, drawing lace and embroidery for advertisements. It was a high pressure, fast-paced industry which she found deeply competitive, and after two years she had left. O’Keeffe took on various teaching roles in the following years, including a stint at a school in Amarillo in Texas, where she found she could lose herself in the wilderness, with its extreme weather patterns, forceful winds and gushing, relentless streams.

In the following years she gradually began to make art again, with distant visions of becoming an artist in New York. In a letter to a friend she wrote, “If I went to New York I would be lucky if I could make a living.” At a summer school in Virginia she learned about the precision and elegance of Japanese art, with its close, cropped compositions and lush, floral patterns. An artistic breakthrough came in 1915 with a series of pioneering charcoal drawings that delved into the unchartered realms of abstraction, with organic forms that swoop across the picture plane, echoing the free flowing movements of nature. Initially O’Keeffe sent these drawings to her friend Anita Pollitzer in New York, who in turn showed them to photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz.

He was so taken with these drawings he put them on display in his established New York gallery. When O’Keeffe visited him unannounced, Steiglitz developed an infatuation, writing to her in 1917, “How I wanted to photograph you – the hands – the mouth – and eyes – and the enveloped in black body – the touch of white – and the throat – but I didn’t want to break into your time.” He was 52 and an established figure in the New York art scene when they met, while she was 28, an unknown. Their correspondence would span over 25,000 letters over the course of their courtship and marriage.

In the years that followed O’Keeffe developed into a successful, financially independent artist, yet she was well aware of her position as a woman in a man’s world, often having to defend her status as an artist, not a ‘woman artist’. Writer Olivia Laing wrote of this internal struggle she faced: “How do you make the most of what’s inside you, your talents and desires, when they slam up against you a wall of prejudice, of limiting beliefs about what a woman must be and an artist can do? She didn’t kick the wall down – hardly her style – but instead set her considerable canniness and will at prising a new way through.”

Stieglitz encouraged critics to read overtly sexual, Freudian meaning into her richly coloured, exotic floral paintings, but O’Keeffe categorically denied such readings, publicly defying her husband’s interpretations by claiming them for herself as a celebration of nature and perception. She wrote, “I know I cannot paint a flower. I cannot paint the sun on the desert on a bright summer morning but maybe in terms of paint colour I can convey to you my experience of the flower or the experience that makes the flower of significance to me at that particular time.”

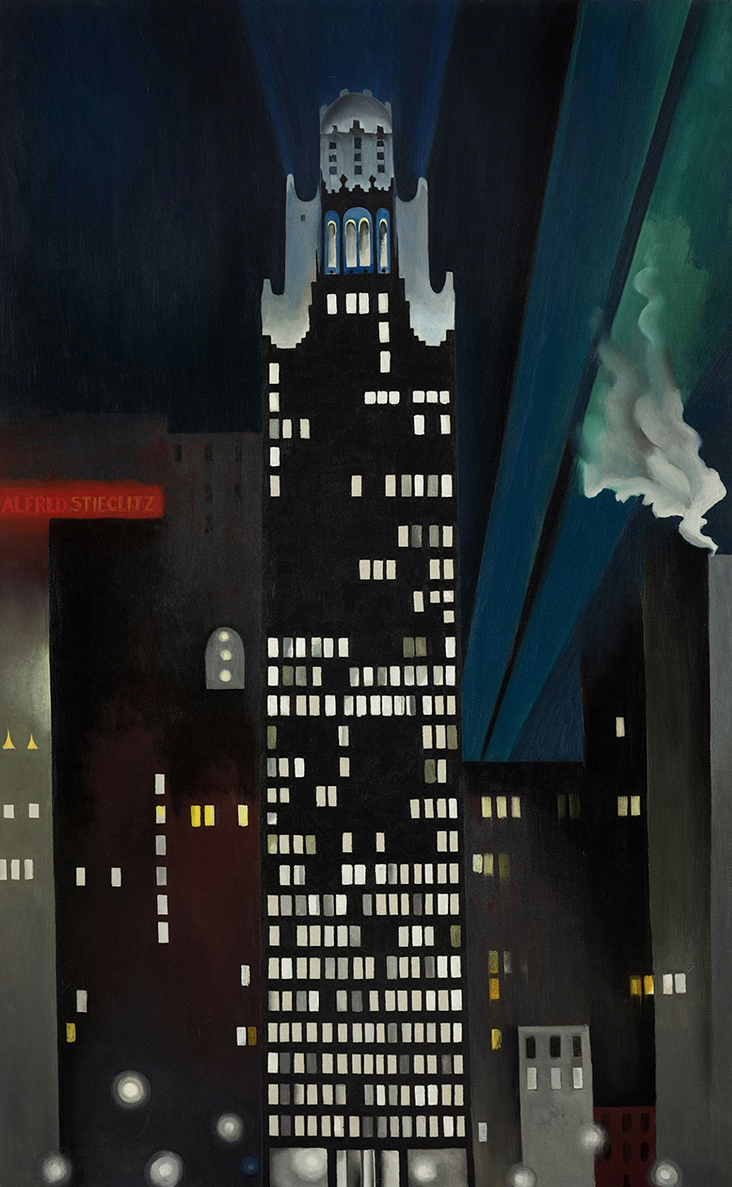

When O’Keeffe and Stieglitz moved into an apartment on the 30th floor of the Shelton Hotel her worked changed track; she was dazzled by towering skyscrapers that punctured the night sky with patterned grids of speckled light and soon began painting them in rich, blue and black toned art deco style paintings, producing iconic mementoes of New York in its 1920s heyday. She said, “I know it’s unusual for an artist to want to work way up near the roof of a big hotel, in the heart of a roaring city, but I think that’s just what the artist of today needs as stimulus … Today the city is something bigger, grander, more complex than ever before in history.”

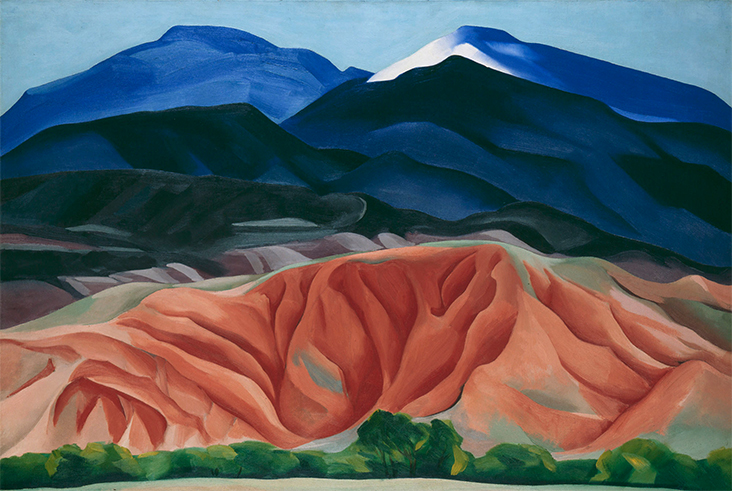

By 1929, in a quest for greater autonomy from her life with Stieglitz O’Keeffe went to stay with the arts patron Mabel Dodge Luhan in New Mexico, a place that would come to have a career defining impact on her practice. After two months, she wrote to Stieglitz, “There is much life in me – when it was always checked in moving towards you – I realised it would die if it could not move towards something … I chose coming away because here at least I feel good – and it makes me feel I am growing very tall and straight inside – and very still – Maybe you will not love me for it – but for me it seems to be the best thing I can do for you – I hope this letter carries no hurt to you – it is the last thing I want to do in the world.”

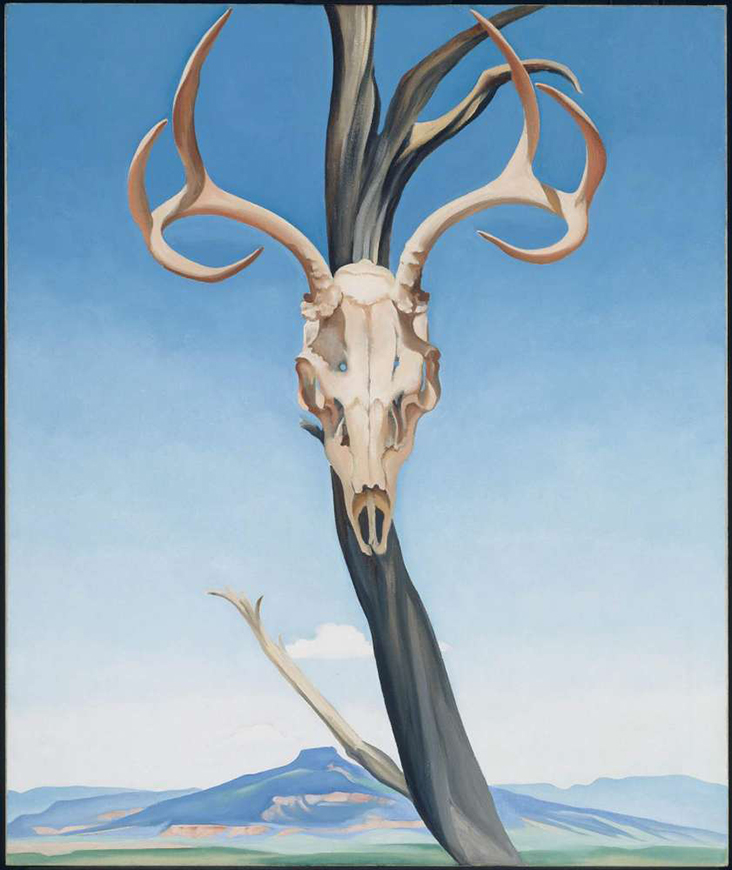

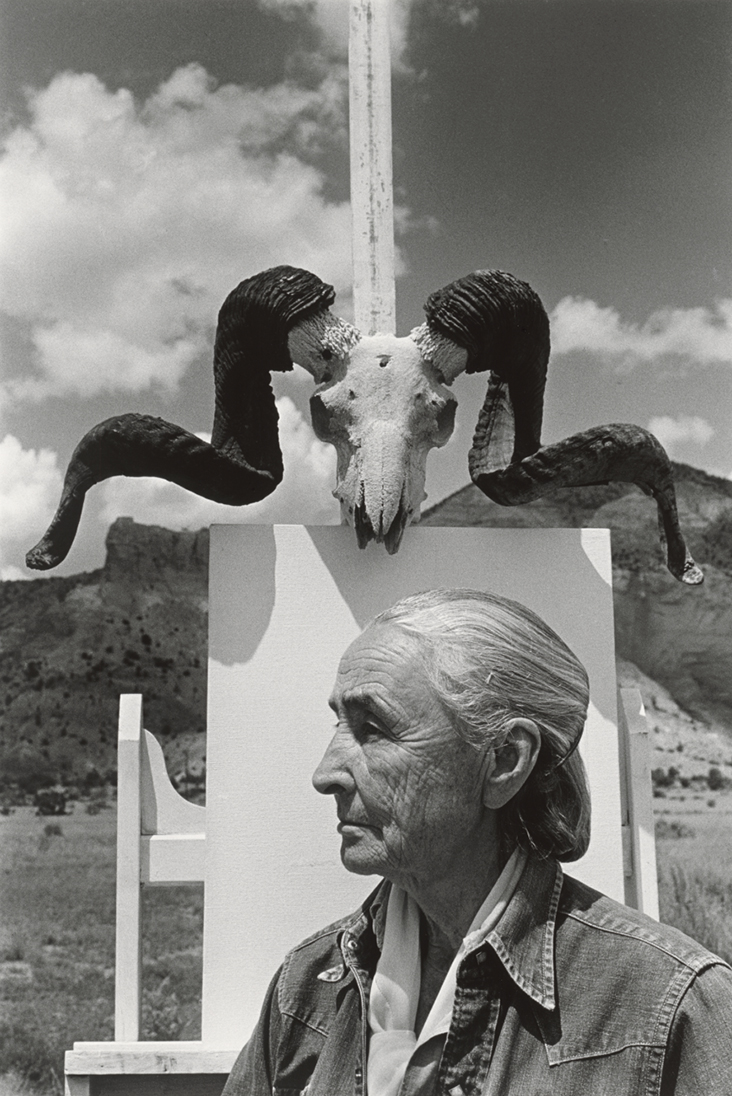

In New Mexico she was entranced by the wide open skies and broad vistas of barren land that seemed to go on into infinity. Over the next 20 years she spent large parts of her time living and working there, painting expanses of desert and dry, dusty bones with muted sandy tones against vivid blue skies, finding new depths of artistic freedom in the wilderness. Her evocative paintings came to influence a generation of artists in New York, who went in search of the same rustic, wild side of America untouched by industrialisation.

O’Keeffe’s legacy was cemented with several major retrospectives, one in 1943 at the Art Institute of Chicago and the second in 1946 at the Museum of Modern Art. When Stieglitz passed away in 1949 O’Keeffe made a permanent retreat to New Mexico, where she remained for the rest of her career, exploring her own artistic voice away from the bustle of the city with a dogged determination. She said, “I have but one desire as a painter – that is to paint what I see, as I see it, in my own way, without regard for the desires or taste of the professional dealer or the professional collector. I attribute what little success I have to this fact. I wouldn’t turn out stuff for order, and I couldn’t. It would stifle any creative ability I possess.”

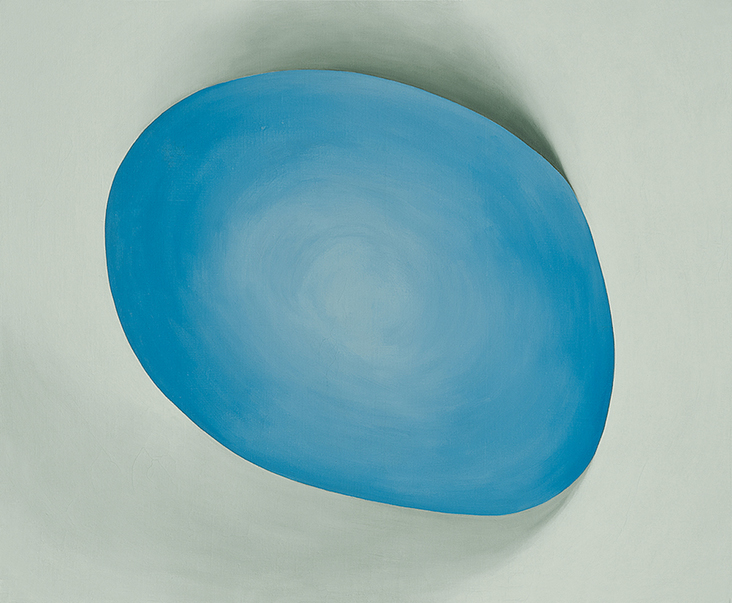

She spent the 1950s travelling internationally, creating paintings depicting the awe and wonder of the natural world through sublime vistas, famously capturing the mountain peaks of Peru and Japan’s Mount Fuji. Ever the master of reinvention, in her 70s she began a new, elegant series of minimal clouds and sky that seem to open out into endless space. Despite suffering macular degeneration in her later years, O’Keeffe continued to paint with the help of studio assistants, stating, “I can see what I want to paint. The thing that makes you want to create is still there.”

Although O’Keeffe’s work fell out of fashion during the 1960s, throughout the 1970s her work experienced a new spike in interest with the rise of feminism, as female artists including Judy Chicago and Miriam Schapiro celebrated and reinvigorated her fierce independence through their own writing and art. O’Keeffe was a member of the Pro-Suffrage Women’s Party, but in 1976 she refused to give her work to an all-woman exhibition in Los Angeles titled Women Artists: 1550 to 1950, saying “I am not a woman painter! (I am) one of the best painters”, period. This status rings true today; her work at auction achieves some of the highest ranking prices for any modern artist, with one of her paintings sold for 44.4 million in 2014. Her legacy lives on through the Georgia O’Keefe Museum in Santa Fe, with its pioneering research centre for supporting the next generation of contemporary artists. She was a driven, passionate visionary, whose words encapsulate her wild, creative spirit: “(Painting is) like a thread that runs through all the reasons for all the other things that make one’s life.”

4 Comments

Susan Johnson

Rosie Lesso’s art commentaries are a wonderful find. I have been an artist my whole life.. I rarely sell.., though I continue to create and be inspired at 74. Thank you, Rosie, for the richness your pieces add to the fabric of my art life.

Rosie Lesso

Thank you all for taking the time to read and comment on the articles!

Jan Bennett-collier

I did not experience much art training in my education over 60 years ago, so I greatly appreciate Ms. Lesso’s articles on art and color on this site. She seems a very knowledgable young woman who is also very interested in the why of these artists. Her articles have been enjoyable and I’m pleased each time I see another of her perspectives posted. The help me learn something new that day. Thank you, Rosie Lesso!

Jan Bennett-Collier

Mary Berdan

Bravo to Rosie Lesso! I have formal art training and didn’t learn as much as I have from Rosie’s articles. I too look forward to her posts. Plus, my friends into art enjoy her articles also as I post them on Facebook.