Raoul Dufy: Still Waters Run Deep

There is a sparkling lightness of touch associated with Raoul Dufy’s practice, one that defines the joi de vivre of the Parisian Belle Epoque era he was raised in. One of his most popular quotations, “my eyes were made to erase all that is ugly,” reveals his inclination towards the decorative and beautiful, or the lighter side of life, from the glittering water of the Le Havre shorelines to the Regattas, horse racing and outdoor leisure pursuits of the wealthy Parisian elite, captured with bold designs and swift brushstrokes. Yet beneath the apparent spontaneous self-confidence of his artworks are hidden depths of self-reflection, hesitation and doubt, driven by an enquiring mind that was ready to shift styles, mediums and even industries, spanning painting, tapestry, textiles, set designs, stationary and ceramics. Although better known as a Fauvist painter, one of his strongest, yet underrated legacies is his contribution to the textile industry; as the first artist of the 20th century to become successfully involved in commercial textiles he produced over 5,000 different designs, revealing the depth and variety of his creative prowess.

Dufy was born to a middle class family in Le Havre and grew up in a simple household as one of nine children, watching from a distance the impossibly rich elite on their yachts and in high society races, a subject he would return to again and again throughout his career. With Dufy’s parents struggling to feed so many children, he was forced to leave school at the age of 14 to earn money for his family, instilling in him a work ethic that would stay for life. The first job he gained was at a coffee importing firm as a junior clerk, where he experienced his first taste of the exotic as the shipments arrived from far flung places, bringing new, potent aromas.

Watching the rippling water reflecting the light, Dufy felt a desire to start drawing the boats in the harbour, saying, “I revelled in the light peculiar to estuaries …radiant until about the 20th of August, from then on it grows more and more silvery.” A year later he had enrolled in evening art classes, where he met his lifelong friend Emile Othon Friesz. With what little money they had the pair established a studio space together, sharing mutual interests in the light and expression of Impressionist painting. In 1900 Dufy received a paid scholarship to study fine art in Paris at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. Yet despite high hopes, he struggled with the traditional teaching methods and his professor, the painter Leon Bonnat, was deeply critical of his vivid colours. He remembered, “I had nothing to hope for at the Ecole.” Art historian Albert Skira later wrote, “Dufy took a sceptical attitude, expressing the view that the true artist always works outside the pale of the official organisations …. In the teeth of their opposition…” From this vanguard position Dufy continued to pursue brightly coloured Impressionist painting after graduating, living and working in Paris with his fellow artist friends through abject poverty, even having to skip meals to keep painting.

Dufy’s paintings changed track in 1905 when he encountered Fauvism for the first time, experiencing the true spirit of the avant-garde in their vivid, exaggerated colours and crude, expressive marks and he soon began to emulate their style. The paintings reflected the spirit of the times, with artists growing increasingly frustrated with the historical traditions of painting and shaking up the old system. With the surge in industry and technology came a population rise and Paris was one of the first cities in Europe to be redesigned into a new city for a new age in the late 19th century. As an antidote to the corruption of industry, the Fauves looked back to a simpler way of life, examining the rich artefacts being imported from the Orient and Africa to Europe, objects that represented a simpler time when art, and society, was more in tune with human nature. Such objects also challenged the notion that art should come from direct observation, and showed little division between the fine and decorative arts.

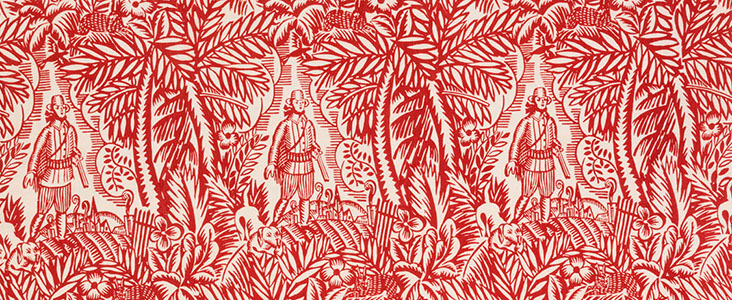

Moroccan textiles, African carvings and Japanese prints all flooded into the imagery of French artists and designers, reshaping a new visual culture where divides between the fine and applied arts were being gradually broken down. Woodcut printing was revived as a modern technique, with its possibilities for creating crude, immediate designs in an array of colours, and Dufy soon adopted the technique for himself. With a newly designed Paris also came a wealthy class of prosperous urban dwellers who divulged in urban leisure pursuits beyond the walls of the city, including tennis, swimming and rowing, subjects which often featured in Dufy’s Fauvist paintings, along with his woodcut designs of decorative, flowing motifs from nature including flowers, plants and animals.

Despite being hugely prolific in painting and printing, Dufy was still desperately struggling to earn a living. He turned his hand to commercial illustrative work, designing a series of woodblock prints featuring animals for the writer Guillaume Apollinaire in 1909. His striking designs caught the eye of the renowned fashion designer Paul Poiret, known in Parisian circles for his generous, collaborative spirit, and for placing his dresses on the same level as works of art, famously writing in his memoir, “Am I a fool when I dream of putting art into my dresses, a fool when I say dressmaking is an art? For I have always loved painters, and felt on an equal footing with them. It seems to be that we practice the same craft, and that they are my fellow workers.” As an art collector and amateur artist, Poiret was always on the lookout for new talent. He commissioned Dufy to produce woodblock printed stationary designs for his interior design workshop, Atelier Martine, and was so impressed he began regularly hiring Dufy to create hand-printed fabrics for his dress designs.

With Poiret’s financial backing Dufy established La Petite Usine (The Little Factory), in 1911, a workshop space for creating hand printed fabrics to be used in Poiret’s dresses. Together the pair shared an affinity for African and Oriental art and Poiret’s extensive art collection had a marked influence on Dufy’s designs, ranging from big, bold florals to small intricate patterns, printed in simple, select bright colours. When realised as Poiret’s dress designs, Dufy saw the energy of his artworks coming to life as wearable works of art, saying, “Paintings have spilled from their frames and stained our dress and our walls.”

Poiret had developed a reputation for creating loose, clean shapes, based on designs by the young, untrained assistants he hired, and these became the perfect backdrop to showcase Dufy’s fabric, seen in La Perse, and the Bois de Boulogne; with their eye-popping, bold designs and free flowing shapes they dazzled a public more accustomed to soft paisley prints and corsetry. Their designs were an instant success and the following year Dufy was asked by the textile manufacturer Bianchini-Férier to produce printing plates for furniture and dress fabrics. The fruitful collaboration would last over 16 years, with Dufy producing thousands of hugely popular designs.

Dufy returned to painting in the 1920s, as well as expanding into ceramics and set design. He continued to develop his visual repertoire, exploring a light, airy handwriting that would come to bring further recognition and success, culminating in the huge scale murals at Paris World’s Fair in 1937, illustrating the story of The Electric Fairy with translucent layers of colour and light. In 1946, writer Gertrude Stein reflected back on his lifelong legacy, saying, “One must meditate about pleasure. Raoul Dufy is pleasure.”

Dufy’s interdisciplinary approach was hugely influential on the next generation in Britain, on the Continent and in America and many artists subsequently developed design strands to their practice. After the two World Wars, some of the world’s leading artists explored textiles including John Piper, Salvador Dali, Ben Nicolson and Pablo Picasso, a trend that would continue to rise with Pop art in the 1960s. But Dufy was quite unique in his determination to master both fields, questioning the very role of art and what it can do, an attitude that can be felt in the work of many artists and designers today. Contemporary examples include the wearable art of designers Alexander McQueen and Christian Lacroix, where garments compete for attention with their models through outlandish shapes and prints, as well as designer Yiqing Yin, who drew on Poiret and Dufy’s “childish sense of life and freedom” for Shinsegae International’s Autumn/ Winter 2018 collection.

Throughout the later 20th century Dufy’s art fell out of favour, but in recent decades major galleries around the world have aimed to restore his legacy, revealing the extent of his prolific output and the quiet determination that drove him to keep pushing forward into new, unchartered territory. The late, contemporary curator Bryan Robertson summed up his legacy with great pathos, “I believe that Dufy … works harder at …applied art than any other serious painter in our century and his achievement in the field of decorative art can only be described as monumental.”

2 Comments

A L

With respect for your wonderful article, you have a serious typo, Dufy worked in the 20th C (1900s) not the 19th C (1800s)

Rosie Lesso

Ok, thanks for the tip – that should be it changed now!