Innovation and Collaboration: When Art Becomes Fashion

In this new series, we will explore three revolutionary artists who have crossed over from the art world into textiles and fashion, delving into the obstacles they faced and what led them to pursue commercial ventures.

Art and fashion: two distinct industries, yet their divide is more porous today than ever. Many of today’s contemporary artists regularly leap over into the realms of fashion design, with recent collaborations including Damien Hirst and Alexander McQueen’s macabre skull and butterfly print scarves, Tracey Emin’s woven bag designs for Longchamp, Takashi Murakami’s longstanding relationship with Marc Jacobs and Jeff Koons’ Masters series with Nicolas Ghesquiere for Louis Vuitton. Rebellious, innovative makers in both fields continue to work together in new ways, treating fashion as an art form for everyday life. In the age of mass communication and advanced technology, the cross fertilisation of innovative ideas that transcend disciplines is becoming increasingly commonplace, with artists and designers finding ever more inventive ways to share ideas.

Such freedom of expression was not always possible, but has been evolving gradually over the past 100 years or so, along with dramatic advances in technology, industry, society, science and communication. At the turn of the 20th century a period of social and technological upheaval was taking place; the international Industrial Revolution had swept across Europe and the United States, leading to the development of new, large scale machines, steam power and huge factories for increased manufacture. Textiles became one of the most dominant industries to increase in growth, branching out from cottage industry into mass scale production throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Cities across Europe were bursting with a population surge and the machine age became the perfect chance to create a sleek new living environment, one that rejected the Victorian past and celebrated the future. One of the first cities to be redesigned was Paris, which subsequently became the art capital of the world throughout the 20th century, attracting creative voices from many different countries. The city’s most adventurous and experimental artists and designers seized the opportunity to incite a change in traditional, Victorian culture, design and art history, leading to the dawn of avant-garde movements including Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, Cubism, Futurism and Orphism, movements which first began to break down the traditional barriers between art and design.

Both Raoul Dufy and Sonia Delaunay were trained in Paris during this time, experiencing the social upheavals and shifts in modern art that were taking place around them, each integrating themselves in bohemian, Parisian art circles. The progressive, left-wing bohemian culture that arose was radical and out of sync with the majority of conservative Parisian society, placing them in the position of émigré or outsider, struggling against public ridicule.

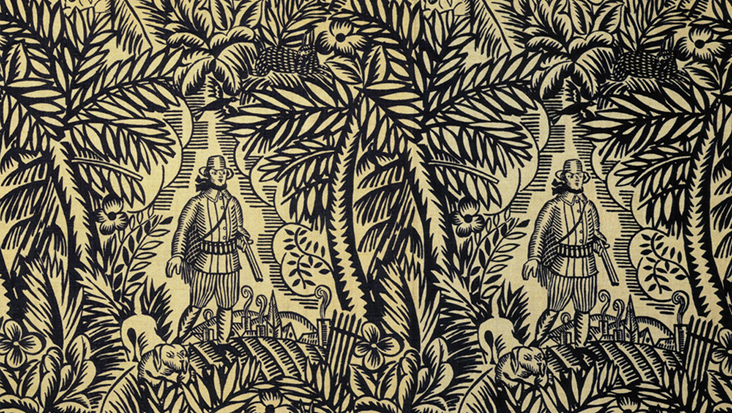

La Chasse, furnishing fabric, woodblock-printed linen and cotton. Designed by Raoul Dufy for Bianchini Ferier, Lyons, 1920

Dufy began his career as a Fauvist painter, rejecting the traditional form of painting with perspective, depth and space in favour of simplified, flattened landscape and plant forms painted with crude, expressive brushstrokes, celebrating the vibrancy and joy of life. When exhibiting his Fauvist paintings for the first time in 1906, they were harshly criticised by the press and public for their childlike simplicity, yet Dufy held on to his belief for a decorative art that could “erase all that is ugly.” In 1909, with his painting career floundering, Dufy began a collaboration with the great fashion couturier Paul Poiret, initially designing stationary and later printed textiles for his fashion house, a partnership which would eventually ignite commercial success. Poiret confessed his ongoing love affair with artists, saying, “I have always loved painters, and felt on an equal footing with them. It seems to me that we practice the same craft, and that they are my fellow workers.”

Sonia Delaunay’s career also grew out of early 20th century Paris. Initially born in Ukraine as Sarah Elievna Stern to a poor Jewish family, she later moved to St Petersburg where she was adopted by her mother’s wealthy brother, taking the name Sonia Terk. Yet her Jewish roots would stay with her, particularly a belief that needlework ranked on the same level as painting. After studying art in Germany, she moved to Paris, coming into contact with the leading avant-garde styles including Post-Impressionism, Cubism and Fauvism. In 1909 she met and married fellow artist Robert Delaunay, changing her name to Sonia Delaunay, describing her husband as, “a poet who wrote not with words but with colours.”

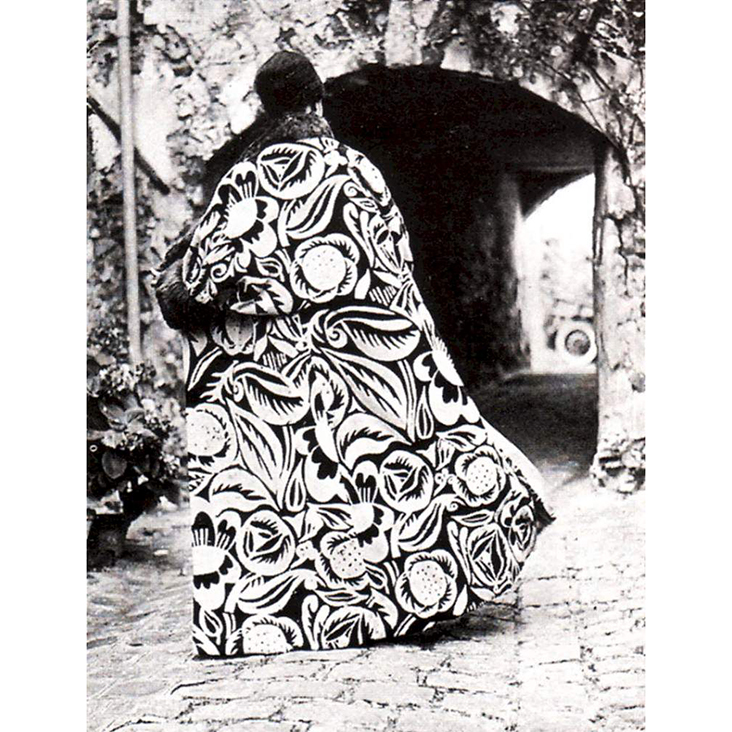

The design strand of Sonia Delaunay’s career began when she made a crib blanket for her son, inspired by the patchwork quilts of Ukranian peasants, with geometric patterns resembling Cubist paintings. This period marked a turning point, when she first began to explore design simultaneisme, or vivid colours placed together to create rhythm and movement, a style which became known as Orphism. After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Sonia Delaunay’s financial support from her family was cut. Forced to consider an alternative income she launched into couture design, establishing the brand Simultane, producing geometric textiles that were transformed into clothing, fabric coverings and interior décor; hers was a truly living art.

In Germany, one of the major 20th century avant-garde movements to arise was the Bauhaus, a style that revolved around the forward looking art school of the same name. Originally founded by Walter Gropius in 1919, the Bauhaus movement levelled the field between fine arts and crafts, encompassing graphics, architecture, paintings, interiors and weaving. With a Marxist philosophy Gropius declared, “Let us create a new guild of craftsmen, without the class distinctions that raise an arrogant barrier between craftsman and artist.” Uniting all these ideas was a belief in the unifying power of geometry, an attempt to instil some order against the backdrop of political chaos and destruction after the First World War.

Despite its supposedly progressive outlook, when the ambitious young art student Annelise Else Frieda, known as Anni, entered the Bauhaus, hoping to train in fine art, like other female students she was discouraged from entering the painting school and instead steered towards the weaving workshops. With an entrepreneurial, inventive spirit she made the best of her situation, elevating the ancient craft of weaving and its associations with domesticity to the status of modern abstract art, soaking up influences from leading abstract painters including Paul Klee and her future husband Josef Albers, changing her name to Anni Albers, infusing her artworks with intricate patterns and designs that today rival the paintings of her male contemporaries.

Anni Albers, Thickly Settled, 1957, cotton, jute, 31 × 24 3?8″ © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/DACS, London/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Each of these artists broke new ground through their rebellious, forward thinking practices, leading the way for countless contemporary artists and designers today. Dufy radically influenced the popular arts and commercial design of the following decades, particularly the lush, leafy designs of Art Deco, while his open, collaborative approach with Paul Poiret revealed new ways of working together towards a greater whole. Delaunay’s original approach to colour, form and rhythm combined utopian ideals with vibrant, decorative designs and her emphasis on liberating women through wearable, living art still resonates with artists and designers today. Anni Albers ripped up traditional divisions between applied and fine arts, transforming the status of weaving into a true art form and the fashion world still remains indebted to her rich, densely worked geometric designs, with designer Paul Smith saying, “The rest of us are still trying to catch up.”

Join us again in the next articles when we will look more closely at the lives of these visionary artists, examining the personal and political struggles they faced during their rise to prominence and success.

6 Comments

Patricia Dudley

Thank you so much for writing well on this wonderful subject! I look forward to your future articles.

Patricia Dubois Dudley

Rosie Lesso

That’s great, I’m glad you enjoyed reading it!

Margaret Ryan

I really enjoyed this article. I find it disturbing, though, that these women are introduced and referred to only by their husbands’s last names–even before they are married. Are their birth names available? Shouldn’t we use them? Thanks.

Margaret

Mary Brinner

I had the same thought while reading this very interesting article.

Rosie Lesso

Hi Margaret, thanks for the feedback and that is a good point! I have edited the text accordingly. I will be going into the biographies of these women’s lives in more detail in the following articles, so this is really just a short introduction to explain how important they were. I’m glad you enjoyed reading it!

Cindy Fisher

I really enjoyed this article, as Raoul Dufy has always been one of my favorite artists. Thank you!