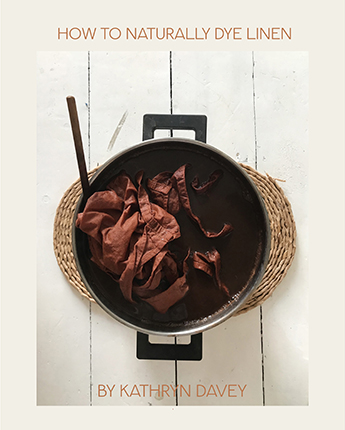

Pioneers of Modernist Architecture, Part One: Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier

The first of our Modernist heroes’ are three men who at the beginning of the twentieth century were sailing into the future creating a new landscape within architecture and design. They were reinventing what architecture should stand for, they were trialling new materials, and questioning how function should dictate design and aesthetic. In this article we will take a glimpse at three of these influential architects: Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier.

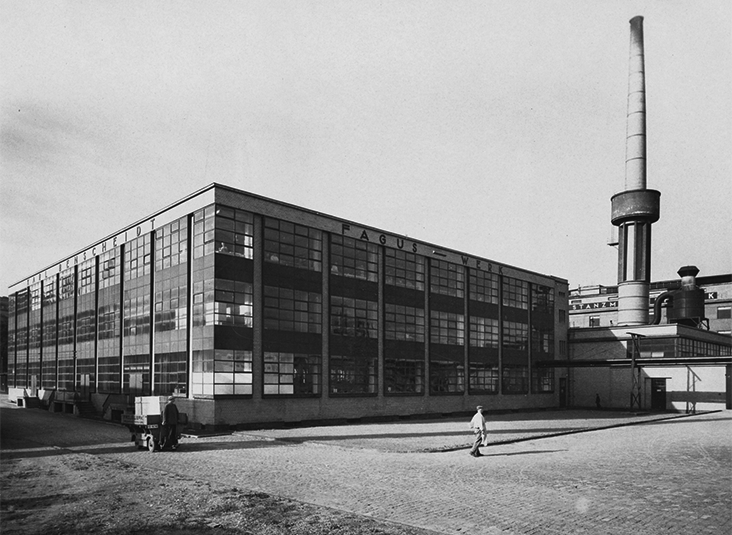

In 1938, construction of a family home began just outside of Boston, Massachusetts, for a new professor at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Vastly different from the typical Colonial Revival regularly seen in Boston surrounds, it featured glass block, acoustic plaster and chrome details then unseen in local architecture.’ The stylish home belonged to Walter Gropius, the German born architect and former director of the Bauhaus Design School. A son and a nephew of architects, Gropius studied architecture before joining Peter Behrens’ architectural firm in 1908 where he worked along side Ludwig Mies Van der Rohe. One of Gropius’ first and most outstanding buildings was the Fagus-werk. The factory, which produced wooden ‘lasts’ for the manufacturing of boots, was in the process of ambitious expansion under a different architect yet Gropius was able to convince the owner of Fagus-werk’ Carl Benscheidt that his vision was exactly what Bernscheid was looking for. In April 1911 Gropius gave a lecture which would lay the foundation for his design of Fagus Factory. “In his lecture, “˜Monumental Art and Industrial Construction’, he explained that train stations, departments stores, and factories should no longer be built like those from previous decades and needed to evolve to suit changing societal and cultural dynamics. Gropius emphasized the social aspect to architectural design, suggesting that improving working conditions through increased daylight, fresh air, and hygiene would lead to a greater satisfaction of workers, and therefore, increase overall production.”‘ The most innovative feature of the building is the fully glazed exterior corners, which are free of structural elements.

In 1919, Gropius served as the headmaster of the Grand-Ducal Saxon School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar eventually transforming it into the Bauhaus. His aim for the Bauhaus was to educate artists, designers, and architects to observe the world through their knowledge and imagination and reflect it in their work. He desired that all artistic disciplines, whether a painted canvas or a house, be brought together as a unified whole. He believed whether artist or craftsman- all deserved equal appreciation and should unite around the same goal in architecture thus creating harmonious construction. With the rise of the Third Reich pressure was brought to bear on the Bauhaus forcing it to move from Weimar to Dessau into the now iconic building designed by Gropius in 1930. It was just a few years later in 1936 that Gropius left his homeland and emigrated to the United States.

For Ludwig Mies van der Rohe architectural design came naturally. His lack of formal training caused no barrier for his structural genius and modern point of view. Like Gropius, he became a leading German architect, building the iconic Barcelona Pavilion for the German section of the World Exhibition in Barcelona and several acclaimed residences, including Villa Tugendhat, in Brno, Czech Republic while still in his twenties. Before Gropius left Germany, he asked his innovative colleague to become the new director of the Bauhaus in 1930. Sadly, the persistent intrusion of Nazi power forced the closure of the Bauhaus in 1933.

Mies arrived in the United States in 1938 and was selected to be director of the Department of Architecture at Armour Institute in Chicago. Mies’ philosophy ‘less is more’ can be traced throughout his architecture’ design aesthetic with’ clean lines and open spaces.’ Mies believed that the internal bones of a building were as beautiful as the external’ façade thus purposefully exposing the often unseen components of structural engineering. One of his greatest accomplishments was designing the Illinois Institute of Technology campus. The campus’s design featured gleaming glass and steel buildings, curtain windows and brick. His design gave a clear nod to the technological advancements of the time.’ In 1958, he built the Seagram Building in New York City, his first high-rise construction. Many consider his designs the origins of contemporary skyscrapers.

Finally, Charles-Edouard Jeanneret, more famously known as Le Corbusier (a twist on his maternal grandfather’s name), was a Swiss-French architect and prolific writer on the subject who designed his first house at age 20 in 1907. Instructed in visual arts at Arts Décoratifs at La Chaux-de-Fonds, Le Corbusier traveled throughout Europe taking various apprenticeships before landing in Peter Behrens’ architectural firm where he possibly worked along side Gropius and van der Rohe.’ Influenced in part by spatial concepts, geometrical forms, concrete construction, and the role of landscape in architecture, Le Corbusier eventually returned to Switzerland and opened his own firm in 1924.

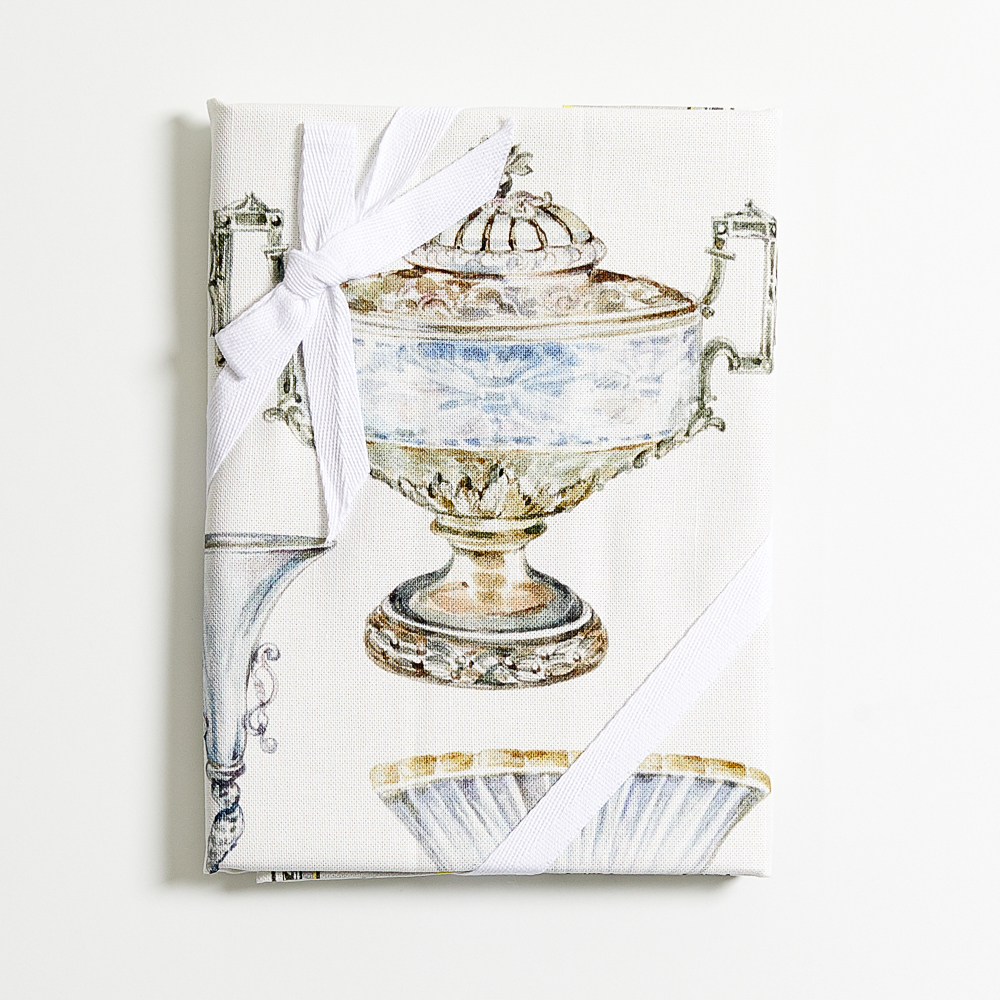

Villa Savoye in Poissy, France

Villa Savoye in Poissy, France

In his work, Vers une architecture (Toward an Architecture) he concluded, “œA house is a machine for living in,” a concise commentary of his design perspective. He believed each structure should include five specific elements. Villa Savoye is perhaps the pièce de résistance in fully endorsing his five points of architecture: an elevated structure supported by pilotis, or columns, usually constructed in concrete, an open floor plan, non-support walls, or free facade, which allows unlimited choice for wall placement, ribbon windows offering natural light and expansive views, and a roof terrace or garden for domestic use.’ Le Corbusier also ventured into furniture design with his cousin Pierre Jeanneret and Charlotte Perriand, creating the LC Collection using chrome tubing, leather and fabric in shapes that mirrored human form.

If you someday find yourself on an architectural tour around the world, you should easily stumble across the timeless works of these visionaries.’ And should you wish to begin with the Gropius House, the address is 68 Baker Bridge Road, Lincoln, Massachusetts. You’re welcome. Be sure to join us for Part Two of The Fathers of Modernist Architecture when we will look at Charles and Ray Eames and Alvar Aalto!

Leave a comment